Report 7: The Temple of Artemis at Sardis (2020)

by Fikret Yegül

Chapter 3. Building History and Chronology

Introduction

Regarding the original design of the Temple of Artemis at Sardis and its successive renovations, Howard Crosby Butler wrote, “we are confronted by a curious combination of certainty and doubt.”1 After five years of excavation and many more of research, Butler was uneasy because the well-preserved plan and the “mass of details” did not seem to add up to a clear design or a construction sequence that represented several distinct historical phases.

A century later (and after further archaeological work), we are in a much better position to understand the architecture and construction of the temple and its wider cultural context. There is, however, much we still do not know. We are still baffled by the unorthodox design of the temple and its complex building history. While the east end of the temple—the east wall with its monumental door, a six-column projecting pronaos porch, and an eight-column east facade—remain nearly intact, the west end is fragmentary and confusing. Three walls—at varying distances from the firmly preserved east wall (including the original west wall, also referred to in this book as the middle crosswall, of the temple)—cross the elongated cella, and the western two show indirect evidence for centrally placed doors. These crosswalls and the two back-to-back platforms for cult images indicate that, at some time in its history, the temple had a two-cella arrangement. However, relative to the overall topography and the great Lydian/Hellenistic altar (LA 1/LA 2), the architectural features and the major level differences evident in the west end are in many aspects unclear, and they require some hypothetical proposals (see Fig. 1.2). With the exception of a few topographical benchmarks, the original landscape around the temple still presents some questions, even if we can predict the nature of the larger features and the extent of the sanctuary.

Except for the southwest corner column (column 64), none of the west peristyle columns of the temple had been started even at the foundations; other columns of the peristyle are preserved unevenly in their foundations or are missing completely. Of the west pronaos porch, at least five of the column foundations including the middle two with pedestals) are preserved at the level of their tops or column base plinths, and they probably carried columns; significant numbers of fluted drums were found in this area, too. Even at the end of its life as a pagan temple sometime in the fourth century AD, the building was largely unfinished. New, intrusive construction inside and around the cella prepared the building for its continued, partial use during the Christian era and later—its afterlife, in current parlance.

A flight of marble steps on the northwest corner is an incongruous element with respect to Greek temple design, especially since these steps are not connected presently to an architecturally defined temple platform or to a stylobate, as a regular crepidoma would be (e.g., the Temple of Apollo at Didyma). In fact, we have no stylobate proper at all. A heavy mass of mortared-rubble construction envelops the temple peristasis. Furthermore, the early monumental altar LA 1 (substantially enlarged at a later date to LA 2), located on the temple axis at the west of the building and probably once physically connected to it, complicates the question of the temple’s orientation and its relationship to the earlier elements of the larger sanctuary of Artemis before the temple proper was built.

As preserved, the temple is categorically a pseudodipteros incorporating spacious amphiprostyle porches within its ends, three intercolumniations deep. We are confident that the cella and its interior columns, and probably the columns between the anta walls at both ends, were the first to be built (but were later removed or incorporated into a new cella configuration). The peristyle belongs to a later—Roman—stage coeval with the division of the cella into two equal-length, back-to-back chambers to house the newly granted Roman imperial cult. The two major, interconnected questions before us are thus:

(1) What are the origins and architectural nature of the pseudodipteral design and its possible predecessors?; and

(2) What is the date and nature of the conversion of the temple into a double-cella structure that responded to the needs of dual cult worship?

And, one might add,

(3) What is the relationship of the temple to Anatolia’s own architect Hermogenes, if any?

These questions, and others related to them, have engaged generations of scholars, who provide differing or overlapping solutions based on their own interpretations of the evidence: archaeology and physical remains, architecture, design and historical precedent, construction and materials, economics, epigraphy, ceramics, coins, and ornamental style—and, of course, the aspects of Sardis’s social and religious culture that affected the use and design of the temple during different periods.

-

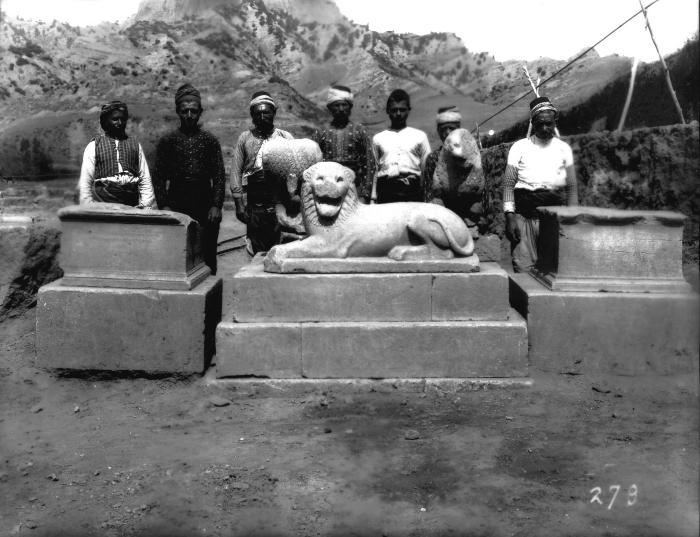

Fig. 1.2

Temple of Artemis, general view, including altar in front, with acropolis and Tmolos Mountains (looking southeast). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

State of the Scholarship

I will present here a summary review of the current state of scholarship on the temple, starting with its original excavator, Howard Crosby Butler. Seeing the building through the eyes of many scholars and following their analyses and proposals, past and present, exposes the many sides of the problem and elucidates their various and sometimes divergent proposals. Many of these, I gratefully acknowledge and accept. Against this backdrop, I present my own interpretations and proposals (often built upon this earlier research and subject to the same historical shortcomings and conflicts) based on the last forty years of close documentation and study of the temple. Where I can offer no consistent and satisfactory explanations, and where I am at variance with other proposals (even some contemporary archaeological ones), I am content with presenting the evidence as I know and understand it, and I defer to the judgment of present and future peers; likewise, I will represent some alternative views but enunciate what theories I prefer and why.

Howard Crosby Butler

According to Butler, there had been an older marble temple, begun in the time of Croesus, whose purple sandstone foundations once emerged just west of the Hellenistic west wall of the temple. In 1960 Gruben identified these blocks (now gone) as the foundations of the stairs and the original west door of the cella (see pp. 52-54). Butler imagined that the course of limestone blocks running across the foundations of column 79 (built over by the late west crosswall and visible on the northern end of its west face) was further evidence for this “older” temple (“probably the relics of this temple”).2 The purple sandstone foundations were instead constructions of the Hellenistic era for the door and its stairs, while the limestone has been shown to belong to the foundations of the Roman west crosswall (see Fig. 3.32).3

Butler’s hypothetical “early” temple, he explains, burned down during the Ionian Revolt of 499 BC and was replaced by an all-marble temple of the Classical era (by which Butler meant the mid-fifth century BC), which in turn was damaged in the fourth century BC. Butler proposed that this second temple was a colossal dipteros planned along the same lines as the Classical Artemision of Ephesus, though never completed. The present (third) temple was, under the Seleucids (perhaps Antiochus I, r. 281–261 BC), in Butler’s view, not an independent building but merely a continuation of its fifth-century BC predecessor; it incorporated many of that structure’s elements, including column foundations and bases, and most of the capitals and fluted columns, especially those raised on pedestal bases in the middle east pronaos porch (columns 11 and 12).

Butler also speculated that the renowned Anatolian architect Hermogenes, who may have been employed at Sardis during the rule of “the great Pergamene building monarch” Eumenes II (197–159 BC), could have been responsible for the temple’s pseudodipteral plan.4 Butler could not substantiate this complex chronological sequence of temples—from Archaic to Roman—with any convincing evidence, such as actual building elements or datable ornament. Nor has any archaeological evidence emerged to support his thesis in the many trenches opened in the temple since his time. Although Butler was wrong in his grand scheme of the temple’s evolution, he was right in some of his piecemeal interpretations of the temple’s past and architectural usage.

