Report 7: The Temple of Artemis at Sardis (2020)

by Fikret Yegül

Chapter 1. Introduction

Introduction

The Temple of Artemis at Sardis is the fourth-largest Ionic temple of the classical world and one of the most impressive in its natural setting (Fig. 1.1). It is situated outside the city in an extramural sanctuary on the western slope of the Acropolis, below the mass of the Tmolos Mountains, in a broad valley opening onto the Pactolus riverbed and beyond, toward the Hermus River plain to the north and northwest (Fig. Plan 1).

It is widely believed that construction of the colossal temple started soon after the Seleucid occupation of western Asia Minor began in the early third century BC. The temple was functional at least by ca. 250–240 BC, but it was not completed beyond the marble cella. The next major building activity commenced during the Roman Imperial period, probably around the time of Hadrian in the mid-second century AD; work on the peripteral colonnades continued over a long period of time, but it was never finished. It was during this Roman phase that the cella was divided into two chambers in order to incorporate the imperial cult. Although this preeminent religious center of Sardis was rooted in the worship of Artemis, the sanctuary, which long predated the temple, was the repository of many ancestral cults, overlapping protean beliefs, and sacred traditions throughout its pagan life (Fig. Plan 2).

Like the other two Artemisia of Asia Minor—the great Archaic/Hellenistic temple at Ephesus and the Temple of Artemis Leucophryene at Magnesia on the Meander—the principal facade of the Sardis temple faced west (Fig. Plan 6). Although extensive investigations revealed no earlier temple on the site, the area was sacred to Artemis (and probably to Cybele/Kybebe, too) from its earliest days, as attested by a Lydian altar (LA 1) datable on ceramic evidence to no earlier than the late sixth, but possibly the late fifth or even the early fourth century BC (Fig. 1.2).1 This structure, located at the west end of the temple, was replaced by a much larger Hellenistic altar (LA 2), to which the temple might have been intended to be physically connected (Fig. Plan 3; see below).

The temple is relatively well preserved in its overall structure (Figs. 1.3, 1.4, Plate 4, Plate 8-13). Of particular significance are the clear construction details and masons’ marks that illuminate the building process and changing construction characteristics over time. The unfinished details alongside the finished ones are particularly useful in illustrating the stages of construction. Although not entirely consistent, the recording and study of these details not only benefit the study of this temple but also offer a laboratory for the study of Greek and Roman architecture in general. Yet certain portions—such as the west end, the north and south peristyle colonnades, and the roof structure—are entirely gone, were altered, or were never finished. There is a single, intact architrave and two fragmentary ones, but none of the frieze, cornice, or the hypothetical pediment. Finely made roof tiles in marble of both flat and imbrex cover types found in large quantities indicate that the building was wholly or partially covered by a fine roof, whose valuable tiles were undoubtedly repaired and replaced many times (see Figs. 1.14, 1.15).2 These repairs and renovations, some more substantial and involving partial overhauling of the wooden roof and marble roof tiles, must have been occasioned by the earthquake of AD 17, which caused extensive damage at Sardis and throughout the rest of western Asia Minor (see pp. 229-231).

Changes and renovations over the course of the building’s long history make an understanding of the original design and its successive renovations very difficult. Even in its last phase of construction, the Sardis Artemision, like the near-contemporary Temple of Apollo at Didyma, was largely an unfinished building but a functioning temple—an impressive marble cella with a concentration of peripteral columns at its east end, some on the west, and a few at a stretch along the long sides. Furthermore, it appears that the architecture of the Temple of Artemis of Sardis, commonly thought of as a pseudodipteros, was highly unorthodox compared to the typical late Hellenistic and Roman pseudodipteroi of Asia Minor, such as the Temple of Apollo Smintheus in Chryse-Gülpınar and the Temple of Augustus and Roma in Ankara. It is therefore hard to place in traditional categories of Greek temple design.

We do not know the name(s) of an architect or engineer behind this unusual Roman pseudodipteros. However, one “Dionysius, an architect from vine-rich Tmolos,” who was active in the mid-second century AD, is known from the epigraphic record; he was admired for his technical skills and honored in Patara with a statue (see Fig. 4.19).3 The possibility of linking a name to our temple is exciting, though not provable, and lingers in the mind (see pp. 246–247).

-

Fig. 1.1

Sardis, general view of the acropolis, Tmolos Mountains, and the Temple of Artemis (looking east). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. Plan 1

Urban plan of Sardis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. Plan 2

The Sanctuary of Artemis, Sardis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. Plan 6

Temple of Artemis, Sardis, state plan, drawn 1:100 (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 1.2

Temple of Artemis, general view, including altar in front, with acropolis and Tmolos Mountains (looking southeast). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. Plan 3

Temple of Artemis, Sardis, western end with Lydian and Hellenistic altars. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 1.3

Temple of Artemis, general view of east face (looking southwest). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 1.4

Temple of Artemis, general view (looking north-northwest, toward the Pactolus valley and the Hermus plain). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. Plate 4

Partially restored elevation of north wall and peristyle (exterior, looking south), drawn at 1:100; Partially restored elevation of north wall and peristyle (interior, looking north), drawn at 1:100; Partially restored elevation of south wall and peristyle (exterior, looking north), drawn at 1:100; Partially restored elevation of south wall and peristyle (interior, looking south), drawn at 1:100. (Reduced scale; large version here) (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. Plate 8-13

State plan, drawn at 1:20 (originally published in 6 sheets). (Reduced scale; large version here) (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 1.14

Marble roof tiles found in Butler excavation. (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, accession no. 26.50.10.)

-

Fig. 1.15

Marble roof tiles. (Sardis II.1, pl. V.)

-

Fig. 4.19

Inscribed statue base of architect Dionysius, Patara. (Courtesy H. İ. Işık, Patara Kazıları.)

Archaeological Investigations at the Temple

The earliest attempt to excavate the building was made by Robert “Palmyra” Wood, who visited the site in 1750 and uncovered column 16 in front of the northeast anta pier, which was then standing. In 1850, George Dennis, the British Consul in Smyrna (Izmir), made several trenches in the cella and discovered a colossal marble head, which has been identified as Faustina the Elder, wife of the emperor Antoninus Pius (r. AD 138–61), and is now in the British Museum (see pp. 193–199). In 1904, Gustave Mendel, representing the Ottoman Imperial Museum in Istanbul, dug two trenches, one down to the bases between the east front columns 5 and 6, and another on the south side of column 1, but he could not continue due to lack of funds.4

Proper, systematic archaeological excavations in the temple were undertaken from 1910 to 1914 by Howard Crosby Butler, a professor of architecture at Princeton University and director of the first Sardis expedition, which was funded by a private group of supporters called the American Society for the Excavation of Sardis. The results were published in 1922 and 1925 in the first two volumes of a planned series of publications by the Society (Sardis I.1, Sardis II.1, and a supplemental atlas of plates). Excavations at the temple started on March 29, 1910, and were essentially completed by the end of 1914; further work had been planned, but it was not realized due to the start of the Greco-Turkish War.5

George M. A. Hanfmann resumed the excavations at Sardis in 1958 under the aegis of the Harvard-Cornell Archaeological Exploration of Sardis. Between 1960 and 1970, Hanfmann undertook a partial study of the temple and its precinct, and some ten trenches were opened.6

Further small-scale excavations and sondages in the temple between 2002 and 2012 helped to clarify aspects of the building’s history and design; these were supervised by Nicholas D. Cahill, the director of the Sardis Expedition since 2008, and the author.7 Between 2010 and 2012, LA 1 and LA 2 were consolidated and restored to the condition in which they were first excavated, thanks to a grant from the J. M. Kaplan Fund. In 2014–2018, another project removed the damaging black biofilm from the entire temple, again funded by a grant from the J. M. Kaplan Fund. This returned the marble blocks of the temple to their original color and texture, and additionally revealed many details which had been obscured by the lichen and cyanobacteria.The majority of the photos in this book show the elements of the building after treatment, with the stones restored to their cream color.8 Outside the work of the Harvard-Cornell Expedition, the Temple of Artemis has been the subject of several scholarly studies, notably by Gottfried Gruben in 1961 and more recently by Wolfram Hoepfner and Thomas Howe (see p. 158).9

In 1987, the author began a comprehensive investigation of the temple under the directorship of Crawford H. Greenewalt, jr. (1937–2012), which continued under Cahill. Among the primary goals of this project was the complete architectural documentation of the building and its construction details (plan, sections, and elevations at 1 : 20 scale; and details at 1 : 10 and 1 : 5 scales), and partial or full reconstruction studies aided by aerial photography and digital technology.10 The close observation and recording of the building has resulted in new information to illuminate the complex and occasionally controversial construction history and architecture of the temple, confirming some existing theories, but in general, it has revealed a picture in certain ways different than previous hypotheses.11

LA 1 and LA 2

The following is a condensed account of some of the recent investigations undertaken at altars LA 1 and LA 2 in 2006 and 2007, following Cahill’s interpretation of the archaeological evidence (Figs. Plate 1, Plate 8-13).12 Past investigations, as well as our more focused work, especially in the north pteroma trench of 2010 (see below), did not produce any evidence for an earlier temple, but they did establish that the precinct was occupied at least as early as the late Lydian period (sixth century BC; Figs. 1.2, 1.12, 2.76, 3.31, Plan 6, Plate 8-13).13

The precinct of Artemis must have assumed its specific religious character as a sanctuary by the sixth century BC and continued through the fifth, as attested by the Lydian Altar (and the purple sandstone “basis,” as it was called in earlier publications, inside the cella; see Fig. 1.6). The altar (LA 1, fifth or fourth century BC) is a square, stepped structure of tufa/poros (at euthynteria level ca. 8.82 x 8.14 m at top level 6.80 x 6.10 m; top as preserved ca. *98.30).14 The orientation of LA 1 is virtually the same as the temple, its mid axis deviating only six centimeters south of the temple axis.

