Report 2: Sculpture from Sardis: The Finds through 1975 (1978)

by George M. A. Hanfmann

Chapter 2. The Sculpture of the Prehistoric, Lydian, and Persian Periods. An Overview and Appraisal

Introduction

In this chapter we will attempt to draw together some of the results suggested by our study of the sculpture of the Lydian and Persian eras found at Sardis and to integrate the works of stone we have collected into a framework of stylistic development as it is beginning to emerge from the data of the excavations at Sardis, from comparisons with Sardian sculpture in other media, and from a view of the artistic developments in the neighboring regions. The pieces we survey span about three centuries, from the late seventh to the late fourth century B.C. Although not numerous and often fragmentary, they yet permit a delineation of some stylistic, iconographic, and social aspects of sculpture in the times of the Lydian kings and Persian satraps when Sardis served as a clearing house in trade and ideas between the Mediterranean world and the Near East.1

Sardis, at least at the time of the Lydian kings Alyattes and Croesus, seems to have harbored an important school of sculptors. Subsequently under the Persians it may have been a focal point in the formulation of the “Greco-Persian” art created for the satrapal courts. We are now in the position to point out interesting stylistic relationships with the “Late Hittite” Anatolian areas, with workshops in Eastern Greece and on the Greek mainland, and later with Iran; and we can at least pose, if not completely answer, the question of what specifically Lydian traits may be discerned in Sardian sculpture.

What sculptural traditions Sardis may have known in the time prior to the late seventh century B.C. is as yet an open question, but some sparse rays of light are cast upon this dark phase by two pre-Lydian works, with which we begin our account.

The Prehistoric Prelude

The earliest piece claimed so far for the Sardis region is a powerful small head made of serpentine (Cat. no. 229, Figs. 396, 397, 398, 399) and dating to the late Neolithic phase of Anatolian culture, possibly to the fifth millennium B.C. Its stylistic parallels are with the masterpieces of late Neolithic sculpture of Central and Western Anatolia found at Hacılar, Can Hasan, and Çatal Hüyük.2 Serpentine does not seem to occur at Sardis and thus this remarkable work may have been imported from another area. As long as it remains isolated, we cannot consider it a completely safe witness for the existence of a Neolithic school of sculpture at Sardis.

That the early Bronze Age peoples, who lived in the Sardian plain in the third millennium B.C., practiced sculpture on a small scale is confirmed by a silver figurine of a ram found in a grave3 in the cemetery of Eski Balıkhane on the Gygean Lake (Fig. 2, map). The same cemetery yielded a fragmentary stone figurine, perhaps the image of a goddess (Cat. no. 1, Figs. 6, 7). Future finds may yet link these early essays in plastic arts to the continuous tradition of stone sculpture that began in the time of the Lydian kingdom.

-

Şek. 396

Small head of a woman (?), Private Collection. ()

-

Şek. 397

Small head of a woman (?), Private Collection, right profile. ()

-

Şek. 398

Small head of a woman (?), Private Collection, back. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 399

Small head of a woman (?), Private Collection, left profile. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 2

Sardis and surrounding region. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 6

Lower body and feet of prehistoric idol. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 7

Lower body and feet of prehistoric idol. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

The Lydian Era (680-547 B.C.)

The era of the Lydian kings was the time of Lydian power and affluence. Pioneering Greek artists like Glaukos of Chios (infra, Ch. III, “Literary and Epigraphic Evidence,” no. 3) made a silver bowl and iron stand decorated with animals and flowers for King Alyattes (610?-561), and Theodoros of Samos made a silver bowl for Croesus (560-547), who in turn gave a golden kore (“baker woman”) and lion to Delphi and dedicated golden bulls and marble reliefs for columns at Ephesus (Ch. III, “Literary and Epigraphic Evidence,” nos. 5-9).