According to Butler, work on the peristyle columns was nearly complete when the great earthquake of AD 17 hit Sardis. He thus believed that Roman work on the temple was not a substantial rebuilding (or a “phase” proper) but rather was restricted to repairing, replacing, and strengthening the earthquake-damaged structure, especially the bases and shafts of the east colonnade; the capitals, however, appear to have escaped the destruction and were used for a second, and even a third, time.5

Butler proposed that the fourth-century temple faced east, with the old Archaic altar (LA 1) “at the rear of the temple”—a situation that was seriously and justly questioned by Gottfried Gruben (see below), as it would be by most scholars today.6 Butler argued that the east door, whose finely carved jambs were compared favorably to early Hellenistic ornament from Priene, belonged to the original building (which I now date on stylistic grounds to the Hadrianic period, see pp. 167–174).

Butler also considered what we call the “east crosswall” to be simply a thin, nonstructural screen wall, but still an original, internal feature of the Hellenistic cella. What he thought was the “back wall” of the temple (the Roman “west crosswall”) we now know was the front wall of the west-facing temple. The space between the latter and the west crosswall appeared to him to be an independent room with a pair of interior columns (columns 77 and 78); Butler erroneously dubbed this space the “treasury.” Since the floor level of this room (actually part of the pronaos porch) was some 1.60–1.70 m lower than the cella proper, any connection between the cella and the “treasury” would have required a door and a stair, for which he could find no evidence. He admitted that this was a problem for which he had no solution, but he tentatively restored a pair of doors at the north and south ends of the wall—shown with question marks on his plan—without any stairs.7 However, he correctly identified the weaker rubble-masonry foundations in the middle of the west crosswall as evidence for a central door into the “treasury.” Butler did not realize that the west wall, not bonded to the north and south long walls of the temple, is a late feature, not an original wall. More surprisingly, he did not notice that this wall was laid directly over the foundation blocks of the pair of columns of the west pronaos (columns 79 and 80; see Figs. 2.64, 2.65; Plan 6), directly west of columns 77 and 78. This last oversight may explain his misinterpretation of the temple’s orientation and resulting invention of a “treasury” as a part of the original Hellenistic scheme.

Another problem area for Butler—and still for us, to a certain extent—was the marble steps that lead up to the western end of the temple from the north (“Northwest Stairs”). Believing these to be an original, early aspect of the design, Butler incorporated them into his ingenious, entirely fanciful, and grandly symmetrical restoration that also connects the great altar to the temple’s west front (Fig. 3.1). The magnificent, neo-Baroque design actually works (but cannot be substantiated by evidence) and reveals, perhaps, more about Butler’s own roots in the Beaux-Arts tradition of architecture than what the evidence on the ground supports or how Hellenistic Ionic temples were designed.8

Butler did not wish to attribute an independent building or rebuilding “phase” to the Roman period, except for a strengthening of the foundations by encasing them in rubble construction and “extensive repairs at the eastern end,” necessitated by the earthquake of AD 17. However, the early discovery of the colossal head of the empress Faustina the Elder in the western part of the cella (and several other colossal male and female heads inside of or in proximity to the temple; see p. 198, Table 3.1) allowed him to propose that “the old west wall of the cult-chamber was removed . . . in order to convert the cella into a double sanctuary hall.”9 The deified empress stood on the Roman era concrete base in the new “duplex” cella, facing west, and Artemis, on the other side of the “light dividing wall,” faced east—a theory that was at least partially correct, as far as the conversion of the cella into a “double sanctuary hall” is concerned.

Butler also claimed that the entire cella had been made into a deep cistern after the temple fell into disuse during the Byzantine era. He interpreted the brick-colored mortar in the chamber between the original west wall (middle crosswall) and the west wall as a Byzantine version of opus signinum laid over mortared-rubble construction. Since he removed this layer almost entirely, it is hard for us to evaluate this interpretation, although what little remained in the northwest corner of the original cella (as observed by the author in the early 1990s) appeared no different than typical Roman mortar for floor paving in marble. This is indeed what British Consul George Dennis, who originally exposed that part of the temple in 1882, had thought. A more professional opinion was that of architect Francis Bacon, who was also at Sardis in 1882 and reported in a letter to Charles Eliot Norton: “He [i.e., Dennis] found a terra cotta Roman pavement.”10

George M. A. Hanfmann and Kenneth Frazer

The Harvard-Cornell Expedition, under the supervision of director George M. A. Hanfmann and architect Kenneth Frazer, undertook a partial study of the temple and its precinct between 1960 and 1972. Ten test trenches were opened, in addition to the deep sondage under the original image base, in order to elucidate questions of stratigraphy and dating.11 These excavations provided evidence on the use of the area as a sanctuary sacred to Artemis during the Archaic and early Hellenistic periods—and perhaps at some point in time also to Zeus—but no architectural traces of an earlier structure were found under or around the temple. Hanfmann concluded that, contrary to Butler’s belief, no earlier temple, Archaic or Classical, existed below the present one, whose builders “constructed the piers [and column and wall foundations] directly into torrent deposits” that had washed down from the Acropolis slopes.12

Hanfmann believed that the temple was begun during Seleucid rule (Seleucus I Nicator, r. 301–281 BC), after the Battle of Koroupedion in 281 BC. He thought that at that time it was already conceived as a two-cella temple “with Artemis [facing west] and Zeus [facing east] as protectors of the Necropolis and Acropolis respectively.”13 However, Hanfmann also suggested that the division of the cella actually occurred during the short reign of Achaeus, the rebellious Hellenistic general who ruled Sardis 220–213 BC.14 He supported his thesis by identifying the badly mutilated colossal head found in the temple by Butler (see below) as Zeus/Achaeus, whose cult and image, he believed, had joined that of Artemis during this short period. This head is now tentatively identified as an Antonine emperor, probably Marcus Aurelius (see Fig. 3.55 and Table 3.1). Hanfmann also maintained that the establishment of the plan as a pseudodipteros occurred during this “Achaeus” phase, 220–200 BC, an early date also supported by some in recent scholarship on Hermogenes.15 In sum, Hanfmann and Frazer, unlike Gruben, saw the cella division as a pre-Roman undertaking, but the three concurred that the adaptation of the pseudodipteral plan was a Hellenistic idea.

Hanfmann explained that the Roman reconstruction of the temple began soon after the earthquake of AD 17 and mainly consisted of the erection of the east peristyle and east pronaos porch columns over their Hellenistic foundations and bases; in this he differed from Butler, who had repeatedly asserted that the post–AD 17 Roman work on the temple was mainly a repair and was limited to the east end. However, he followed Butler’s theory that this Roman phase included strengthening the masonry block foundations of the peristyle columns using mortared rubble; he believed the actual independent ashlar foundations to be original Hellenistic work.

In Hanfmann’s scheme, during the middle of the second century AD, with the granting of neokorate honors to Sardis, the colossal images of Antoninus Pius and his wife Faustina simply joined Zeus and Artemis. The goddess and the deified empress shared the west cella, occupying the newly made image base. The extensive mortared-rubble construction, which is preserved between columns 73 and 74 (immediately west of the east crosswall and extending to the north wall), was interpreted as the foundation for this marble-clad base. The same material was used as foundation fill on the east side of the east crosswall, between this wall and the original image base (see Fig. 2.80). The temple was left unfinished, with only the major cella roofed and the fully standing columns of the east end balanced by some—if not all—of the columns of the west pronaos porch, which was approached by the makeshift arrangement of the northwest steps.

Gottfried Gruben

It is surprising that neither Butler nor Hanfmann, directors of the two American teams at Sardis, paid attention to the copious and clearly delineated techniques and construction details of the monumental building—details that provide potent and objective criteria for dating. Both were more interested in stylistic analyses of ornament or sculpture, or the greater events of local and regional history in relation to the city of Sardis, as the primary criteria for explicating the building history of the temple; the evidence of the stone itself remained unattended. We are indebted to Gottfried Gruben, the eminent German architectural historian of classical architecture, who, in a seminal publication in 1961, challenged Butler’s design and dating sequence.16 Gruben’s hypothesis regarding the building history of the Artemis temple is based on objective, though by no means conclusive, criteria: the observation of characteristic or unique masonry techniques and construction details, such as the shape and type of clamps, dowels, and lewis holes.