Later, perhaps in connection with the construction of the Hellenistic cella, LA 1 was encased within a larger rectangular structure (designated LA 2) and like the earlier altar, approximately aligned with the temple axis. It is built of purple sandstone and limestone blocks, some of them reused, and measures 10.74 x 21.22 m.15 LA 2 appears to have been repaired many times during the Roman period, probably explaining the mortared rubble patches and the thick stucco coating of its walls. It was approached from the west by a monumental, marble-clad flight of stairs facing the Acropolis, 14.50 m wide (top at *98.30, ca. 1.70 m below the level of the pronaos and pteroma; Figs. 1.2, 1.12, Plan 2, Plan 3). The foundation of a table-like structure in front of the stairs with iron rings, perhaps for tying sacrificial animals, strengthens the identification of LA 1 and LA 2 as altars.16

Erosional deposits of sand and gravel into which the lower courses of these altars were set appear to be the same kind found under the temple that washed down from the Acropolis. Cahill describes two important conclusions from the earlier and recent investigations at the altars:

First, at least the lower two or three courses of LA 1 (and probably the whole structure as preserved) were probably foundation courses always intended to be below ground ... This would explain the very coarse stone(work) ... the irregular shape of the structure ... and the lack of any evidence for a marble facing or plaster ... Second, the ground level [which had been naturally raised by erosional deposits] must have been artificially lowered about 1 m when LA 2 was built ... leaving an “island” of this alluvial deposit.17

A full, detailed, and systematic archaeological description of the physical remains of the temple is the subject of Chapter 2. However, a summary description of the building and the measurements of its main parts are provided below for easy reference, followed by a short review of the history of the temple and its afterlife.

-

Fig. Plate 1

State plan, Temple of Artemis, Sardis, drawn at 1:100. (Reduced scale; large version here) (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. Plate 8-13

State plan, drawn at 1:20 (originally published in 6 sheets). (Reduced scale; large version here) (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 1.2

Temple of Artemis, general view, including altar in front, with acropolis and Tmolos Mountains (looking southeast). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 1.12

Temple of Artemis, orthophotograph (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 2.76

North pteroma trench (2010), north wall foundations (looking southwest). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 3.31

North pteroma trench (2010), view of north wall and foundations (looking south). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. Plan 6

Temple of Artemis, Sardis, state plan, drawn 1:100 (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 1.6

Temple of Artemis, east cella with basis and east crosswall (looking southeast). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. Plan 2

The Sanctuary of Artemis, Sardis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. Plan 3

Temple of Artemis, Sardis, western end with Lydian and Hellenistic altars. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

A Summary Description of the Building and Its History

The Temple of Artemis, as preserved, is a pseudodipteros with eight columns at the ends and twenty along the sides. The western pronaos and the original opisthodomos (facing east) display prostyle porches with four columns in front and two in the returns (Figs. 1.8, 1.9, 1.12, Plan 6, Plan 7). Consequently, the side pteromas, as uninterrupted ambulatories, do not wrap around the ends uniformly, as is normal in pseudodipteral temples.18 The sides are the usual two, but the ends are (technically) three interaxial distances wide.

The columnar spacing of the flanks, uniform at 4.99 m, is considerably narrower than that of the east- and west-end colonnades, where interaxial spacing increases progressively from 5.31 (5.32) m at the corners to 5.45 (5.46) m, 6.64 (6.66) m, and 7.06 m at the center—a total axis-to-axis distance of 41.88 (41.91) m (Fig. 1.10, Plan 4, Plan 5).19 The columns of the Roman peristyle are 17.87 m high, including their bases and capitals, the height probably determined by that of the existing cella. Column sizes vary according to their positions, but the average bottom diameters are ca. 1.96–2.0 m. The overall dimensions of the peristyle are 44.58 (44.61) x 97.60 (97.62) m, or roughly 151 x 330 Roman feet (adopting a Roman foot of ca. 0.295–0.296 m).

The cella, measured from anta pier to anta pier, is exceptionally elongated at 23.0 x 67.51 m, a ratio of 1 : 2.9, which is an Archaic characteristic. The original cella interior (before it was divided by the later Roman wall) was 18.36 (18.40 at top) x 39.60 m; the divided east cella interior is 25.16 m long; the west cella is ca. 26.74 m long.20 The walls are 2.13 m thick at the bottom and 1.93–1.94 m thick at the orthostat level. With these impressive statistics, the Sardis temple is not only the fourth-largest Ionic temple but arguably the largest pseudodipteros of the classical world.21

The base for the cult image, now preserved in sandstone foundation blocks, was placed centrally inside the cella (roughly 6.0 x 6.0 m and ca. 16.20 m from the Hellenistic west door; see Fig. 1.11, 2.79, 3.5, Plate 8-13). Cahill’s proposition that, along with the first altar (LA 1), the basis was a feature of the early sanctuary which was later enclosed by the temple is well taken. The need to include these important existing features may largely explain the tight positioning of the temple between the rising ground toward the Acropolis to the east and the large Lydian altar to the west. A double row of twelve columns inside the cella, also preserved only as marble foundation blocks, helped to reduce the span and support the roof (Figs. 1.12, 2.28, Plate 8-13). The center-to-center distance (north–south) between these interior column rows of the cella is 9.30–9.40 m, which gives a clear span of about 6.70 m, probably roofed by a wooden truss though double solid-section beams which could have done the job.22 The distance between their centers and side walls (aisles) is ca. 4.50 m. The center-to-center spacing between columns (east–west) is uniformly 5.40 m; the distance between the centers of the end columns and the cella end walls (west or east) is ca. 6.30 m. The reconstructed axial distance between the columns inside the west pronaos porch (columns 77–78 and 79–80) is ca. 8.40 m; the same distance is interpolated and reconstructed for the two hypothetical in antis, columns of the east end. The distance from their centers to the face of the anta walls is ca. 4.85–4.87 m (the same distance to the inner faces of the anta piers, which project inward by ca. 0.20 m, and is then only ca. 4.60–4.65 m).

The cella floor, originally paved in marble blocks, was ca. 1.60–1.70 m higher than the surrounding ambulatories and porches. The middle part of the floor between the rows of columns was 0.16 m lower than the sides. The original front pronaos (west) between the antae is ca. 17.98–18.0 m wide (north–south) by 17.70 m deep (east–west); the opisthodomos (east) is 18.0 m (north–south; measured inside the anta walls, it is 17.60 m, between the anta piers, which project in by ca. 0.20 m) by 6.01 m (east–west). The east pronaos porch (Roman era), defined by six columns, occupies an area of 23.01 m (north–south) by 21.05 m (east–west), creating very large spans of ca. 18.50 m (north–south) and 18.85 m (east–west). The side ambulatories, or pteromas, measured from wall to column base plinth, are 8.23 m wide (ca. 10.87 m, including the colonnade); the ends, measured east–west from anta to plinth base of exterior columns, are 12.40 m (15.05 m, including the colonnade or measured to the exterior of the plinth). Careful measurements made at foundation and plinth levels reveal a distinct curvature of the north, south, and east walls of the cella, although the full extent and consistency of these curvatures have been compromised by the settling of the foundations (Fig. 1.13; see pp. 55–57).

The original Hellenistic structure was limited to the all-marble cella covered by marble roof tiles (Figs. 1.14, 1.15); none of the columns of the peripteros were raised. In the Roman Imperial era, probably during the late Hadrianic or early Antonine period, the cella was divided into two equal chambers by the construction of a 0.90 m–thick wall to accommodate the imperial cult in one (east cella) and the goddess in the other (west cella). A new door, 6.08 m wide, was cut in the blank east wall that separated the cella from the opisthodomos, and stairs were built to provide access to the cella, whose floor was ca. 1.60–1.70 m higher than the floor of the porches (see Figs. 1.8, Plan 6, Plate 8-13, Plate 20).