Imports attest relations with Egypt by seals from Naucratis,4 with Assyria and Babylon by a few seals and bits of glazed pottery. These slight archaeological data back up the substantial literary and epigraphic tradition which reveals the presence of Lydians at the court of Babylon around 600 B.C.5 A well known ivory head found in a tomb at Sardis is either Phoenician or under immediate Phoenician influence.6 A rock crystal lion is clearly of a “Late Hittite” type.7 There are Kimmerian and Scythian chapes and bronze horse trappings8 and a series of bronze animals probably inspired by either Scythian or Iranian prototypes.9 The most important aspects of coinage, such as the guarantee by the king, and probably the use of the lion as a royal symbol, as well as the formal traits of the earliest Lydian lions on coins, point to Assyria and Babylon.10

From such a great range of political, commercial, and artistic contacts, one might have expected that a special and distinct epoch of Orientalizing influence at Sardis would precede the dominance of Greek models. Yet unlike Phrygia, which in the later eighth and seventh century B.C. had an artistic phase that was directly influenced by the “Late Hittite” principalities Urartu and Assyria — an influence reflected in sculpture and distinguished by magnificent imports11 — Lydia, as far as stone sculpture is concerned, presents itself from the beginning as a region of archaic Eastern Greek art.

The best Lydian sculptural work was probably done in the precious materials, gold and silver, and, given the Lydian interest in metallurgy, possibly in bronze as well. The few examples of small-scale gold sculpture preserved, the tiny earring with a ram of ca. 600 B.C. and the four little lions in Istanbul and Oxford, seem to be of high quality.12 The little bronzes of hawks, ibexes, and boars represent types of which we have almost no counterparts in stone. Sculpture in pottery technique such as a wild bearded man and a Persianizing(?) Lydian13 was experimental and colorful, and the mould-made architectural terracottas which adorned the buildings constituted a comprehensive vehicle for narrative and decorative functions.14

If we consider the half century after the Persian capture of Sardis, in ca. 547 B.C., as still “Lydian” in terms of art and culture, the number of pieces assignable to the Lydian era is between thirty and forty. Unlike the great sanctuaries of Eastern Greece, the Heraion of Samos and the temple of Apollo at Didyma,15 Sardis has yielded no treasure trove of archaic sculpture in one area, either sacred or public. Finds made by the first Sardis expedition in the precinct of Artemis and dated largely to the Hellenistic and Roman eras were not abundant. With only one set of lions (Cat. nos. 27, 28, 29, Figs. 105-117) and one stele (Cat. no. 47, Figs. 153, 154) found in their original positions, and only one piece found in a probably original stratified context (Cat. no. 16, Figs. 68, 69) Sardian sculpture contributes few chronological check points.

Iconographically, the material of the Lydian era is spotty and uneven. Nonetheless, some distinctive features emerge. The prominence of lions, which constitute approximately one third of all the sculpture of the Lydian and Persian eras, and a relatively consistent representation of sepulchral and votive stelai afford enough material to treat these groups as continuous developments within these periods (see “On Lions,” “On Stelai” infra).

Draped female figures, shown as goddesses or as votaries, far outrank male figures—with some eight representations of very diversified types (Cat. nos. 3-11, Figs. 9-62). It is striking that at least three of these are representations which enframe frontal figures in temple-like settings (Cat. nos. 6, 7, 9, Figs. 16-19, 20-50, 58-60).

One Lydian claim to iconographic invention must be revoked. In 1905, L. Curtius proposed a double-herm statue of kouros type from Sardis in Berlin as the ancestor of the archaic Greek herms (Cat. no. 249, Figs. 431, 432). He dated it around the mid-sixth century B.C. and thus earlier than the earliest stone herms known in Greek sculpture. The piece has since been convincingly identified as part of a Roman fence of herms,16 but it may reproduce an archaic original. In any case, one can discern a Lydian taste for a mixture of relief and plastic figures in the small priestesses(?) with back pillars (Cat. nos. 4, 5, Figs. 11, 12, 13, 14, 15).

As to the use of relief proper in friezes of metopal panels, our idea of Lydian capabilities would be very slight were it not for the astonishing display of eighteen reliefs on the Cybele shrine (Cat. no. 7, Figs. 20-50). They represent a procession of priestesses to the image of Cybele, heraldic lions, dancing komasts and maenads, and six mythological scenes, of which Herakles and the Nemaean lion, Peleus in the tree, and Pelops on a chariot may be identified. These seem to have been painted panels in shallow relief, rising three stories high, perhaps in imitation of Babylonian wall-high decoration.17 Thus, the miserable state of survival of Sardian sculpture may lead to treacherous mistakes: only the discovery of this temple model makes the Lydians known as experimenters and leaders in the formulation of Greek architectural sculpture.