Gruben determined that there were two distinct construction techniques (“Technik I” and “Technik II”) used in the temple that provide reasonably secure criteria for distinguishing two major phases: Hellenistic and Roman. The early phase (Phase I) is represented by simple, bar-shaped clamps (also known as hook clamps); square dowel holes placed at joints or edges of blocks (kanten-dübel, or “edge dowels”); and a total absence of lewis holes. The Roman phase (Phase II) is characterized by butterfly clamps with or without depressed, hook ends, dowel holes with single or double channels (for pouring lead or using the channel for lead overflow), and the widely used standard-type lewis holes.17

Using primarily these differences, Gruben recognized that the thin east crosswall and the west wall were not parts of the original Phase I construction, but rather belonged to the Roman period. He was the first to point out that these walls do not bond into the north and south walls (Figs. 2.46, 2.49, 2.67), nor do their masonry courses match those of the long walls. The so-called middle crosswall, on the other hand, bonded into the north and south walls of the cella and displayed all of the typical features of the earlier, Hellenistic construction technique; this was identified as the original west wall of the cella.18 A monumental door in its middle, indicated by the telltale evidence of weaker, porous, sandstone foundations, would have been approached by stairs whose design, comparable to the door of the cella east wall, Gruben ascertained; he also correctly identified the foundations of its side or parapet walls (clearly shown on Butler’s plan but now gone). Gruben established the extent and the orientation of the west-facing original cella, thus eliminating the “treasury” theory.

Gruben proposed three major phases in the history of the temple (Fig. 3.2).19 The first, early Hellenistic period phase (300–280 BC) was represented only by the cella with its deep, west-facing, almost-square pronaos (17.91 × 17.69 m) and a short opisthodomos, one-third as deep as the pronaos (17.91 × 6.00 m). The pronaos had six columns in three pairs, the opisthodomos one pair, and the cella interior had twelve columns in six pairs. The temple was oriented to the west and separated by a spacious platform from the massive altar, the latter structure predating the temple. Drawing his influential parallels in part from contemporary dipteral temples such as the Temple of Apollo at Didyma and the second Artemision at Ephesus, Gruben proposed that the original temple was conceived also as a gigantic Ionic dipteros, but construction never advanced beyond the cella stage.

Gruben’s second phase coincided with Pergamene rule and influence at Sardis in the late Hellenistic period (190–150 BC) when the present pseudodipteral arrangement with 8 × 20 columns was adopted. The west-facing cella remained the same, as did the west porch, which he postulated was accessed by a flight of marble steps from symmetrical northwest and southwest sides. Therefore, the adoption of a pseudodipteral scheme at Sardis would be understood as a response to contemporary ideas on Ionic temple planning popularized by Hermogenes. However, Gruben noted the difference between orderly plans based on Hermogenes’s academic rules and the free and creative interpretation at Sardis, with its three-intercolumniation-wide east and west ends occupied by deep, amphiprostyle porches that precluded a continuous ambulatory of equal width as the side pteroma.

According to Gruben, these unusual porches were created by moving the pairs of pedestal columns forward from their original in antis positions between the pronaos and opisthodomos anta piers to their middle positions. Although none of the columns of the long north and south sides—and none except the previously described pair of pedestal columns of the west end—were started during this period, he believed that the six-column pronaos porch of the east side was fully finished.

More critical to the shaping of future proposals in the design of the temple was Gruben’s belief that the eight frontal columns of the east end and the last few from the east end of the north and the south sides (columns 9, 15, 14, 18, and 20) were already laid in their foundations during this later Hellenistic period. Gruben justified this view by observing and claiming that the construction techniques revealed by the tops of column foundations 9 and 15 on the north, and 14 and 20 on the south (the only positions on the east end not occupied by columns), identified them as Hellenistic (see Figs. 2.114, 2.115, 2.131, 2.133). These features are, primarily, the use of bar-type clamps instead of butterfly clamps; however, as a full study of these features indicates, bar clamps occur in Roman construction also on courses at or above ground level, and butterfly clamps occur below (as also shown by Thomas Howe, see below).20 Gruben supported his arguments for a Hellenistic date for the pronaos porch by holding that the fully finished bases, and the three capitals from the “small group” assigned to these positions (capitals C, D, and G), belonged to the Hellenistic period in terms of style, perhaps as early as the first phase of the temple, which he dated to ca. 300 BC.21

Gruben identified the third building phase as the division of the cella into equal parts during the Roman Imperial era. To him, the inscription recording the erection of column 4 carved on the fillet of its bottom drum (see pp. 190-193 below) and the colossal head of Faustina found inside the cella both suggested an early Antonine date for this phase of extensive building and renovation of the by-then long-neglected structure. He believed that the new “double temple” with its back-to-back cellas, like the Temple of Venus and Roma in Rome, would have incorporated the cult of the deified empress and that of Artemis.22 According to the German architectural historian, in order to create two spacious chambers of equal length, the original west wall of the cella would have had to be dismantled and rebuilt, including its monumental door and stairs, at a distance of 6.01 m from the west anta piers, thus shortening the original pronaos by two-thirds and creating a pair of identical porches at the east and west ends. The east wall would also have been partially dismantled and rebuilt with a new door and stairs leading up to the east cella. While the original image base remained in this space, a new base would have been created in the west cella, whose mortared-rubble foundation is preserved as a broad platform immediately west of the wall dividing the cellas, the east crosswall.

The reorganization of the west cella would have required some ingenuity, because the western half of the room, originally a part of the pronaos, ended up being ca. 1.60–1.70 m lower than the eastern half. An even floor was achieved by filling up the lower, eastern half of the pronaos. Telling evidence of this operation is provided by a clear, horizontal line of erasure across the upper surface of the Mnesimachos inscription, which was carved on the south, interior face of the northeast corner orthostat of the original pronaos (for a full discussion of this important inscription, see p. 163 below); the area below this line, marking the new, higher floor level, was buried; since it was not visible, the bottom part of the inscription was retained (see Figs. 2.54, 2.100).

The roof of the new west cella presented a problem because its interior supports represented two different spans or systems: the four interior columns of the original cella (columns 73–76) are on a different alignment and are spaced far wider apart than the columns on the western side of the new room (columns 77 and 78). Thus, they cannot be reconstructed with a proper architrave following a continuous straight line (see pp. 203-205 below). Gruben offered an ingenious and simple solution in his suggestion that the ineffective column pair 77–78 had been demolished and replaced by a pair of piers some 5.60–5.80 m to their east. Preserved in their foundation courses directly east of the dismantled west wall (middle crosswall), these coarse “piers,” follow more or less the alignment of the cella columns (for a reconsideration of this proposal, see pp. 67-68). As Gruben explained, they carried the timber trusses of the new roof, and there was thus no need to alter the interior columns or the roof of the east cella.23

The mid-second-century Roman building of the perip-teros would have included all eight columns of the east front (over Hellenistic foundations, Gruben believed, as did Hanfmann and Frazer), almost all of the column foundations of the north and south colonnades, and possibly the remaining five (or all six) outer columns of the west pronaos porch, making it the mirror image of the eastern one. None of the columns of the west front, except southwest corner column 64, had been started even in their foundations, although it appears that they were planned, because there was just enough distance for a row of columns west of the great altar.

In studying the metrology of the Hellenistic temple, Gruben adopted an Ionic foot of 29.52 cm (one millimeter longer than the Ionic foot of Didyma) and rounded his figures when necessary, thus making the millimeter-accuracy of the Ionic foot moot. Gruben proposed a twenty-foot interaxial module, which gave an overall interaxial length of 300 Ionic feet and a width of 150 Ionic feet (actually 148.75 feet) for an 8 × 16 temple. He noted the discrepancy between the alignments of the present peristyle columns and those inside the cella, confirming the chronological difference between them—the cella came first, then the peristyle. Gruben’s ideal, dipteral scheme based on an imaginary interaxial distance of 5.90 m (20 feet) is a theoretical construct; the actual interaxial width of the peristyle columns is ca. 5.83–5.85 m. What is more cogent and convincing in his argument is the possibility that a dipteral arrangement conforming to contemporary principles of Ionic temple design could have been achieved using simple modular ratios based on plinth sizes, interaxial distances, and column heights, i.e., a system based on geometry.24

Wolfram Hoepfner

In a 1990 study devoted mainly to Hermogenes and his architecture, W. Hoepfner focused on the Temple of Artemis at Sardis as an example of the high Hellenistic pseudodipteros, predating Hermogenes by roughly half a century and providing him with a system of temple design based on whole-number ratios of lower diameters and intercolumnar distances. According to Hoepfner, this system, viewed as part of a tradition represented by the complex (“multiple”) contractions of the frontal intercolumniations at Sardis (and the late Classical Artemision at Ephesus), was passed on to Vitruvius by way of Hermogenes. Thus, an early date for the Sardis pseudodipteros was important for Hoepfner’s thesis.