During this period, major construction was undertaken to lay out some of the columns and column foundations of the peristyle colonnade. It appears that only the well-preserved columns of the east end, the east pronaos porch, and some or all of the columns of the west pronaos porch were completed. Only a few of the base foundations of the north and south flanks of the peristyle might have received columns, which are now gone, although the rough foundations of most of the columns were put in place. This represents the completion of 15 or 16 columns out of a total of 64 required by the pseudodipteral plan. Of the six columns of the west porch, the three columns of the southern half are preserved up to their finished upper foundation courses (columns 49, 53, and 54), so they could have supported columns above; columns 54 and 48 retain their base plinths.

The northwest corner column (52) is entirely missing—perhaps never built, or demolished and removed in later times. If this column was never built, the west front of the temple, nominally its principal facade, could not have had a proper facade during its Roman phase, even one without a pediment (unless the pediment was only over the cella, leaving the porch columns free-standing). However, these and the large numbers of fluted column drums found in this area suggest that the west pronaos porch had been, like its eastern counterpart, at least partially completed following the same design of the east pronaos porch.

With the exception of the southwest corner column (64), none of the exterior columns of the west peristyle were laid in, even as foundations. In contrast, the spectacular row of eight columns of the east peristyle (columns 1–8, of which columns 6 and 7 are preserved intact at 17.87 m) and seven more (six columns of the pronaos porch, 10, 11, 12, 13, 16, 17; and column 18 of the south peristyle) are preserved at different heights (see Figs. 1.7, 1.11, 1.16, 2.203).23 Celebrated in romantic images for centuries, these columns acted as beacons to early travelers and scholars and firmly mark the position of the temple and the city.

-

Fig. 1.8

East pronaos porch (looking northwest). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 1.9

Hypothetical pseudodipteral arrangement, as intended, without the roof, Roman era (looking west), digital reconstruction. (computer modeling, R. Pellegrini, UCLA Experiential Technology Center)

-

Fig. 1.12

Temple of Artemis, orthophotograph (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. Plan 6

Temple of Artemis, Sardis, state plan, drawn 1:100 (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. Plan 7

Temple of Artemis, Sardis, hypothetical composite plan, drawn 1:100 (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 1.10

East front and east colonnade (looking west). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. Plan 4

Temple of Artemis, Sardis, east porch survey and triangulation plan 1, drawn 1:100. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. Plan 5

Temple of Artemis, Sardis, east porch survey and triangulation plan 2, drawn 1:100. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 1.11

General view from the top of column 7 (looking west). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 2.79

East cella, column foundations 67 (left), 69 (center), 71 (right), with the basis and later foundation blocks (looking southeast). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 3.5

East cella, column foundations 69–71, and late foundation blocks with basis beyond them (looking southwest). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. Plate 8-13

State plan, drawn at 1:20 (originally published in 6 sheets). (Reduced scale; large version here) (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 2.28

General view with east colonnade, east porch, east door, and cella(s) (looking west). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 1.13

North wall with northeast anta pier, showing curvature (looking west). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 1.14

Marble roof tiles found in Butler excavation. (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, accession no. 26.50.10.)

-

Fig. 1.15

Marble roof tiles. (Sardis II.1, pl. V.)

-

Fig. Plate 20

Elevation of east wall (exterior, looking west), drawn at 1:20; Elevation of east wall (interior, looking east), drawn at 1:20. (Reduced scale; large version here) (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 1.7

South pteroma (looking east toward the acropolis). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 1.16

South pteroma, eastern end, with columns 6 and 7 and southeast anta (looking east). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 2.203

East peristyle with Church M at left. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

The Life and Afterlife of the Temple

It is believed that the construction of the temple started around 281 BC, within a century after the death of Alexander the Great, and achieved no more than the marble cella with its east- and west-end columns in antis, until the early to mid second century AD, when major construction in the temple recommenced and followed a pseudodipteral arrangement. Starting with its unbuilt peribolos, and the east and west prostyle porches, two nearly equal chambers were created by dividing the Hellenistic cella and the eastern part of the west pronaos to accommodate the imperial cult in the east one and the venerable goddess in the west (Figs. 1.12, Plan 6, Plan 7, Plate 1, Plate 2). The gigantic structure was still unfinished at the end of the fourth century AD. Yet, the continuing process and progress, though slow and messy, must have served as visual confirmation of the continued life of the temple and the community’s devotion to its principal religious icon. The ultimate (but unrealistic) goal of finishing a project of this size and complexity was mitigated by the visible and movable goal of continuing its progress, ever closer.

The cult of Artemis at Sardis appears to have its Archaic origins in Ephesus (see pp. 205–206). In ca. 560 BC, Croesus famously dedicated several columns in the Temple of Artemis of Ephesus, distinguished by their sculpted reliefs on tall, cylindrical pedestals.24 There are numerous references to the Ephesian Artemis at Sardis in Lydian inscriptions (Gusmani 1980, nos. 2, 23–24, 54). There is even mention of a golden figure of Artemis brought to Sardis from Ephesus for a feast celebration, although this appears to be a reference to an unknown Artemis sanctuary on the Gygean Lake (Lake Coloë).25 More specific is a late fourth-century BC inscription from Ephesus (inv. no. 1631, the “Sacrilege Inscription”) which records the death penalty for forty or more Sardians for attacking a sacred embassy (“sacred objects they profaned and sacred messengers they assaulted”) which was in procession according to ancestral custom (κατὰ τὸν νόμον τὸν πάτριον) from the Artemision of Ephesus to that of Sardis, which “was founded by the Ephesians.”26 Whether this means that the temple at Sardis was a “branch of the Ephesian cult . . . (of the) ‘Mother Church’ of Artemis Ephesia,” as Hanfmann claimed, should be viewed with caution, although connections between the two Artemisia, at least in their earlier stages, are certain.27 As E. Dusinberre commented, “we see the export of a cult” from one site to another, though Artemis at Ephesus and Artemis at Sardis unquestionably represented different aspects of the same goddess and different modes of worship.28 The question might be asked, then, if these forty-odd transgressing Sardians, coming from very different ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds, were simply close-minded religious conservatives who were jealous of the presence of a “foreign” cult in their Artemis sanctuary and represented a sentiment of broad intolerance, which Saint Paul, who was chased out of the theater while preaching Christianity there, must have known about.29 The Sardian cult of Artemis was certainly the primary religious belief at the sanctuary, lasting through the period when the great temple was shared by the Roman imperial cult upon the awarding of the city its second neokorate in the second century AD. However, the sanctuary continued to be a sacred ground that welcomed a variety of ancestral beliefs, though none was more important than the overlapping cults of the goddesses Cybele/Kybebe and Artemis with their subtly protean, inclusive, and changing identities. I propose a revision of the view that privileges the sole presence of Artemis in the temple and sanctuary and hope to introduce a more inclusive understanding of the syncretic relationship between Artemis and Cybele, as supported by wide-ranging contextual evidence from Sardis and Asia Minor (for fuller discussion, see pp. 207–212).

For centuries, between the completion of the Hellenistic cella sometime in the early third century BC and the major Roman rebuilding in the second century AD, Artemis’s temple existed as a precious marble box lightly raised on a podium; there was no peripteral colonnade, and possibly no paved pteroma. Yet it might seem contrary to our contemporary sensibilities that the marble box of the cella was perceived to be sufficiently “complete” to make it a proper templum. The continuing work (however intermittent) underscored the community’s piety. But, most importantly, the power of a Greek temple, even an unfinished one, resided in the grandeur and sanctity of its setting, the irreducible quality of the land it was a part of. The power of this geography, its timeless, hallowed nature, is one of the most notable aspects of the Temple of Artemis of Sardis, one that invests modern visitors to the site with a sense of awe. The Sardian landscape, with its craggy mountains, corrugated heights, and crumbling vales, evokes distant memories of Kybebe, and of Artemis, daughter of Zeus, Lady of Wild Things and “the goddess of the pointed hills.”30

Construction must have slowed down through the third century AD and been reduced to the addition of a column foundation or two along the long peristyles while pagan worship continued. Although the pseudodipteral scheme adapted by the Roman builders represents a creative interpretation of this system, the overall design (including the peripteral column height at 17.87 m) was based on recognition of the original Hellenistic building. The appeal and function of Artemis’s cult and temple must have diminished and ceased over the course of the fourth century AD, though the history of anti-pagan policies of the late Roman emperors, with periods of severity followed by tolerance, is too complex to relate here.31 Some of the temples were closed and pagan images plundered late in Constantine’s reign, while others enjoyed some measure of acceptance; intolerance and destruction continued with greater fierceness under his son Constantius.32 Anti-pagan policies and sentiments gained greater momentum and universality under Theodosius I with the Theodosian Decree of AD 391.33 Given this variable history of acceptance and rejection, it is logical to expect that some ad hoc form of pagan worship might have continued at the temple over the course of the fourth century; perhaps even the imperial images were tolerated, if not worshipped as divine objects.34

Dated by numismatic evidence to ca. AD 400, a small church (Church M) was built on the southeast corner of the temple.35 By that time, the imperial cult altar, which we hypothetically place somewhere at the new east front of the temple, would have been dismantled (see pp. 216–217). The main door of the church opened directly into the south pteroma of the temple between columns 7 and 8, its marble threshold at *101.30, ca. 1.30 m above the pteroma level. At a distance of 25–26 m from the temple’s east front, a pair of small, monolithic limestone columns (ca. 2.60–2.70 m high) standing on simple bases might have served as a kind of entryway (Figs. 1.3, 1.4, 1.12, Plan 2).36 Judging by the many Christian crosses carved upon the interior walls of the south anta and on the thick marble jambs of the east door, it is likely that the whole east porch of the temple might have also functioned as a kind of “atrium” for Church M (Figs. 2.41, 2.42).