Turning to the historical development of style, we must first ask whether or not there was an Orientalizing phase that drew on Near Eastern and “Late Hittite” rather than Eastern Greek prototypes. Among the Sardian sculpture there are four borderline cases, all of them dating between ca. 620 and 575 B.C. The monotonous frieze of deer (Cat. no. 230 Fig. 400) is clearly not Greek in its repetitiousness. R. D. Barnett cited it as one of the proofs for the existence of a Lydian school of ivory sculptors,18 presumably in direct dependence on Phoenician ivorists such as were active at Ephesus. The same school may have produced the ivory head found at Sardis.19 Ephesian ivories again and “Late Hittite” reliefs can provide parallels for the “laughing lion” from the Synagogue (Cat. no. 26, Figs. 102, 103, 104), but one might also compare him to the “kissing lions” of a Lydian vase painting — both are distinguished by the same kind of folkloric charm and bonhomie. Such vase paintings are dated to the first quarter of the sixth century B.C. by C. H. Greenewalt, jr.,20 who has been able to distinguish an Orientalizing Sardis style within the general Greek style having Wild Goat decoration.

Matters are somewhat clearer with the Anatolian image of a goddess (Kore?) known through a copy on a Roman column capital (Cat. no. 194, Fig. 344) and the little head with a crown (polos), again of a goddess — perhaps with a monster bird on the crown (Cat. no. 3, Figs. 9, 10). In both cases, the attire is clearly Anatolian, but the general style and concept of a small divine image is much the same as that of the beautiful seventh century wooden Hera of Samos.21

Since some works of metal sculpture (gold ram, silver and bronze hawks, bronze ibex)22 do not depend on Greek models, we must keep an open mind toward the possibility of direct stimuli from the Near East. However, at the moment it appears that between ca. 650 and 575 B.C., there was a phase of Lydian stone sculpture which was Orientalizing in style yet essentially dependent on Eastern Greek mediation of Near Eastern models, rather than on direct contacts with the Near East.

Ephesian ivories and Samian marble statues have provided the models for the strange little marble priestesses and the snake goddess datable from ca. 580 to 530 B.C. (Cat. nos. 4, 5, 6, Figs. 11-19). Henceforth the Eastern Greek schools of sculpture constitute the framework within which Lydian sculpture moves. There is, however, a striking difference between the majestic over-lifesize women by the "Cheramyes Master" of Samos23 and the Lydian naiskos statuettes measuring one third of lifesize or less. The naiskos reliefs themselves pose a problem: while such enframing shrines with frontal images are known especially in connection with Cybele at Kyme and in Miletus, earlier examples may have occurred in Phrygia — a reminder that artistic forms and religious iconography need not always come from the same direction.24

We are still uncertain about the identification and the iconography of early Lydian divinities — a moon goddess(?), a snake goddess, a lion goddess, a hawk divinity, a goddess(?) with necklace are represented in stone and metal. They may be Kore, Cybele (both together with snakes and lions on Cat. no. 7, Figs. 20-50), and the Lydian equivalent of Aphrodite (Cat. no. 9, Figs. 58, 59, 60). No male Lydian Zeus (Levs) or any other god has been identified in Lydian stone sculpture. One wonders whether he might be represented by the strange bearded head forming the upper part of a clay jug.25 Though scholars repeatedly identify with Artemis the potnia theron shown on Sardian terracottas and stamp seals,26 in the only certain representation of Artemis at Sardis she appears with a stag (Cat. no. 20, Figs. 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83). It is Cybele who owns the lions not only on the votive reliefs (Cat. nos. 20, 21, 26 Figs. 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 102, 103, 104) but above all on her altar (Cat. nos. 27, 28, 29, Figs. 105-117) in the gold refinery area on the Pactolus. According to Sophocles, too, it was the Mountain Mother, Cybele, seated on lions, who ruled over the gold rich Pactolus.27 The only argument for a connection of Artemis and lions at Sardis is the monument of Nannas (Cat. nos. 235, 236, Figs. 405, 406, 407, 408, 409) and it does not really prove anything for the Lydian period.