Eliminating Gruben’s second Hellenistic building phase altogether, Hoepfner maintained that the temple was designed from the onset, ca. 300 BC or slightly later, as a giant pseudodipteros that was finished only during the Roman Imperial era. Instead of its present, unusual plan, Hoepfner proposed that the original temple had traditional amphiprostyle, tetrastyle porches with pairs of pedestal columns in antis and four prostyle, directly in front of the antae. Thus, in this scheme the temple displayed a more “correct” and orthodox pseudodipteral plan with a continuous ambulatory two intercolumniations wide.25

During the Roman Imperial era, the two pedestal columns in antis were moved forward to their present locations by leapfrogging them over the two middle columns (numbers 10 and 13 in Hoepfner’s plan) of the proposed tetrastyle porch, as these two were dismantled and brought out diagonally to the corners of the newly created pronaos porch. Hoepfner’s interesting, eye-catching, but orthodox proposal was put to test and to rest in 1996 when we opened a deep trench inside the east porch where one of the columns of his hypothetical tetrastyle porch was expected to stand (number 13, the third column from the north in Hoepfner’s plan). The trench reached a depth of 2.50 m below the surface and exposed only the purplish clay of the bedrock (*98.25–97.76); above this was the earlier occupational layer sprinkled with Lydian sherds.26 It is a pity that some recent scholarship accepts Hoepfner’s thesis—though perfectly reasonable as a hypothesis at a time when archaeological evidence was lacking—as fact without any questioning.27

Thomas Howe

The most recent work on the building history and design of the Temple of Artemis was undertaken by Thomas Howe, who was the chief architect of the Sardis Expedition from 1980 to 1982. His conclusions, published in 1999, refine and simplify the framework of the chronology set up by Hanfmann and Gruben, and are largely borne out by our long-term fieldwork.28

Contrary to Hanfmann and Gruben, Howe proposed two rather than three major building phases: Hellenistic and Imperial Roman. According to Howe, the temple was a Seleucid project begun a generation or two after Alexander. During the first phase (280–200 BC) the west-facing cella and its interior columns were finished, but the exterior peripteros of columns, “whether planned as a dipteros or pseudodipteros, was not begun.”29 If the original building was intended to be a dipteros, the proportions of the exterior colonnade could have been a simple, modular grid based on a column base or an anta plinth, rather than one following the complex numerical ratio proportions typical of third-century BC temples.

Skipping the late Hellenistic (or “Pergamene”) period of earlier hypotheses, Howe saw the cella division and the building of the exterior peristyle as broadly contemporary activities belonging to the Roman imperial period, or the “second phase” of the temple. Following and refining Gruben’s powerful analysis of construction techniques, Howe was able to surmise that the full peristyle, including the foundations of the east colonnade, used a clamping and doweling system different from the Hellenistic construction of the temple. He argued that the evidence—including the colossal heads of Faustina and Antoninus Pius found in the cella and the second neokorate awarded to Sardis, probably under the same emperor—indicated that the undertaking to finish and redesign the temple as a joint temple to Artemis, Zeus, and the imperial cult was an Antonine project. He also evaluated the uniquely spacious pronaos porch as an arrangement closer to that of a Roman pseudodipteros, such as the Temple of Zeus at Aezane, or the early Imperial pseudodipteros known as the “Wadi B temple” at Sardis (see for Aezane, Fig. 3.74; pp. 218-219 below; Fig. 3.72), rather than to the arrangement of a Hellenistic temple with the characteristic columns in antis cella design.30

Howe presented a convincing and cogent thesis that the Antonine re-creation of the Temple of Artemis at Sardis marks the end of a conservative, late Hellenistic tradition of temple design whose origins reached back to Hermogenes.31 However, his association of the temple with the Zeus cult, an old and intriguing idea, finds no support.

-

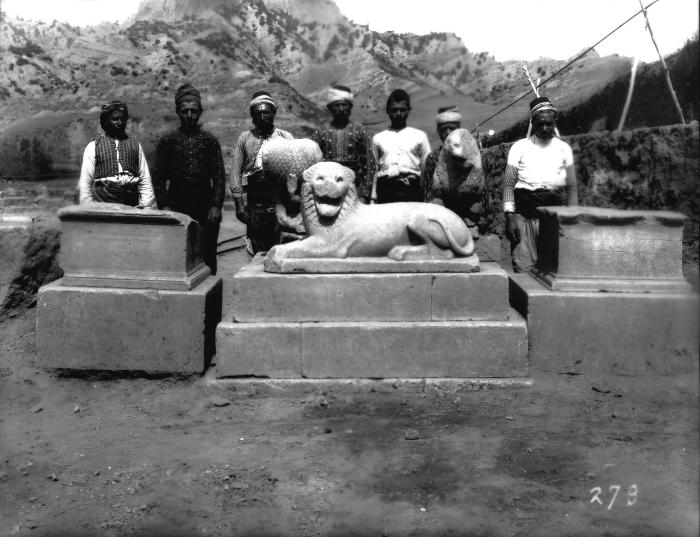

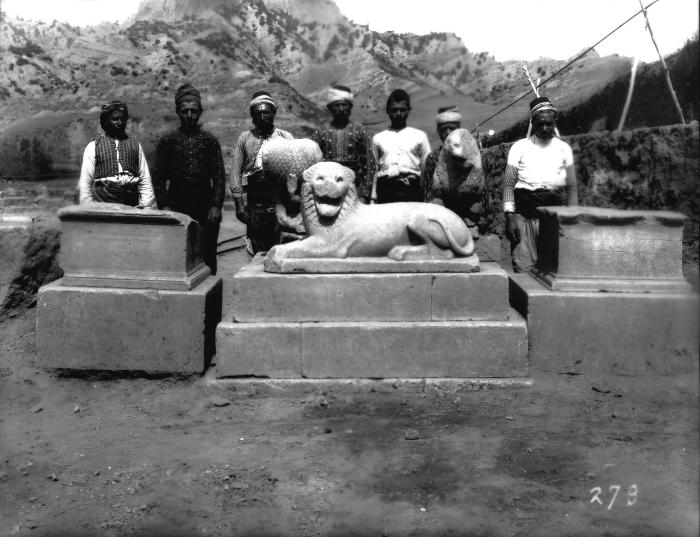

Fig. 3.32

West crosswall trench (2010), northern end foundations, west face (looking southeast). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 2.64

Rendering by the author of west crosswall connection to south wall. (Fikret Yegül, ©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 2.65

West wall, interior face, covering column foundations 80 and 79 (with column base 78 in foreground) (looking northwest). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. Plan 6

Temple of Artemis, Sardis, state plan, drawn 1:100 (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 3.1

Hypothetical restoration by Butler of the west end of the temple, incorporating the “Lydian Building” (LA 1 and LA 2). (Sardis II.1, ill. 97.)

-

Fig. Table 3.1

Colossal Sculpted Heads Found in Association with the Temple of Artemis at Sardis (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 3.55

Colossal head fragment (Sardis inv. S61.27.14), identified as Marcus Aurelius (or as “Zeus” by Hanfmann), Sardis excavation compound. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 2.80

East crosswall dividing Roman east and west cellas, with sandstone basis in east cella and mortared rubble platform in west cella. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 2.46

East crosswall top, connection to north wall (looking north). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 2.49

East crosswall top, connection to south wall (looking south). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 2.67

West wall, connection to north wall (looking southeast). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 3.2

Gruben’s building phases of the Artemis temple. Top: Early Hellenistic (300–280 BC); center: Hellenistic (190–150 BC); bottom: Roman Imperial. (After Gruben, AthMitt 76, 1961, pl V.)