Beyond this it is hard to document accurately the topography around the temple and the burial of the building by successive floods and landslides of gravel and silt down from the Acropolis, many of these probably associated with major events like the earthquakes of the early seventh century AD. Several geologists who have studied the topography around and under the temple agree that much of the east end was covered by the ninth century, which must have also marked the end of Church M.37 Butler remarked that by the end of the sixth century “soil had risen from 30 to 40 centimeters at the northeast angle and all along the north side of the temple,” and by this time extensive destruction of the temple had begun. Beside the broken blocks of the cella wall “lay some chisel-like tools of iron . . . and under a large block . . . was a sack of 216 coins dating between the years 569 and 615.” The temple was being used to a large extent as a quarry for good stone, with looters even digging out the foundations of columns not encased in rubble, although mortared rubble deposits were also coveted as easily reusable building material. Butler suggested that human occupation in the temple ceased from the seventh through ninth centuries, since no coins dating between AD 668 and 867 were found in the bottom meter of silt covering the east end, “while coins of succeeding centuries from 867 to 1400 AD were all found on the higher levels.”38 Unfortunately, much of this speculation cannot be checked against excavation reports and stratigraphic records because none was left.39 One assumes that such destructive activity spread over centuries would have also included mutilating and, in some cases, burying the colossal imperial images. Later, some humble occupation of the east porch with its better-preserved columns (square or rectangular holes—apparent beam holes—were carved on their shafts for the construction of makeshift shelters and roofs) must have continued.

Not all dismantling activity should be seen as sheer vandalism, as demolition was often an orderly process of deconstruction or a process of salvage for future construction in antiquity.40 We would benefit here from considering, or re-considering, the subject of spolia as a positive and rational choice for re-creating from old: sensible from an economic point of view, but often also projecting a sense of continuity and symbolism—its multivalent nature subsuming the physical and the symbolic, undoubtedly contributing to its cogency.41 The fine ashlar fabric of the temple and its many columns provided an economic opportunity for reuse and recovery. The Roman building probably provided resources for future buildings in and around Sardis, just as many fine ashlar blocks from earlier structures at Sardis had found a second life in the walls and foundations of the Hellenistic cella. Most of the walls and columns that were dismantled and broken, if not used as material in other buildings, were simply fed to lime kilns from the fourth through the seventh centuries, as the discovery of masses of marble chips, iron tools, and Byzantine coins indicate. There was also copious evidence for lime kiln activity in the upper levels belonging to the later periods, some as late as the nineteenth century.42 During the late antique and Byzantine era (fifth to thirteenth centuries) the land around the temple, especially to the northwest, became a residential area (Figs. 1.2, 1.4, Plan 2).43

For a useful, though spotty architectural description of the temple from the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries, we are lucky to have the descriptions and drawings of a number of early Western travelers, from Cyriacus of Ancona to Francis Bacon of the Assos excavations.

-

Fig. 1.12

Temple of Artemis, orthophotograph (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. Plan 6

Temple of Artemis, Sardis, state plan, drawn 1:100 (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. Plan 7

Temple of Artemis, Sardis, hypothetical composite plan, drawn 1:100 (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. Plate 1

State plan, Temple of Artemis, Sardis, drawn at 1:100. (Reduced scale; large version here) (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. Plate 2

Partially restored composite plan, Temple of Artemis, Sardis, Hellenistic and Roman phases, drawn at 1:100. (Reduced scale; large version here) (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 1.3

Temple of Artemis, general view of east face (looking southwest). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 1.4

Temple of Artemis, general view (looking north-northwest, toward the Pactolus valley and the Hermus plain). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. Plan 2

The Sanctuary of Artemis, Sardis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 2.41

East door, north jamb, graffiti. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 2.42

South wall of east porch (interior face), detail showing crosses and Christian graffiti. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 1.2

Temple of Artemis, general view, including altar in front, with acropolis and Tmolos Mountains (looking southeast). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