The same uncertainty — sacred to Artemis or sacred to Cybele — arises with respect to a bird of prey. Its stone statue, identified as an eagle, formed part of the unreliable Nannas monument in the Artemis Precinct (Cat. no. 238, Figs. 413, 414, 415). A similar bird of silver was found in an archaic grave and described as a hawk, and according to Lydian inscriptions, graves were protected by Artemis. An example in bronze, however, was found near the altar of Kuvava (Cybele).28

To return to style, the one clear influence from mainland Greece in the first half of the sixth century B.C. is that of Corinth. One may discern it in the goddess with a polos (Cat. no. 3 Figs. 9, 10). It is also prominent in the Main Avenue lions (Cat. nos. 31, 32, 33, Figs. 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, ca. 560 to 550 B.C.) and in the reliefs of the Cybele shrine executed ca. 530 B.C. (but the buildings and the reliefs shown might be earlier, Cat. no. 7, Figs. 20-50). This artistic link to Corinth jibes well with the stories of friendship between King Alyattes and the tyrant Periander of Corinth. And it was the treasury of the Corinthians at Delphi where the presents of the Lydian kings were kept.29

In this assessment of Greek regions which influenced Sardian sculpture we may be underestimating the Aeolid. There seem to be various connections in vase painting and terracotta reliefs between Sardis and the cities north of Smyrna. The peculiar "sea lion" head used on the lions of the Kuvava altar (ca. 570-560 B.C., Cat. nos. 27, 28, 29, Figs. 105-117) seems to be imitated from phokai, the seals of Phokaia;30 and the earliest and most beautiful of Lydian stelai may have been fashioned after stelai from the Aeolid rather than Samos (Cat. no. 45, Figs. 148, 149).

The kouros, or nude male youth, focal subject of Greek sculpture on the mainland and represented by important examples at the Eastern Greek sanctuaries of Samos and Didyma,31 is only doubtfully attested at Sardis and perhaps only in the fifth century. A bit of hair (Cat. no. 14, Fig. 66) may be archaic, 540 to 520 B.C., but the stele Cat. no. 232 (Fig. 402) and the fragment Cat. no. 15 (Fig. 67) probably date after 500 B.C. The only archaic draped torso in the round (Cat. no. 8, Figs. 51, 52, 53, 54) is controversial; it may be a maiden or a standing male mantle figure, much favored in the Eastern Greek sculptural repertory (see Figs. 55, 56, 57).

The closest parallel to the seated male figure on the late archaic stele of Atrastas (Cat. no. 17, Figs. 70, 71) comes from Rhodes, which was artistically in the Eastern Greek ambient. A file of horsemen on squat horses (Cat. no. 231, Fig. 401), very different from the elongated relief horsemen on a Lydian vase of the seventh century,32 may belong to the Persian rather than to the Lydian era.

As to monsters and animals other than lions, we may have an archaic female siren (Cat. no. 40, Figs. 139, 140, 141) and an archaic headless recumbent sphinx (Cat. no. 41, Figs. 142, 143). A bird of prey holding a hare or rabbit may be a hawk or an eagle (Cat. no. 238, Figs. 413, 414, 415). An archaic frog (Cat. no. 43, Fig. 146) may come from a fountain.

The earliest sphinx sejant is apparently of the fifth century (Cat. no. 239, Figs. 416, 417, 418). It is a double-sided animal, as is natural for the support of a throne; such double-sided creatures occur also among early archaic lions (Cat. no. 23, Figs. 87, 88, 89). This double-sidedness is not always easily explained. It m a y be a Lydian predilection, for it occurs not only on the enigmatic black-lava fragment of a winged monster (?) Cat. no. 16 (Figs. 68, 69) but also on a large double-sided relief of a lion (unpublished) found at Hypaepa.33

Croesus gave figured columns to the temple of Artemis at Ephesus and he confirmed their dedications with inscriptions in Lydian and Greek. Something of this bilingual quality seems to have entered into the school of sculpture which formed at the huge project, a school that one might call Lydo-Ephesian. It seems to be distinguished by a certain heavy fleshiness of form and luxury of costume.34 Apart from the recumbent Nannas lion (Cat. no. 236, Figs. 407, 408, 409), its style is best illustrated by the mantle torso in Manisa (Cat. no. 8 Figs. 51, 52, 53, 54). Having begun in the 550s, the style and the school did not go out of existence with the downfall of Croesus in 547 B.C. but continued as the huge task of decorating the giant temple progressed — with the recognizable Croesan phase lasting perhaps until 525 B.C.35 At least the image of the Cybele shrine (Cat. no. 7, Figs. 20-50) maybe counted as a document of that late Croesan phase.