-

Fig. 2.114

Column foundation 9. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 2.115

Column foundation and plinth 15, without capital F. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 2.131

Column foundation 14. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 2.133

Column foundation 20, with plinth and drum. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 2.54

Middle crosswall, northern end, connection to north wall (looking north). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 2.100

Middle crosswall, northern end, with Roman northern rough pier. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 3.74

The Temple of Zeus and its terrace, Aezane. (Krencker 1936, in Schede and Naumann 1979)

-

Fig. 3.72

Wadi B temple and terrace. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

Historical, Epigraphic, and Numismatic Considerations for Design and Chronology

The following section presents considerations and proposals for a revised building history for the Temple of Artemis at Sardis, one partly based on the ideas of previous scholars but mainly on the reevaluation of historical, epigraphic, ceramic, and (scant) numismatic evidence. Primary to this thesis, however, is the close study of the technical details of construction and architectural documentation of the temple (undertaken between 1987 and 1998) as well as limited archaeological investigations (sporadically since 1960, but mainly in 1972, 1996, 2002, and 2010–12). These new studies allowed the formulation of new proposals for the sequence of design and construction and provided clues to the temple’s chronology. However, in a number of instances they led to diverse interpretations of the evidence, sometimes with differences in end results.

In this study I have tried to include the sanctuary’s religious and cultic associations, especially the incorporation of the Roman imperial cult; comprehensive studies of religion and cult at Sardis obviously belong to other venues. In a short section devoted to the archaeological yield from a small trench between the northeast anta and column 16, I examine varying views based on ceramic and construction evidence. A review of some six or more colossal, iconic images of the Antonine era found inside or close to the temple indicates that they were an integral part of the temple’s design and usage in the Roman period. Finally, in a separate section devoted to architectural analysis and comparison I consider the temple’s unique design in the larger context of Hellenistic and Roman pseudodipteral temples in Asia Minor, as well as its potential connection to Western and Italian temple design.

Historical Considerations

The inspiration for the Temple of Artemis belongs to the Hellenistic world of inquiry, one of ideological and materialistic expansion that was ushered in by Alexander the Great.32 The conqueror did come to Sardis when the city surrendered peacefully in 334 BC, but we have no records that connect this visit directly to the temple history. According to the Greek historian Arrian, Alexander gave orders to build a temple to Olympian Zeus on the heights of the Acropolis, but there is no mention of endowing a temple to the Sardian Artemis.33

Stratigraphic soundings in the east cella of the temple in 1960 provided sufficient evidence for Hanfmann to assert that there had been no earlier temple under the present structure, and that conclusion has not been changed by our various investigations in the temple through 2010–12. However, evidence for continual occupation of the site during the late Lydian and Persian periods (mid-sixth to fourth century BC)—and for the presence of a sanctuary or a precinct sacred to the goddess—that predates the Hellenistic temple includes ceramics, the Archaic altar (LA 1), and the sandstone image base (“basis”) inside the cella of the temple (see pp. 163-164).34

There is general agreement that the colossal temple building was started under the Seleucids, soon after the Battle of Koroupedion in 281 BC, in which Seleucus I Nicator (r. 301–281 BC), the founder of the dynasty, defeated Lysimachus (a Macedonian general of Alexander) near Sardis and gained control of most of Asia Minor.35 This was the historical and political turning point that would have rendered the conditions convenient, even necessary, for such a prominent civic project. It is also an opportunity to link a great building to a “Great Man” and a great event—a satisfying theory, though not always true or expedient.36 We have no hard evidence that this was so, but a late fourth-century BC date is technically possible.

The assumption that links the temple to the new Seleucid rule is, however, based on two cogent and logical considerations. First, only a strong, stable dynasty could support such a large and expensive project. Second, after the conquest, Sardis remained an important city and assumed a special position among the cities and sanctuaries of western Asia Minor as a royal center of the Seleucid reign and an official residence (or one of the official residences) for its monarchs. As the site of the western terminus of the widely traveled Royal Road, the city’s historical and geographic position was too important to be entrusted to any but the leading power-holder of the new dynasty. It was the first place where Antiochus I and Queen Stratonike stopped to burnish the Seleucid royal presence after the untimely death of Seleucus I in 281 BC, and that is where Stratonike, an exceptional royal woman with a penchant to revive or recreate cult centers with political significance, both lived most of her life and peacefully died, as discussed further below.37

An equally important indicator of the city’s importance as a capital, perhaps, was the location of the royal archives.38 After conquering the city and establishing peace, Seleucus I and his successors had powerful motives for founding a proper temple in the old Sanctuary of Artemis at Sardis to rival those of Ephesus and Didyma.39 The former was the home of the older Artemis cult, which was related to the Sardian cult; the latter was represented by a major temple—a well-documented bequest of Seleucus I himself—comparable to the Sardis temple in many aspects of its construction and detail.40 Appealing to local deities and cults in post-Alexandrian kingdoms and committing large sums of money for major building (that is to say, land you build on is land you own) was not simply a politically motivated measure but rather an active step in exploiting the opportunity to legitimize the dynastic claims of their rulers. In working to revive older, pre-Achaemenid local and regional cults, and rebuilding or building new major temples in major sanctuaries, it would be sensible to assume, the Seleucid rulers were calling attention to their difference from the Achaemenid rulers, who were known for establishing great temples in the East but were strangely unmotivated to do so in their western colonial centers. As Rostovtzeff observed long ago, “there was probably no Greek city in the Seleucid Empire without a cult of the reigning sovereign, his family, and his ancestors.”41

We do not have independent evidence for a specific Seleucid ruler cult at Sardis, much less in the Hellenistic temple, but there was general interest in and a political advantage to establishing dynastic cults in close association with local ones. Such a politically motivated association might have paved the way for the inclusion of the Roman imperial cult in the Temple of Artemis in the second century. The same political benefits for cultic transparency and continuity was not lost to the new Roman rulers as they assiduously preserved and encouraged these Seleucid ruler cults and their priesthoods in the Seleucid centers of Asia Minor, even long after the dynasty had become extinct.42

Queen Stratonike and Sardis

Seleucus I was killed in 281 BC, only seven months after his victory over Lysimachus. If the Sardian temple was a Seleucid project, then real work on the building could not have started before the reign of his son and successor Antiochus I, and his wife, Queen Stratonike—that is, by the end of 281 BC or soon after. While firm epigraphical evidence for Seleucus’s involvement in the Temple of Artemis at Sardis is lacking, he is credited for building the Temples of Zeus at Olba and Cilicia, and one much closer to Sardis, donating lavish gifts to the near-contemporary Temple of Apollo at Didyma, which must already have been under construction early in his reign. One would expect that his generosity toward Sardis, the famed capital of the Lydian kings and now his city, where he had defeated a strong foe, would not have been anything less.43 Even if he had no time to build or start such a temple, he would have bequeathed the desire and intention to do so to his son and erstwhile wife.

Stratonike, daughter of Demetrius Poliorcetes (“Besieger of Cities”) and granddaughter of Antigonus I Monophthalmos (“One-Eyed”), was Seleucus’s wife before he divorced her in 294/93 BC so that his lovestruck son could marry her.44 It is tempting to imagine this beguiling queen—whose life story has inspired generations of artists, writers, and musicians—visiting or even residing with her royal husband in their newly acquired capital, Croesus’s golden city, and honoring the Great Goddess with a temple, as she had done earlier for the local goddess Atargatis at Bambyce (Hierapolis) in Syria.45 She was also known to have made many offerings to Leto, Apollo, and particularly Artemis at Delos.46

Although there is no obvious evidence that Stratonike played a leading political role in both of her Seleucid husbands’ reigns, modern scholarship views her as a wealthy patron of religion, active and involved in honoring local cults as much as enjoying being the subject of cult worship herself (as “Aphrodite Stratonicis” in Smyrna: Orientis Graeci inscriptiones selectae XI.4, 228 and 229), not a passive pawn in convenient marriage arrangements. Stratonike’s position as a “lifelong ambassador,” or bridge, between cultures and dynasties would have guaranteed her close involvement in the religious affairs of the Seleucid-controlled cities of Asia Minor, particularly Sardis, which she had made her own.47

A Babylonian account from the reign of Antiochus I for the years 276–274 BC confirms that Sardis, once a military and administrative center of the Persian stratege and a well-known stronghold, was the official residence of the Seleucid king and his queen, Stratonike, at least during this period. According to this source, on his way to confront the Egyptian army in Syria Antiochus “left behind his [court], his wife, and the crown prince in Sapardu [Sardis] in order to strengthen the garrison [in Ebir-Nari, Egypt].”48 Another Babylonian record, a plaque with an astrological calendar, informs us that Stratonike died at Sardis between September 24 and October 24 of 254 BC.49 The mother queen, who had probably married her younger daughter Stratonike II to Demetrios II, the bride’s Macedonian cousin, during the same year (or a year earlier), must have been sixty-two or sixty-three years old when she died.