Description of the Temple of Artemis by Early Travelers

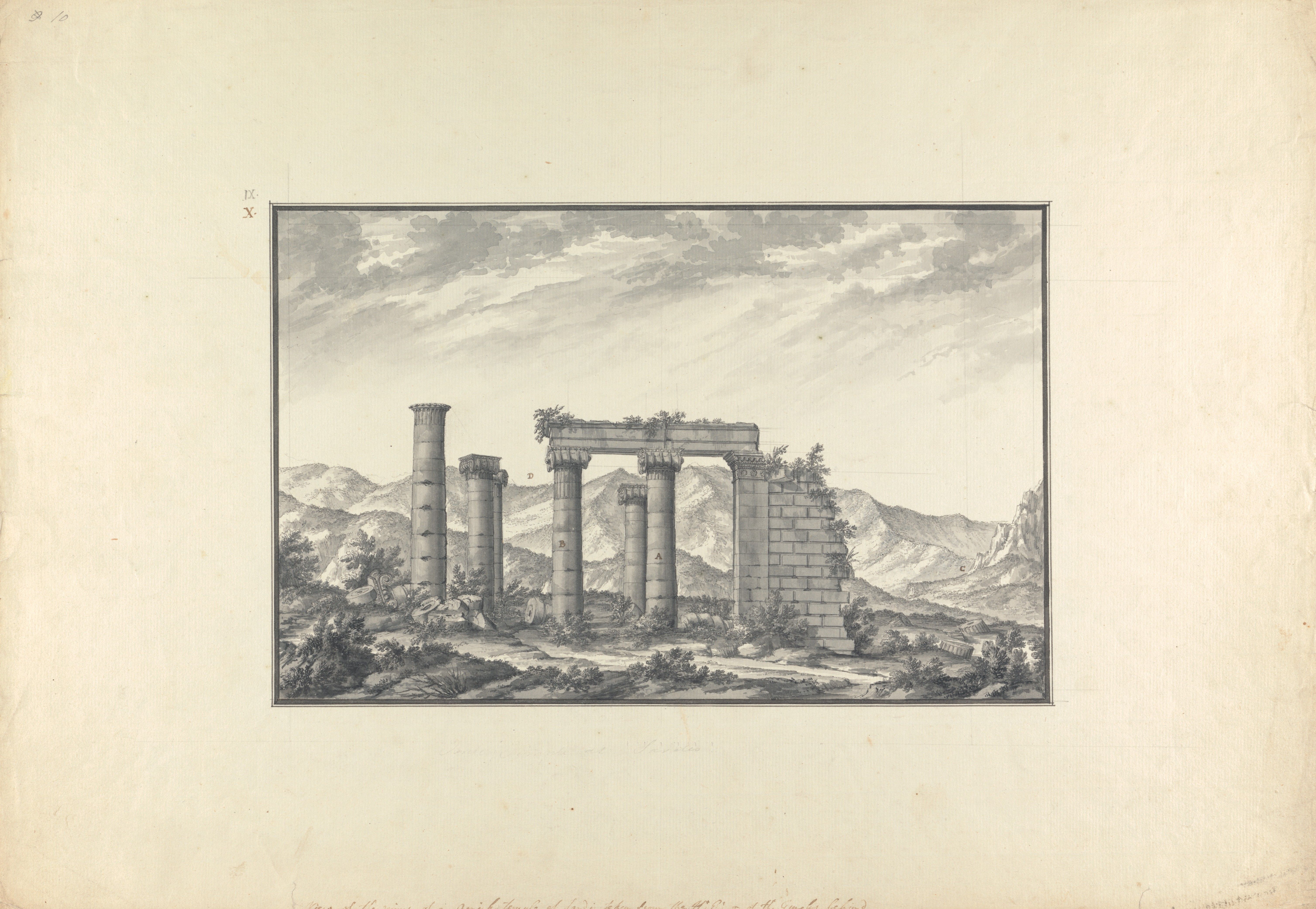

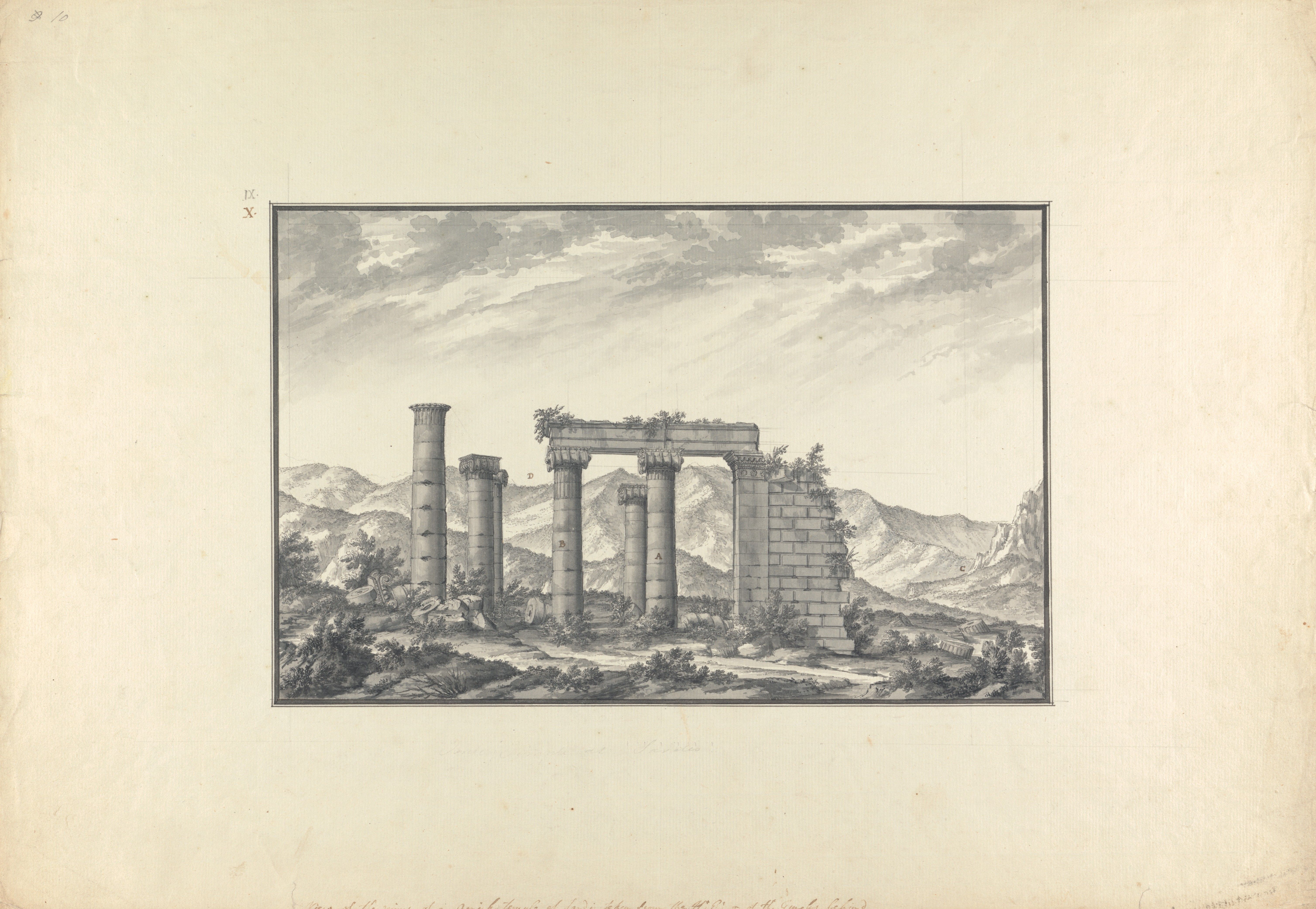

From the fifteenth to the beginning of the twentieth century—when the temple was systematically excavated by the American Society for the Excavation of Sardis under the directorship of Howard Crosby Butler of Princeton University—some ten or twelve travelers from western Europe are known to have visited Sardis and left an exceptionally valuable record of their observations in the form of narrative descriptions as well as sketches, watercolors, and measured drawings of major architectural features of the site. Since the Temple of Artemis was the preeminent classical monument of Sardis, and arguably the most impressive, with many of its well-preserved columns soaring 10–14 m above the ground, it was invariably included as a centerpiece in their descriptions and graphic recording of the ancient city.

Many visitors commented on the extraordinary beauty of the temple and its marble ornament, especially its elegantly carved Ionic capitals; none questioned that this was anything but the finest Greek work. Some of the travelers, such as Robert Wood (1750), were eminent classicists, antiquarians, or archaeologists; others, such as Charles Robert Cockerell (1812), were important architects or architectural historians whose later work preserved echoes of their careful study of the temple. Among picturesque sketches and watercolors were drawings that included measured plans, sections, and construction details. Robert Wood (1750), George Dennis, the British Consul in Smyrna (1882), and Gustave Mendel of the Ottoman Imperial Museum in Istanbul (1904) conducted limited excavations mainly to uncover the floor plan of the temple or determine the height of its columns. A careful study of these early drawings and descriptions thus is valuable because they not only illuminate the later history and destruction of the massive structure but also provide critical information about its overall design and construction details before destructive events, both natural and human, made their archaeological recovery impossible.44

It should also be noted that the accounts presented below represent, on the whole, the views of a scholarly and artistic cadre who displayed exceptional motivation to report and record the site. Among many other sites, Sardis thrilled some and disappointed others, but this group is balanced by other individuals who had an unrealistic idea of what to look for and find in a ruined ancient site and thus were disappointed by what they saw, spending scant time there. In 1840, the French historian Baptistin Poujoulat spent only a little time at Sardis, although he admired the two standing columns of the temple and described the architectural elements (including cornices) strewn about the site.45 This is a surprising attitude given that many of these travelers, even educated ones, spent many days or weeks on the road and overcame considerable hardships to reach their destination. For Enoch C. Wines, an American clergyman and prison reformist who visited Sardis shortly in 1832, the ancient site consisted of “principally undistinguishable masses of rubbish.”46 M. Greenhalgh’s comments on the subject are well taken: “[a] possible reason for some of the rushing on the part of the more educated travellers was that the aesthetics of the mostly Roman sites sometimes jarred, because they had been schooled to find Greek architecture pure, and Roman architecture decadent and inflated.”47 This is very much the direction Butler leaned toward and a sentiment, to a certain extent, still alive and well.

Cyriacus of Ancona

Cyriacus of Ancona visited Sardis in April 1444—nine years before Constantinople was conquered by the Ottoman Turks—which he recounted in a letter in Latin written from Foglia Nuova (in Genovese usage; the modern Yeni Foça on the western coast of Turkey) to Andreolo Giu-stiniani in Chios. Having seen the ancient remains of the royal city of Croesus, he singled out the Temple of Artemis as an exceptionally striking monument and described it as “an extraordinarily elegant wall belonging to the impressive temple of Sardian Jove, and surviving to our own day, twelve round, huge columns 45 feet tall and 15 feet in circumference, standing in their [original] positions.”48

Cyriacus’s assumption that the temple was dedicated to Zeus was quite logical, since he had found and copied an important dedicatory inscription at the site honoring a priest of Zeus Polieus, dated ca. AD 150.49 Another stele found in 1914, some 35 m northwest of the temple and dated ca. 100 BC, mentions the “worshippers of Zeus” and the sanctuary again.50 These inscriptions supported the early opinion that Zeus and Artemis were jointly worshipped at Sardis (and in the temple), predating the Roman imperial reorganization and reconstruction of the temple.

Although we do not know exactly which walls and columns of the temple Cyriacus saw (we have no surviving drawings of Sardis by him), it is natural to assume that he was referring to the better-preserved east end and the northeast and southeast anta walls, standing up nearly or certainly (in the case of the northeast anta) to their full height (for the numbered column designations described by travelers, see Figs. Plan 6, Plan 7). These are also the walls reported and recorded by many of the travelers who succeeded him. The twelve columns in their original positions (suo ordine intactas) probably had their capitals, and many had their architraves in place. This is twice as many standing columns as recorded by Thomas Smith in 1670, Edmund Chishull in 1699, and Robert Wood in 1750.