What then was Lydian sculpture? Perhaps we have not as yet enough material to characterize it, and its very closeness to the Eastern Greek schools makes it difficult to discern sustained Lydian traits. We can see, however, that some Lydian pieces tend to be more linear than the Greek models, others seem softer and more massive. Among the stone sculpture preserved, we do not find an evocation of Lydian luxury as vivid and detailed as in the painted terracottas.36 Some un-Greek traits may be detected in the attire of the little priestesses and of the Manisa "kore" (Cat. nos. 4, 5, 8, Figs. 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 51, 52, 53, 54). These maidens add to the repertoire of Sardian stone sculpture an Anatolian flavor that distinguishes it from the creations of the Samians or Milesians. Sardian stone sculpture cannot be considered merely a provincial offshoot of the Eastern Greek, characterized only negatively by a lack of skill.37

In contrast to the rustic linearism and caricaturel-ike misunderstandings of Greek models one finds in Phrygian sculpture farther inland, Sardian work through the sixth century B.C. is of the same general technical competence as Greek. From the Cybele shrine (Cat. no. 7, Figs. 20-50) and other fragments we surmise that the leading Lydian sculptors, the colleagues of Glaukos and Theodoros, were among the pioneers in formulating both the Ionic order and Ionic sculptural types — possibly lions, mantle figures, and stelai. They were thus among the leading artists of their time. In a remarkable social cleavage, this "high class" Lydian art is quite distinct from a lower level of sculpture that has a kind of naive and expressive folkloric charm, especially in the representations of animals, a charm that is also encountered in Lydian vase painting. However, even on this folk level Lydian sculpture never becomes wholly un-Greek and barbarous.

-

Şek. 105

Restored altar at PN with casts of lions 27 (S67.016), 28 (S67.032), and 29 (S67.033) in place, looking S. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 117

Recumbent lion on plinth, SW corner of altar, in situ. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 153

Chamber tomb stele, now lost. Plan and elevation of chamber tomb showing placement of stelai (From Sardis I (1922) ill. 178) ()

-

Şek. 154

Chamber tomb stele, now lost. ()

-

Şek. 68

Two-sided relief fragment with folds or feathers. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 69

Two-sided relief fragment with folds or feathers. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 9

Small crowned female head, front. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 62

Upper part of under-lifesize female torso. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 16

Fragment of a goddess holding a snake (?) standing in columnar shrine, "South kore." (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 19

Fragment of a goddess holding a snake (?) standing in columnar shrine, "South kore," column fragment. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 20

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine" (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 50

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine," Panel R. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 58

Relief of frontal standing draped female figure. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 60

Relief of frontal standing draped female figure, drawing. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 431

Double-sided herm with kouros figure on one side and herm on the other, Berlin Staatliche Museen 883. ()

-

Şek. 432

Double-sided herm with kouros figure on one side and herm on the other, Berlin Staatliche Museen 883, drawing from Berlin Beschreibung, 354, no. 883. ()

-

Şek. 11

Lower part of Archaic kore, "North kore" (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 12

Lower part of Archaic kore, "North kore," side view. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 13

Lower part of small Archaic kore. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 14

Lower part of small Archaic kore, side view. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 15

Lower part of small Archaic kore, back view. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 400

Frieze with grazing deer, British Museum, B 270. (British Museum’unn şahsi fotoğrafı.)

-

Şek. 102

Lion couchant, left side. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 103

Lion couchant, right side. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 104

Lion couchant, detail. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 344

Anatolian goddess. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 10

Small, crowned female head, profile view. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 59

Relief of frontal standing draped female figure, detail. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 78

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 79

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers, reconstruction drawing of naiskos. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 80

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers, 3/4 view. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 81

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers, detail of Artemis. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 82

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers, detail of Cybele. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 83

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers, detail of two worshippers. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 84

Relief of Cybele seated with lion in her lap and at her feet. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 85

Relief of Cybele seated with lion in her lap and at her feet, 3/4 view. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 405

Lion sejant from Nannas monument, Metropolitan Museum of Art 26.59.9, left profile. (Metropolitan Museum of Art’ın şahsi fotoğrafı; The American Society for the Excavation of Sardis hediyesi, 1926.)