Curiously, barely two generations earlier, Sardis had been home to another powerful Hellenistic queen, Cleopatra of Macedon, the daughter of King Philip II and Queen Olympias, and thus the sister of Alexander the Great. After her beloved brother’s death in 323 BC, many of his generals sought her hand in marriage (which would have increased their chances in succession and become king), but in the end, none succeeded. The rivalries and intrigues among the contenders and retainers caused Cleopatra’s semi-exile in Sardis to prevent her from upsetting the balance of power.50 Cleopatra, brave and resourceful, but isolated from her Macedonian power base, stayed at Sardis for twelve years, perhaps because she was in some ways happy there, or else because she had no options.51 After an unsuccessful attempt to escape from the city, probably to marry Ptolemy of Egypt, she was brought back and assassinated in 308 BC, at age forty-six or forty-seven, on the order of Antigonus I Monophthalmos. Anticipating the political backlash that would result from the murder of this fiery and beautiful Macedonian princess (and queen of Epirus), Antigonus put the assassins to death and gave Cleopatra a fine funeral in Sardis.52

An early admirer of the power, personality, and intelligence of these queens, Grace H. Macurdy aptly commented that “like many unscrupulous women of this extraordinary northern breed . . . Cleopatra was murdered by men who feared her power and prestige.”53 Stratonike, as she strolled the gardens of her royal residence at Sardis, would have known all this. As a woman of that “extraordinary northern breed” herself, she must have pondered the tragic fate of her less-fortunate kinswoman, probably with wistful thoughts about her own future—it was a hard world, and for many women, it is still a hard world.

A particularly intriguing indicator of Stratonike’s connection to the city and to Sardian Artemis is a dedication found in the Temple of Artemis, a marble ball ca. 36 cm in diameter, bearing the inscription “[Gift] of Stratonike, daughter of Demetrios the son of Antigonus.” The letter forms indicate that this is a mid-second-century BC Hellenistic copy of the original gift, which must have been made during Stratonike’s lifetime, that is, early in the third century BC and presumably soon after the city came under Seleucid power in 281 BC.54 This may be true, but it does not alter the historical usefulness of the evidence; copies of inscriptions of cultic, archival, and political significance were common. However, there are also some doubts about the authenticity of the inscription, as Stratonike’s royal title and her husband Antiochus’s names are missing.55 However, in inscriptions on the queen’s other known offerings the name of her husband and her dynastic titles are often omitted in favor of her father’s name. This is especially true of her lavish gifts at Delos; she never calls herself “queen” or “wife of Antiochus” but simply “daughter of King Demetrius.” One explanation could be that she made this offering before she married her husband in 294 BC; or that she was following the third-century practice of omitting the husband’s name in dedications made by Hellenistic women.56 The more convincing answer, I believe, is to be sought not just in her well-documented devotion to her father and her clan, but also in her sense of independence.57

One might point out that even an authentic dedication by Sardis’s queen does not in and of itself prove that the temple existed; she may have made the dedication to the sanctuary of Artemis before the temple was built; there are a number of such dedications that predate the temple but were later set up in the sanctuary. However, there is no clear information that leads to such a conclusion either. The argument here is based on the strength of Stratonike’s historical personality and connection to Sardis, as she made the Lydian capital her own; the discovery of the dedication inscription (or its later copy) is an additional indicator of this special kind of involvement. It also takes into consideration her deep sense of religiosity, particularly her devotion to Artemis, which would have been an effective supporting factor for why the temple was initiated during her reign and residence as basilissa in Sardis.58 Despite justifiable caution, I maintain that it was Queen Stratonike who made the dedication to Artemis at Sardis, and this makes it possibly the earliest physical document we have that is associated with our temple.59

Mnesimachos Inscription

An equally important inscription in Greek carved on the interior northeast corner of the west pronaos wall of the Temple of Artemis records in detail the mortgage obligations of a certain Mnesimachos in return for a loan he received from the temple funds (see Fig. 2.54). The display of official deeds and records on important public buildings represents a well-known ancient tradition. Mnesimachos’s extensive estate, which had been granted to him by a king (including land, villages, dwellings, slaves, and other revenue-bearing assets), is described as a kind of collateral (in the modern sense) against this loan.60

Considerable controversy exists, however, about the nature and date of this important inscription, which naturally is central to the question of the dating of the temple itself.61 If the Antigonus mentioned in this inscription is Antigonus I Monophthalmos (r. 306–301 BC), the founder of the Antigonid dynasty of Macedon, the date of the original mortgage document, perhaps carved on a stele, would be somewhere between 300 and 250 BC, since Mnesimachos could not be expected to have survived the king by more than about fifty years.

Mainly on epigraphic grounds, many scholars consider the text carved on the temple wall to be a later copy of an earlier document broadly datable to 250–200 BC.62 Thus, like the Stratonike inscription, the evidence provided by the Mnesimachos inscription favors a building that was largely complete and in use by the second half of the third century BC.63

Another piece of circumstantial but critical evidence for the completion and use of the temple by the mid-third century BC at the latest comes from an inscription found in Didyma. This stele records a deed of sale of land by Antiochus II in 254/53 BC to his divorced queen, Laodice. The original document was placed in the “royal archives” at Sardis, but copies were displayed in four other major sanctuaries (Ephesus, Ilion, Samothrace, and Didyma). As pointed out by Gruben, it is unlikely that the Sanctuary of Artemis at Sardis would have been selected for this honor if it did not have a functioning temple at that time.64 Dedications, votive steles, and inscriptions carved on statue bases found among the ruins of the building provide additional epigraphic testimony in favor of the continued use of the temple through the late Hellenistic and early Roman periods.65

Coins from the Image Base (“Basis”)

A group of 126 Hellenistic coins (54 silver coins along the east side of the image base and 72 bronze ones along the north) and one silver croeseid (in the center) were found inside the purple sandstone foundations of the base (“basis”) located in the center of the original cella (now the east cella), which was believed to have carried the image of Artemis when the temple was constructed around it. These foundations, preserved as two courses of ashlar and occupying the entire area between columns 69/71 (north) and 70/72 (south), would have been covered in marble to create a large (ca. 3.60 × 3.60 m) but low square platform, rising ca. 0.50 m from the cella floor (Figs. 2.80, 3.3, 3.4, 3.5).66

Butler, noting the tightly fitted blocks finished with a fine flat chisel and joined by many large “pi-shaped clamps” (bar/hook clamps)—comparable to Lydian masonry at Sardis—as well as the single croeseid coin, considered the base to predate the temple. Few of these clamp cuttings are visible now; they must have been destroyed or eroded in 1914 when Butler dismantled the soft-stone blocks and opened a three-meter test pit in the center of the cella to look for earlier structures (none were found), leaving the blocks lying in heaps. In 1960 the Harvard-Cornell Expedition attempted “no more than putting the chaos of stones into some semblance of order and filling the hole in the east cella.”67 Some 102 blocks were measured, numbered, and put in place in two courses according to a tentative reconstruction. We have no reliable drawings or photographs of the base before it was dismantled. Therefore, the way the stones of the platform have been drawn and placed on the site does not represent with certainty how they originally were.