Since Cyriacus did not specify which columns he saw nor describe the order of their arrangement, we have no way of knowing where these six extra columns were. He probably saw intact the great majority of the columns of the east end that were ever built. We should not expect accuracy in Cyriacus’s assessment that the true height of the columns was 45 feet (13.7 m) and their circumference 15 (4.6 m; this was the height visible above ground; the total height of columns is 58 feet and 7 inches [17.87 m] and the circumference is close to 20–21 feet [6.1–6.4 m]). Therefore, the columns must have been buried approximately 14–15 feet (4.3–4.6 m), revealing three-quarters of their height. When Wood visited Sardis some three hundred years later, the ground had risen 30 feet (ca. 9 m), almost certainly the result of landslides from the high ground to the east burying the columns up to nearly one-half of their total height. We can also guess that Cyriacus saw the temple almost half intact on the eve of its wholesale destruction by lime kiln operations and the alleged (not verified, but logical) use of its marble blocks in the construction of Manisa’s fine Ottoman monuments, especially the mosque built by Murad II around 1443.51

Thomas Smith (1670) and Edmund Chishull (1699)

Thomas Smith, chaplain to the British Embassy in Constantinople, came to Sardis in 1670 and found only six columns fully standing; thus, the temple had lost six columns over the two centuries since the visit of Cyriacus.52

These were clearly the six columns seen and described by Robert Wood and his party in 1750 and also identified as the “east portico” columns by Edmund Chishull, another British chaplain in Smyrna (Izmir), who visited the site in 1699. From the evidence of his later drawings of these columns, Chishull must have seen three columns from the east colonnade: columns 6, 7 (today fully standing), and 1, the extreme north column; and two in front of the northeast anta pier, columns 16 and 10; and column 17, in front of the southeast anta. The capital of column 6 was already displaced. Chishull also mentioned the two intact anta piers and the great portal, an impressive sight with its lintel still in place, “a vast stone which occasioned wonder by what art or power it could be raised.”53

Aegidius van Egmont and John Heyman (ca. 1725-50)

In the second quarter of the eighteenth century two Dutch travelers, Aegidius van Egmont and John Heyman, visited Sardis, among other sites in the Mediterranean, and they published their travel accounts in 1759. They saw the six columns still standing to about 20 feet above ground (ca. 6 m), intact with their capitals except for one, whose capital had fallen (column 1); the displaced capital of column 6 was referred to as “mutilated.” Their description of the state of preservation of the pronaos porch is significant: “On two of these pillars, and the remainder of a frontispiece, was a transverse stone, of such enormous weight, that it is difficult to conceive how it was possible to be placed at such a height.”54 The “frontispiece” must have been the northeast anta pier, and the “transverse stone” the two lengths of architrave in place spanning the spaces between column 16, column 10, and the northeast anta. There is no mention of the portal, which must have fallen by the early 1700s. The Dutch travelers saw columns 6, 7, 1, 17, 10, and 16. They do not mention an architrave between columns 6 and 7.

Robert Wood and His Team (1750)

The well-known English classicist and traveler Robert “Palmyra” Wood and his party of four visited Sardis between May 27 and June 2, 1750, on the way to Palmyra and Baalbek in Syria. Besides Wood, there were John Bouverie (an archaeologist) and James “Jamaica” Dawkins, both Oxford graduates; the fourth member was Italian draughtsman Giovanni Battista Borra, whose sketchbooks, with many overall views and details of the temple, contain the first known graphic representation of the building.55 Other members also kept diaries or notebooks: Wood on topography, antiquities, and inscriptions; Bouverie on the monuments and archaeology; Dawkins mainly on anthropological subjects, flora, and fauna. These records, and their later transcriptions, are preserved in the Joint Library of the Hellenic and Roman Societies at the Institute of Classical Studies in London.56

Bouverie’s account of the temple’s east porch is detailed and informative: “Six pillars [columns] remain upright, all save one with capitals [which are] wonderfully sharp and well preserved… Two of those are joined by the architrave to a Pilaster [anta pier] and a bit of wall which serves to show the way the body of the temple [its cella] ran.”57 This description agrees with Borra’s ink and wash drawing of the temple, now in the Yale Center for British Art (Fig. 1.19), which was based on a pencil sketch probably made on site in his sketchbook (Fig. 1.18). The drawing shows the east porch from the northeast as it appeared at the end of May 1750. The columns shown are numbers 1, 6, and 7 on the east front (the first three columns on the left); numbers 10 (designated “B” in Fig. 1.20) and 16 (designated “A”) carry two lengths of the architrave spanning between them and the fully intact northeast anta pier; and number 17, the column directly in front of the southeast anta, is shown in the distance between the latter two.58 The ordering of the eight columns of the east front in the Borra plan (Fig. 1.20) corresponds to their positions indicated later in Butler’s plans (Fig. Plan 6). The capital of column 1, the only one not in place, is shown upended at the foot of the column; the capital of number 6 is askew, as it is today (see Fig. 2.203, 2.245).

The columns in the drawing are uniformly preserved for nine or ten courses (drums) above ground level, or about half their total height. When Butler started the excavation of the temple in 1910, the ground was 1.5 m lower, perhaps the result of erosion but more likely from illicit digging for the temple’s coveted marble (Fig. 1.17). It is also interesting that the top drums of all columns (and the top two drums of column 10) are fluted, not just those of columns 6 and 7. Noticing this and other details, Bouverie had rightly concluded that the temple was unfinished: “Under the capitals which are of the finest taste and most excellent workmanship the shafts are channeled [fluted] about a foot downwards. . . . One of them nearly 3 feet [fluted on top] and left plain in the form of a pillar [an unfluted shaft] but rough chiseled which would be quite irregular if intended to remain and has a disagreeable effect.”59

Although Borra’s drawing is remarkably accurate, he took some liberties, varying his vantage point in order to provide a “maximum view” and reveal more features of the temple (Fig. 1.19). One such inconsistency, visible because Borra shifted his vantage point eastward, is of invaluable help to us: the east face of the architrave carried by column 10 (labeled “B”) reveals a profile molding of two fasciae and a simple crown molding, albeit at a very narrow perspective. This detail confirms that the projecting inner porch ended with column number 10—its northeast corner column—and therefore, the outside corners of the projecting porch were carried by regular Ionic capitals facing east–west like the rest of the capitals of the east porch, not special corner Ionic capitals as one would have expected.

A sketch plan made on site, where the surviving columns are shown as dark, cross-hatched circles (Fig. 1.20), and the written account, both in Bouverie’s diary, corroborate Borra’s drawing and indicate that Wood’s party had worked out the basic architectural arrangement of the porch quite accurately as an octastyle temple, though it is not certain that they had figured out that the plan was pseudodipteral. The sketch shows only the features they were able to ascertain (visible on the surface of the ground or verified by minor excavating); this included the six fully preserved columns (dark cross-hatched), the location of the east door, and the alignment of the east wall (dark lines). The measurements, given in feet, are incorrect. Columns barely above the ground (which do not appear in this view) are shown in a light hatching; and the hypothetical positions of the rest of the columns are delineated very lightly (some, like the two columns of the inner porch raised on high pedestals, numbers 11 and 12, are crossed out).60 It is interesting that neither the plan nor the drawing shows the southeast anta at all, though its existence was verified by a minor excavation around its presumed location.61 Clearly, in the half-century since Chishull had admired it in 1699, the great lintel of the east door had fallen and was probably buried—along with whatever was then visible of the southeast anta—since neither Bouverie nor Wood mention it (but Chandler saw and commented on its having fallen fifteen years later; see below).

It appears that the remains of the temple impressed and fascinated the group (“undoubtedly very ancient and of a good age … [and] the exquisite Taste of the Capitals and most excellent Workmanship induced Us to resolve [by digging] to get at the Members ”).62 They stayed an extra day in order to dig all the way down to the bottom of column 16 (east of the northeast anta pier, labeled “A” in the sketch elevation and “E” in the plan) and sketched what appeared to them to be the unusual Ionic-Attic profile of the base and the vertical leaf decoration of its torus. They measured the column correctly at a height of 58 feet 7 inches, which is what the current Expedition found by direct measurement of columns 6 and 7 in 1992 and 2019. This appears to be the first historically recorded excavation at the temple: “We dug down about 22 feet to discover the Base of a Pillar [column 16] which formed a good deal different from the regular Ionic Base, consisting of More Members and less Projection most likely to disencumber the spaces as much as possible. The upper Toro [torus] was adorned with scales pointed upwards.”63

Claude-Charles de Peyssonnel (1750)

Claude-Charles de Peyssonnel, a French diplomat in Smyrna, visited Sardis only a few months after Robert Wood, and he made a pencil sketch of the east porch of the temple from roughly the same angle as the Borra drawings (Fig. 1.21). The sketch, a more Romantic set piece with figures in toga walking the ruins and sketching (entitled “Vue d’un ancien Temple de Sardes”), shows only five columns (but both of the anta piers fully standing) and is generally consistent with Peyssonnel’s description: “There still remains of this temple five columns of the Ionic order. . . . They are about thirty feet high. The two middle columns support a cornice and architrave, which abuts upon a pier of an order approaching Doric [meaning the anta capital with its wreath and rosette decoration]. Towards the south are two other similar columns … and a pier exactly like the first [the southeast anta; my emphasis].” He further adds, “I observed a hole excavated in the earth at the foot of one of the columns which support the cornice [of column 16]. My guide told me that this hole had been made by an English traveler [Wood, of course], who had desired to find the depth of the column.”64

Peyssonnel’s sketch and description represent column 1 (with its capital fallen directly below, as in the Borra drawing), columns 6 and 7 (with their capitals but no architrave), and columns 10 and 16 carrying two lengths of architrave spanning to the northeast anta and a short stretch of the north wall. There is no “cornice” in situ; Peyssonnel might have confused the unusually heavy crown molding of the architrave for a cornice, and many nonspecialists referred to architraves and cornices indiscriminately, as Peyssonnel does in his second reference to a “cornice” on column 16. Disregarding some proportional inaccuracies in the Peyssonnel sketch, there are two important differences between his and Borra’s views; apparently in the two short months between the two visits, column 17, in front of the southeast anta pier, had been razed to the ground, except for what appears to be the top of its uppermost-preserved drum, seen barely above the ground upon which stand two figures. The second difference is more problematic; the southeast anta is shown fully preserved behind the northeast one including its pier capital and is described as “a pier exactly like the first”—i.e., like the northeast anta pier. How is it possible that Peyssonnel saw and recorded the southeast anta fully standing but Wood did not? Only Wood dug for it and ascertained its existence (“found a piece of the other pilaster fallen”). Are we to believe that the villagers of Sart reconstructed it after Wood and his party had left? One possibility is that Peyssonnel saw the position and well-preserved remains of the southeast anta (its anta capital still exists) that had been partially uncovered by Wood, and, knowing that it would be a mirror-image of the other, he made his sketch with the southeast anta restored.

Richard Chandler (1765)

Richard Chandler was authorized by the Society of Dilettanti to lead an expedition to Greece and Asia Minor from 1764 to 1766 in order to collect information about antiquities and record as many as were available.65 Other members of his team were architect Nicholas Revett (of Stuart and Revett fame) and William Pars, a talented young artist and draftsman. After spending some time in Athens, the party arrived in Smyrna in September 1764; using that city as a base of operations, they took several long trips inland and made many excellent drawings. They came to Sardis by way of Philadelphia (Alaşehir) sometime in late April or May 1765 and stayed no more than a day. They saw five columns of the temple (“five columns are standing, one without the capital; and one with the capital awry to the south”), the same as Peyssonnel but one less than seen by Wood. Chandler also mentioned Chishull’s account (1699) of the east door (“that fair and magnificent portal, as it is styled by the relater [meaning Edward Chishull]”) and added that the great lintel had fallen on a heap of debris and that “part of one of the antae is seen about four feet high.” Chandler then described an architrave: “The architrave was of two stones. A piece remains on one column, but moved southward; the other part, with the column, which contributed to its support, has fallen since the year 1699.”66 This must have been a fragment of the architrave that spanned from column 16 to the northeast anta pier seen and recorded by Wood and Peyssonnel. Obviously, in the fifteen years since Wood’s and Peyssonnel’s visits, column 10 and the northeast anta were demolished almost completely (though it was still some 10–11 m above the original pavement, of course). Since it had lost its supports on either side, this also means that the architraves spanning columns 10 to 16 (as shown in the Borra drawing; see Figs. 1.18 1.19) and from 16 to the northeast anta pier would have fallen. By referring to the architrave as “two stones,” Chandler must have meant that it was broken into two pieces, and only the fragment remained on “one column.” Since both the northeast anta and column 10 were no longer fully standing, we must imagine that a mere stub of an architrave end was left sitting on the capital of column 16 when Chandler saw it.

It is a pity that this important mission’s interest in the Temple of Artemis at Sardis was reserved for only a few hours, that they did no drawings (while they had spent days at Didyma studying, measuring, and drawing), and that their observations were restricted to a somewhat ambiguous textual description by Chandler. To our knowledge, of the 16–18 excellent watercolors Pars executed in Asia Minor (now in the collection of the British Museum, London), none represented Sardis; this is surprising because the Sardis temple in its exquisite setting became a very popular subject for many less-talented artists in the nineteenth century.67

We are lucky to have a fine but undated and unsigned watercolor representing the temple more or less as Chandler’s Ionian mission must have seen it.68 The view, with a caravan of camels in the foreground (comparable to the “numerous caravans” Chandler had seen near Sardis), shows five columns, all but one with capitals, dominated by the Acropolis in the background and the distant Tmolos range to the right (Fig. 1.22). Compared to typical “Sardeis views,” there is little to no dramatization of the landscape (which is dramatic enough as it is). Specific features such as the so-called “flying towers” salient of the Acropolis, or the prominent hill just behind the temple where Butler later constructed an expedition house, are correctly rendered (see Figs. 1.1 1.2). To the right (south) is a group of three columns: 6, 7, and 17 in front of them; on the left are two columns: 1, identified because it is the only column without a capital, and 16 in the foreground (the column in front of the demolished northeast anta pier) carrying a single, chunky architrave piece, closely matching Chandler’s description. This is a part of the architrave found later by Butler in three pieces, E, F, and G (see Fig. 2.312).

A similar recording of five columns, all with capitals except one, and one carrying a chunky architrave fragment (on column 16), is the subject of a fine watercolor by the French architect François-Michel Préaulx, who was active in Constantinople and Turkey between 1796 and 1815, entitled Vue du temple d’Artémis á Sardes (Fig. 1.23).69 These two watercolors must have been done sometime between Chandler’s visit to the site in 1765 and C. R. Cockerell’s visit in 1812, because Cockerell saw and recorded and described only three standing columns on the site (6, 7, and 16, see below).

Outstanding among these popular views of Sardis and the temple is a grand panorama of the temple painted by Danish landscape artist Harald Jerichau in 1878 (Fig. 1.24).70 The view shows the two columns of the temple, ruins, and a camel caravan, looking south to the exaggerated rise of the Acropolis and the snowy Tmolos Mountains. The artist has shifted the temple to the Hermus plain north of the city next to a small, swampy brook. Such composite collages of landscape for effect were not uncommon, as evident in English painter Harry John Johnson’s Sardis (1840s; not illustrated): another view of the temple from more or less the same location on the plain, looking south toward palm groves (which never existed) and mountains. Three columns of the temple are shown; there are fallen drums and one modillionated cornice in the middle of a swamp, with foxes hunting birds.71

C. R. Cockerell (1812)

Charles Robert Cockerell (1788–1863), a distinguished British Neoclassical architect admired for his “bold deployment of the orders and the beauty of his [classical] detail,” visited Sardis for two days in March 1812.72 He was twenty-four years old and on a Grand Tour of Italy, Greece, and Turkey from 1811 to 1817. His description of the temple (identified as “The Temple of Cybebe”) is known only from a letter he wrote to W. M. Leake, which appeared as an extended footnote in the latter’s Journal of a Tour in Asia Minor (1824).73 This publication also reproduces a sketch plan of the east porch (including some measurements in feet) and a partially restored elevation of the east facade of the temple made by Cockerell (Fig. 1.25). In addition, a handsome pencil sketch (now at the Yale Center for British Art, Fig. 1.26) shows the three columns of the temple preserved in 1812, down from the six recorded by Wood and Borra in 1750, the five recorded by Peyssonnel in the same year, and then by Richard Chandler in 1764.74 Cockerell’s drawing, a view of the east end of the temple looking southwest, clearly shows columns 7, 6, and a third column to the right (or north) of these, probably number 16 (the column in front of the northeast anta). Considering the angle and proportion, one would have imagined the third column to be number 17 (the column in front of the southeast anta); however, since this column did not stand after 1750 (it is shown as a stub on the Peyssonnel drawing) we are left to assume that it was number 16. It appears that Cockerell made his sketch from a spot on the rising Acropolis slopes east of the temple; he had a wide field of vision toward the south-southwest and he focused on the three eminent columns, much like looking through the telescopic lens of a modern camera. The inscription at upper right comments that the columns resemble those he saw in Athens in terms of color, white but with blue streaks in them, but that the capitals are “highly colored”—perhaps alluding to the strikingly yellow-ochre hue of the capitals resulting from the peculiar weathering conditions.