Hanfmann and other scholars settled on a date around 220–190 BC for the construction of the base from the evidence of the reused blocks.68 This conclusion was questioned by P. Stinson, who noted that the unusually broad placement of the cella’s column foundation blocks around the central platform must signal the builders’ attempt to accommodate this preexisting structure, although the actual spacing of the columns above them would not have been affected. Compelled by this observation, N. Cahill opted for Butler’s pre-temple date for the base. He pointed out that the Hellenistic bronze and silver coins used to date it were found “in the vertical joints between the stones of the upper course . . . as if at the foot of the pedestal of the statue,” while the silver croeseid was between horizontal courses; it can thus be linked to the actual time of construction and is compatible with the ceramic and masonry stylistic evidence.69

-

Fig. 2.54

Middle crosswall, northern end, connection to north wall (looking north). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 2.80

East crosswall dividing Roman east and west cellas, with sandstone basis in east cella and mortared rubble platform in west cella. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 3.3

East cella purple sandstone basis after 1960 excavations. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 3.4

Sections through the east cella purple sandstone basis. A. East–west with column foundations 71 and 69 and south face of north wall (looking north). B. North–south with column foundations 72 and 71 and east face foundations of the east crosswall (looking west). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 3.5

East cella, column foundations 69–71, and late foundation blocks with basis beyond them (looking southwest). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

Materials and Methods of Construction: Technical and Stylistic Considerations

Historical and epigraphic evidence, often inconclusive and circumstantial, provides a broad contextual backdrop against which our primary interest and methodology—employing the construction details of the building as a dating tool—may be measured. Careful observation of the temple construction, including the details of its marble ashlar walls and the foundations of its walls and columns, has provided us with a set of more objective criteria for distinguishing what we see as two main construction phases.70 These technical features evidently represent the work of two major periods and were used consistently in the construction of the temple. Though these features have been described previously, they will be summarized in this section as well. Some, but not all, of the observations in the following discussion are similar to those that Gruben published in 1961 and are supported for the most part by Howe. In certain details I offer new possibilities.71

Main Walls and Foundations

Significant details that clarify the construction processes of the Artemis temple appear consistently in the long north and south walls, the east wall, the original west wall (middle crosswall), and in the foundations of the twelve interior columns of the original cella. These include the use of bar clamps (with hooked ends), square dowels without channels (used as edge dowels below floor level and in combination with leverage holes at or above the euthynteria level), and a total absence of lewis holes (see Figs. 2.9, 2.15, 2.22, 2.60, 2.62). We may identify these characteristics with the temple’s original, Hellenistic construction, or first phase.

The Roman (second) phase construction is represented by the east crosswall, the west wall, and all of the foundations of the exterior columns of the peristyle, as well as the column foundations of the east and west porches (where preserved or visible). This construction is broadly identifiable by the use of butterfly clamps (without end hooks; “wing clamps” in some publications) for the courses below the floor, or the euthynteria level, but regular bar clamps (though of a larger size than those typical for Hellenistic construction) for courses at or above the euthynteria level (as observable in the case of the foundations of columns 9 and 14: see Figs. 2.114, 2.131). Square dowel holes with single or double pouring channels are common. Standard-type lewis holes (large in size and with double slanting sides) are universally used; very large blocks, such as some of the column drums and architraves, commonly use two or more lewises. Rarely are L-shaped, T-shaped, or cross-shaped lewises employed, although these shapes may exist due to the later reworking of standard lewises.

Below is a detailed description of these Hellenistic and Roman features.72

Hellenistic Phase Features

Walls identified with the first phase of construction, as readily seen in the south and north walls and the original west wall (middle crosswall), are built of larger, more uniformly shaped blocks that are well joined and fitted and display a smooth finish. Surface cuttings or construction cuttings (clamp, dowel, and leverage holes) are employed sparingly; no lewises appear except in the Roman reuse of such blocks, such as the fluted drums. The courses below the euthynteria level (-1), as seen on the western end of the south wall, are so closely and finely fitted that they required no clamps or any other cuttings except for small, square dowels. Courses at or one course above the euthynteria level (0 and +1) are joined by a row of bar clamps (ca. 12–16 cm) applied along the outer edge of the wall; courses above this level (+2 and higher) have two rows of bar clamps along both the outer and inner edges of the wall; clamps are never used to join blocks laterally across the width of the wall.

The unclamped joints of foundation blocks of the courses below the euthynteria approximate the tightly fitted, quasi-polygonal technique and must have been conceived as a structural device to retard or offset differential settlements (as visible in the connection of the middle crosswall and the south wall; see Fig. 2.60).73

The technical features (mainly clamps and dowels) of the north and south walls of the cella display a roughly consistent system of distribution patterns specific to courses: edge-type dowels are used in combination with a leverage hole, often located in a row ca. 0.20–0.25 m from the edge of the wall, and without the use of pour channels. In the case of the edge dowels, lead was poured in from the edge after the dowel was put in place, and then the next block was lowered and shifted into position with the help of a crowbar. All clamps are of the bar type, with ends anchored into the stone (see Figs. 2.20, 2.21, 2.22, 2.23, 2.24); they are small or medium in size (12–16 cm) and run in rows close to the outer or inner face of the wall, or both; there is no lateral or cross joining of the blocks (see Figs. 2.15, 2.16, 2.17). These construction features and details also characterize the individual column foundations inside the original cella and the west pronaos (see pp. 60-67).

Roman Phase Features

The blocks of the Roman (second) phase, especially the column foundations of the north and south peristyles and the west pronaos porch columns (column foundations 48, 53, 54, 55, and 49), are massive, coarsely shaped, and characterized by an excessive use of clamps. Clamps above foundation level are uniformly of the bar type, while the foundation courses below often display larger butterfly clamps without end depressions.

Blocks for the east crosswall and the west wall, both Roman additions, are not as tightly or carefully fitted as the earlier Hellenistic work; smaller stones fill the wall middle (for the east crosswall, see Figs. 2.46, 2.47, 2.48, 2.49; and for the west wall, Figs. 2.67, 2.68; see also Figs. 2.9, 2.10, 4.11). While in the Hellenistic work only the outer row of blocks of a course are joined by a carefully aligned row of clamps, in the later construction almost every block is joined to its neighbor by one clamp, and often two or three. Dowel holes, when used, are accompanied by one or two pouring channels at the corners. Three of the unfluted column drums display pairs of small, square dowels of the “dry dowel” type, typically with a bronze casing to receive a dowel that would have matched exactly and did not require the use of lead; it is likely that this method was more common than the preserved evidence suggests, considering that the metal would have been an easy target for robbers.

The use of standard, rectangular lewis holes is ubiquitous; even relatively small blocks bear at least one lewis hole, and larger ones have two or more. The lewis holes are conspicuously large, deep, and coarsely cut (averaging 10.0–12.0 × 4.5–7.0 × 7.0–10.0 cm for the crosswall blocks and 12.0–17.0 × 6.0–9.0 × 10.0–18.0 cm for the north and south peristyle column foundations).

The use of masses of mortared rubble (a local variant of opus caementicium), which thoroughly encases the marble block foundations of the exterior columns, is a patently Roman construction on the site (see pp. 68-73). Although there are instances of mortared-rubble construction dating to the first century AD in Asia Minor and at Sardis, such as the Wadi B temple (ca. mid-first century AD; see pp. 217-220), the system becomes widespread during the late first and second centuries, as exemplified by large projects at Sardis such as the Bath-Gymnasium Complex and the great end walls of the theater (the date of the latter may be late first or more likely second century AD; Fig. 3.6). Like these instances, the mortared rubble of the Artemis temple appears coarsely and unevenly laid, using a surplus of rubble stones and less lime mortar.

In some cases, the consistent use of these techniques, both Hellenistic and Roman, is compromised because a wall or a part of a wall has been rebuilt using blocks from an earlier construction. This is especially true for the west wall and the preserved northern end of the middle crosswall (see Figs. 2.54, 2.58, 2.59, 2.62). Only six meters from the end of the west anta piers, the former is of “mixed construction”: some blocks show predominantly Roman features, but there are a few that bear smaller bar clamps with hook ends, even below the foundation level; this represents reuse from the earlier phase. The west wall bonds to neither the south nor the north long wall, nor does it match their masonry coursing (observable only at its northern end). It is laid directly over the foundations of the pair of original column foundations of the pronaos (column foundations 79 and 80, not on Butler’s plans). We can imagine that the late west wall was built mainly from the stones of the demolished original west wall (now called the middle crosswall) of the cella, including its central door and staircase.

The western end of the north wall also shows mixed construction, with bar clamps used on courses above ground level and butterfly clamps below ground level. The foundations of the northwest anta pier (Hellenistic) and column 48 in front of it (Roman) are connected along a joint with three large butterfly clamps, while the blocks of the anta pier above grade have bar clamps. In the same area, there are no lewises on the side of the anta pier, but many are visible below and above grade on the column side (Fig. 2.107). Differences in construction techniques are particularly dramatic at the western end of the south wall and the southwest anta pier, where the abrupt change from Hellenistic to Roman construction (and the seam between the two) can be seen very clearly on the preserved surface of the wall, 7.50–7.60 m from the reconstructed face of the missing southwest anta pier, as well as along the south face of its foundations (see Figs. 2.9, 2.10).