The Cockerell drawing, however, is inconsistent with his later published description of the temple quoted in a footnote in Leake’s Journal: “Two columns of the exterior order of the east front [columns 7 and 6], and one column of the portico of the pronaus [column 16], are still standing, with their capitals: the two former still support the stone of the architrave, which stretched from the centre of one column to the centre of the other.”75 In the sketch elevation of the temple’s east front, published by Leake (see Fig. 1.25), this architrave (labeled as “A”) is shown in situ tentatively, as if restored (much like the rest of the east front of the temple with a pediment; the nonexistent architrave in the middle intercolumniation is shown the same way, labeled as “B”).76 The Yale drawing (Fig. 1.26) has no architrave carried by any of the columns. Furthermore, none of the travelers who were in Sardis before Cockerell mention an architrave carried by the columns of the front row, or include it in their drawings; for example, neither of the Borra drawings, each of which has remarkable detail and includes an architrave supported by the porch columns 10 and 16, shows an architrave on columns 6 and 7 in the background (see Figs. 1.18, 1.19). Cockerell probably did see this architrave on the ground close to columns 6 and 7 (it was found intact in this location by Butler, described as architrave “A”), measured it, estimated its weight to be twenty-five tons, identified its position correctly as having spanned the columns, and then included it in his “restored elevation.” But, in the note he wrote to Leake ten or twelve years after his visit to the temple, he described it as if the architrave was in position. His fine drawing, always a better representative of an architect’s ideas than his words, is characteristically correct.77

Cockerell also observed that “besides the three standing columns, there are truncated portions of four others belonging to the eastern front, and of one belonging to the portico of the pronaus; together with a part of the wall of the cella.”78 Cockerell’s sketch plan and restored elevation (Fig. 1.25) show the “truncated columns” of the east front (numbers 2–5, cross-hatched); column number 1, which had been the best-preserved column of the east front for a long time, had completely disappeared by 1812 (Fig. 1.26). Since these truncated columns were barely at surface level in 1750, the ground must have dropped considerably to reveal at least small portions of their tops in the fifty to sixty years since the Borra and Peyssonnel drawings, likely due to feverish digging to obtain the temple’s marbles to cart them elsewhere or burn them for lime.

Did the massive columns and handsome capitals of the Temple of Artemis serve as models, directly or indirectly, for Cockerell’s later work? There is little question that the grand scale and exuberant decoration of the Ionic monuments of Asia Minor impressed the young architect and influenced his early work in a way that the more austere and small-scale examples from Greece did not. The Ionic order of the pedimented portico of the Hanover Chapel in London, 1821 (now demolished), was directly inspired by a mixture of Anatolian models, such as the Temple of Athena at Priene and the Temple of Apollo at Didyma; but more specifically Sardis is singled out by Cockerell himself as the outstanding example in his diary entry for April 29, 1821: “Upon the chapel New Street [Hanover Chapel, London] . . . hit upon the double pilaster to carry tower Portico . . . chose Asiatic Ionic not yet seen—the cap[ital]s of Sardis.”79

Anton von Prokesch (1824)

Anton von Prokesch reports that only two columns were standing when he was at Sardis; obviously, during the twelve years since Cockerell’s visit, column 16 had been largely demolished, leaving only the two famous columns, numbers 6 and 7. As noted by Butler, Prokesch’s local host (Turkish or Greek) had a lime-making concession in the temple, explaining the major part played by humans in the destruction of the temple from the earliest days and the copious evidence for lime kilns in and around the building found by Butler’s excavations.80

Clarkson F. Stanfield (1830s)

Clarkson F. Stanfield (1793–1867), an English commercial artist and scene painter, never went to Turkey; therefore, technically he should not be considered in this section devoted to early travelers to Sardis. Nonetheless, he was instrumental in producing one of the most detailed and interesting drawings of the temple around 1830, which appears to have been based on another competent drawing or sketch which was made on the spot by another yet unknown traveler or artist. Stanfield’s watercolor presents a view of the temple from the east, featuring the two standing columns on a stormy day and a frightened horse and fallen rider (Fig. 1.27). Littered in the foreground are many unfluted drums, whose construction details are correctly delineated, and one massive cornice with modillions. Everything appears to be as Butler saw it seventy to eighty years later in 1910; the two standing columns are intact but carry no architrave. Column shafts are preserved with twelve drums above the ground, so the ground must have been some 1.50–2.0 m lower than it was in 1750, when Borra could see only nine drums. Besides these two, the top of a column (next to column 6) appears above ground, probably number 5. The drawing, which Butler praised for its accurate details, is important because it shows in the distance a few truncated columns, probably fluted, not mentioned by any of the travelers except Bouverie, who, however, thought that they belonged to a different building because they were so far away (“toward the River lye several broken pieces of fluted Pillar but not enough to import that the Temple extended so far”). Indeed, these must have belonged to the columns of the west pronaos porch since Butler found many fluted drums in this location. But, even more importantly, in the foreground among the fallen column drums of the east colonnade there is a clearly delineated cornice with modillions, unmistakably of the Roman type. This represents the only possible evidence of a cornice belonging to the temple, and one, it seems, also noted by Poujoulet in 1840 among the temple’s fallen architectural detritus (see above).

Crawford H. Greenewalt, jr. observed that the Stanfield drawing was made, as were a number of other nineteenth-century views of Sardis and the temple, “for picture books aimed at readers primarily interested in historic or religious aspects of the site—for example, Sardis as one of the Seven Churches of Asia.”81 Stanfield’s engaging view appears to have been commissioned as an illustration for a two-volume publication called Landscape Illustrations of the Bible, with text by Reverend Thomas H. Horne, published in London in 1836; it was reproduced as an etching by the engraver William Finden as plate 45. However, its popularity ensured reproduction in a number of variant etchings and engravings.82 A watercolor at the Victoria and Albert Museum, which shows the same scene, has been tentatively identified as the original, made by one “Mr. Maude” (Fig. 1.28), from which Stanfield had copied and “improved” (or “jazzed-up”) his watercolor. As observed by C. Newton, a prints and drawings specialist from the Victoria and Albert, “Stanfield was a famous and highly-skilled resident scene-painter at the Drury Lane theater, so dramatizing the landscape [of the original Sardis drawing] came naturally to him.”83 That may be so. However, Stanfield’s illustration not only creates an appropriately apocalyptic image for the purpose, but it is also archaeologically accurate with many details specific to this temple, such as the fact that the tops of the column shafts are fluted; and the abacus of capital B is correctly shown terminated by a fillet (the only example at the temple), whereas that of capital A is not, none of which are shown in Mr. Maude’s rather humdrum and erroneous illustration (see Fig. 2.232). Therefore, even if Stanfield never saw the temple, he must have been working from a very accurate drawing made by someone who had been on site and who was skillful, knowledgeable, and observant of the temple’s unique details.

Charles Texier (1830s–40s)

The illustrious French archaeologist and antiquarian Charles Texier, author of the influential Description de la Asia Mineure (Paris, 1838–48), traveled in the provinces of the Ottoman Empire under the aegis of the French Ministry of Culture in the 1830s. His visit to Sardis occasioned his deep regret for the exceptional destruction of a beautiful site by human agency: “Aucune ville, à l’exception de Babylone, ne peut offrir un plus triste tableau de l’anéantissement de toute puissance humaine.”84 He identified the building as a temple of Cybele but wrote a fairly detailed and otherwise knowledgeable description, admiring the remaining two columns, the beautiful capitals, and the quality of its marble, and lamenting its ongoing destruction. Regrettably, he left behind no example of his skill in elegant (though not always accurate) drawings of historic architecture.

Francis H. Bacon (1882)

Francis H. Bacon, one of the leading members of the American team excavating in Assos (with J. T. Clarke and R. Koldewey), visited Sardis in April of 1882. In a letter dated September 18, 1882, Bacon wrote to Professor Charles Eliot Norton of Harvard University that he had visited Sardis, where George Dennis, the British Consul at Smyrna, was then excavating three of the smaller tumuli at Bin Tepe and planning to start excavations at the temple.85 Bacon saw the temple for a few hours during this hurried trip and admired the two fully preserved columns with their beautiful capitals and the truncated top of a third, standing on a smooth slope of green grass with nothing else around them, looking “very inviting to the excavator.” He did some sketches of what appears to be column 6 with its capital. Indeed, in his second visit to Smyrna during the same summer he saw Dennis haphazardly at work in the temple. Bacon described his second visit to the temple as an addendum to his letter to Norton: “Mr. Dennis has not begun to clear off the temple plan in a systematic manner, that would be an expensive affair. So far he has only dug pits and trenches, and the only thing he has found … is a beautiful colossal head, supposed to have belonged to a statue of Cybele [the head, identified as Faustina the Elder, is now in the British Museum; see Fig. 3.53]. He measured from the columns at the East, to where he supposed the West end to be, and ran a trench from there eastward, into the nass [sic; naos]. He found a terra cotta Roman pavement, and very few architectural fragments (but perhaps these may lie outside his trench). Just beyond the centre of the nass [sic], lying upon about a metre of debris, he found the colossal marble head lying face down . . . it is almost in perfect condition. . . . I did not see the head . . . only a photograph. It is entirely different from any Greek or Roman head that I have ever seen.”86 Bacon did not go back to Sardis to see more of Dennis’s excavations at the temple, and there is not much information about the architecture of the temple uncovered by what might be considered its first major but not methodical excavation. As far as we can judge, Dennis’s digging was rather a treasure hunt, and he probably kept no record of his fast excavations, nor did he publish anything. The exact find location of the Faustina head is also unknown; it was clearly “in the center of the naos,” though it was not specified whether it was the east or west cella. As Butler informs us, Dennis’s long trench and two pits were still visible when he began work in 1910.87