The East Door

Structural and Stylistic Considerations for Dating

Butler believed that the temple was meant to face east and that the east door was its original door. Hanfmann and Frazer held that the east door was a late feature, belonging to a “late Hellenistic” phase (see Figs. 2.28, 2.29).74 However, the evidence provided by the masonry construction below the threshold and around the door opening, along with the style of ornament of the well-preserved door jambs, indicates that the east door was cut during the Roman period when the cella was divided into two separate chambers (for a description of the construction below the threshold of the east door, see pp. 46-49). In Greek and Roman architecture, construction directly under door openings is typically and intentionally left “weaker” for reasons of economy because that area supports less weight. The threshold of the Artemis temple’s east door is supported by continuous marble-block construction no different from the foundations of the main walls of the cella, a clear indication that the east wall was originally solid, and that the east door was not an original feature of the Hellenistic building.75

The two courses visible below the threshold were left largely rough, leading one to believe that they were intentionally unfinished because the original design included a door and stairs that would have masked this part of the lower wall (see Figs. 2.28, 2.36, 2.37, 2.38). Close examination, however, reveals that these courses below the threshold were partially finished; a pair of smooth, finely dressed blocks of the second course below the threshold continues some distance under the door on both sides (see Fig. 2.43). The blocks of the middle portion of this course (for a length of 5.14 m) display a coarse, quarry-faced surface with a smoothly drawn, 6–7 cm wide “drafted edge” along their top edge. The course above this is left entirely rough with no drafted edges at the joint. The rough areas of the course below the threshold thus actually represent work in progress. Their smoothed horizontal and vertical bands are not “drafted edges” of finished masonry, but guides for trimming the surface of the rest of the block—a standard detail indicating that work progressed in stages, moving from the wings to the center of the east wall. If the original builders had planned for a door here, there would have been no finished or half-finished blocks under the threshold. Why trim masonry that would have been invisible behind the massive stairs of the door?76 It appears then that at the time the door was cut open, finishing work and detailing on the opisthodomos walls were only partially completed, moving from the flanks to the center—a normal procedure.

Further evidence for the later date of the door can be evinced by observing the pattern of the masonry courses on both sides of the door opening. The third and fourth courses (up from the porch floor) adjacent to the south jamb of the door are 0.74 m and 0.44 m long, respectively; the fourth course on the north side is 0.60 m long (see Figs. 2.30, 2.37). These are uncommonly short blocks in relation to the temple’s scale and the normal length of its ashlar blocks. In fact, they are the shortest three of the more than 356 blocks that are preserved in situ and visible on the cella walls (typical block lengths run 1.20–2.20 m). Furthermore, they appear anomalous to the regular long–short alternating rhythm typical of Hellenistic ashlar masonry in this temple and elsewhere. This anomaly is a strong indicator that the center of the east wall was taken down to its lowest course, and that some of its blocks were either cut shorter or completely replaced in order to accommodate a large door centered on the cella axis.

While I hope that these structural considerations are sufficient to show that the east door is a late addition, they do not necessarily prove that it is Roman; Hanfmann and Frazer believed that it was part of a late Hellenistic renovation.77 However, internal construction evidence that points to a Roman date is provided by the very large lewis holes and channeled dowels carved on the upper surfaces of the door jamb blocks, which are typical construction features of the Roman period (see Figs. 2.35, 2.36). Furthermore, stylistic considerations of the jamb and cornice ornament of the door allow us to narrow down the dating to the Hadrianic period.

Ornament

With the exception of some capitals, decorated bases, and several pieces of the unornamented inside (pteroma-facing) architraves (one fully preserved), extant Roman ornament on the temple is restricted to the jambs and lintel of the east door and the enormous consoles flanking the lintel (see Figs. 3.7, 3.27).

The presence and prestige of the Hellenistic temple, especially its superbly modeled and carved Ionic capitals, as well as the delicate torus decorations and elegant profiling of the few remaining original bases, explain its close—and on the whole very successful—Roman imitations. We have no difficulty recognizing capital C as an original piece, but it is hard to determine solely on the basis of style whether others, such as capitals A and D, are actually Hellenistic originals, or competent Roman copies (capital A is Roman, and capital D Hellenistic; see pp. 121-125).

The new ornament created for the east door—which might have been inspired by the ornament of the original west door, then moved on to the new Roman west wall—displays the persistent influence of specific Hellenistic models upon the common mid-second-century, Roman ornamental repertory of Asia Minor. In fact, the distinctive Hellenistic style or manner of the east door ornament may find signification and explanation through its links to the well-known classical qualities of Hadrianic ornament, though it also shows differences (discussed below). Compared to the refinement of the temple’s east door ornament, datable Hadrianic ornament from other sites often appears schematic and simplified.78 It is a pity that no Roman ornament of the exterior order survives to further illustrate this process of imitation and amalgamation.

Like an architrave would be, the jamb and lintel of the east door are divided into triple fasciae, separated by bead-and-reel and cyma reversa (Figs. 3.7, 3.8, 3.9). The crown molding is composed of a bead-and-reel and an egg-and-dart ovolo (pointed darts), surmounted by a strongly projecting cavetto decorated with open and closed palmettes alternating with lotus flowers. The cornice is composed of a small, plain cyma reversa crown and a plain corona projecting over a row of bold dentils, now partially preserved. No frieze has been found, though Butler restored one for reasons of completeness and proportion. The fine quality of the carving; the round, globular beads and their sharply outlined, disc-shaped reels; the well-formed eggs deeply set in their smoothly curving casings; and the overall superb modeling and plasticity led Butler to date this ornament to the fourth century BC, which was part and parcel of his efforts to see the building as a creation of the Classical era.79 Butler’s aesthetic assessment is understandable, yet the overall appearance of the jamb ornament is distinctively Roman

Compared to the eggs with slightly pointed ends encased in tightly fitting, narrow shells and delicate darts, all shallowly modeled, as is typical of late Hellenistic ornament of Asia Minor (as in the Hermogenes-designed Temple of Artemis at Magnesia on the Meander [Fig. 3.10] and the architraves of the Belevi Tomb near Ephesus), the egg-and-dart ornament at Sardis is deeply carved and strongly modeled, with more rounded eggs set in widely splayed and fully formed shells (Fig. 3.9). Although it displays greater stylistic affinity to the architrave ornament from the Smintheion at Chryse (Gülpınar), as compared to the thin precision and linear delicacy of its egg-and-dart crown (Fig. 3.12), the Sardis ornament has greater plasticity.80 Interestingly, the regular, well-rounded eggs and the bead-and-reel row of the architraves of the Hermogenean Temple of Dionysus at Teos appear closer to Sardis: this may be explained by the Hadrianic date that can be assigned to a part of the temple’s entablature (Fig. 3.11). At Sardis the careful triple alignment of the palmettes, eggs, and the beads of the crown molding of the jamb, especially the superbly modeled, almost lacy palmette-and-scroll row of the top cavetto, may follow Hellenistic precedents, but the fullness of these appears more distinctive than typical Hellenistic examples, where the decorative elements are subtly, but somewhat weakly, merged into a whole (Figs. 3.8, 3.9; cf. Fig. 3.12).

Likewise, the rich leaf pattern of the open-and-closed palmettes appears sumptuous on the door jamb cavettos, setting them apart from their lean, linear, and delicate Hellenistic counterparts. The Lesbian cyma of the door, with its broadly splayed leaves, hardly appears in the Anatolian repertory before well into the second century AD.81 The same individualistic quality holds when the door ornament is compared to some early or mid-Imperial Roman examples. At Sagalassus, the architraves from the Julio-Claudian lower agora gate and the egg-and-dart of the Ionic capitals from the Temple of Apollo Clarios (whose different phases are variably dated from the late first to the early second century AD) display the same delicate but shallow carving style, especially their flattened eggs with pointed ends; this is noticeably different from the precision of the Artemis temple’s east door ornament, whose aesthetic impact is enhanced by the changing play of light on its deeply recessed, three-dimensional surfaces (Fig. 3.13).82

Apart from these distant late Hellenistic/early Roman comparisons, a closer and more immediate model for the robust plasticity of the east door ornament comes from the original Hellenistic anta capital of the temple, especially when one compares the egg-and dart of the door jamb with the full, rounded, and articulated crowning egg-and-tongue of the anta capital cornice, now preserved on the southeast anta pier; this comparison perhaps illustrates the elusive concept of “Hadrianic classicism” in the plastic arts (cf. Figs. 2.293, 3.8).