-

Şek. 406

Lion sejant from Nannas monument, Metropolitan Museum of Art 26.59.9, back. (Metropolitan Museum of Art’ın şahsi fotoğrafı; The American Society for the Excavation of Sardis hediyesi, 1926.)

-

Şek. 407

Recumbent lion from Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4028, shown as excavated by the first Sardis expedtion, front. (Howard Crosby Butler Arşiv, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 408

Recumbent lion from Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4028, shown as excavated by the first Sardis expedtion, back. (Howard Crosby Butler Arşiv, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 409

Lion sejant and recumbent lion from Nannas monument, in situ. (Howard Crosby Butler Arşiv, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 413

Bird of prey (eagle?) holding a hare, from the Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4032. ()

-

Şek. 414

Bird of prey (eagle?) holding a hare, from the Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4032, three-quarter view. ()

-

Şek. 415

Bird of prey (eagle?) holding a hare, from the Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4032, back. ()

-

Şek. 119

Large recumbent lion, left side. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 120

Large recumbent lion, right side. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 121

Large recumbent lion, front. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 122

Large recumbent lion, detail. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 123

Fragment of colossal lion's foot. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 124

Lion's right foot on plinth. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 148

Anthemion (finial). (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 149

Anthemion (finial), back. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 66

Fragment of Archaic kouros head. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 402

Relief with head of bearded man, Metropolitan Museum of Art 26.199.278 (Metropolitan Museum of Art’ın şahsi fotoğrafı; The American Society for the Excavation of Sardis hediyesi, 1926.)

-

Şek. 67

Back of male head. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 51

"Mantle-Wearer," kore (?) Manisa 325, front. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 52

"Mantle-Wearer," kore (?) Manisa 325, right side. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 53

"Mantle-Wearer," kore (?) Manisa 325, back. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 54

"Mantle-Wearer," kore (?) Manisa 325, left side. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 55

Draped youth from Myus, Berlin, Staatliche Museen, SK 1664, front. (Arachne’dan fotoğrafı (http://arachne.dainst.org))

-

Şek. 56

Draped youth from Myus, Berlin, Staatliche Museen, SK 1664, right side. (Arachne’dan fotoğrafı (http://arachne.dainst.org))

-

Şek. 57

Draped youth from Myus, Berlin, Staatliche Museen, SK 1664, back. (Arachne’dan fotoğrafı (http://arachne.dainst.org))

-

Şek. 70

Inscribed stele with seated man (Atrastas, son of Sakardas), Manisa 1. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 71

Inscribed stele with seated man (Atrastas, son of Sakardas), Manisa 1, detail. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 401

Frieze of horsemen, British Museum B 269. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 139

Lower part of archaic siren, front. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 140

Lower part of archaic siren, back. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 141

Lower part of archaic siren, side. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 142

Headless recumbent sphinx, Manisa 311, right side. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 143

Headless recumbent sphinx, Manisa 311, left side. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 146

Relief fragment of frog and support. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 416

Sphinx, presumably part of a throne or seat, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4031, left profile. ()

-

Şek. 417

Sphinx, presumably part of a throne or seat, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4031, right profile. ()

-

Şek. 418

Sphinx, presumably part of a throne or seat, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4031, front. ()

-

Şek. 87

Double-sided relief with archaic lion sejant, side view. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 88

Double-sided relief with archaic lion sejant, side view. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 89

Double-sided relief with archaic lion sejant, top view. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

The Persian Era (546-334 B.C.)

We have no sculptured monuments that can be linked to either the capture of Sardis in 547 B.C. by the Persians or the burning of Sardis in 499 B.C. by the Ionians and Athenians. Even though the Persians overthrew Croesus in 547 B.C. and both Cyrus and Darius took Lydian masons and probably sculptors as well to Iran to build their palaces,38 there is no indication that Persian influence became strong immediately.39 Perhaps it did not become effective until the late sixth century.

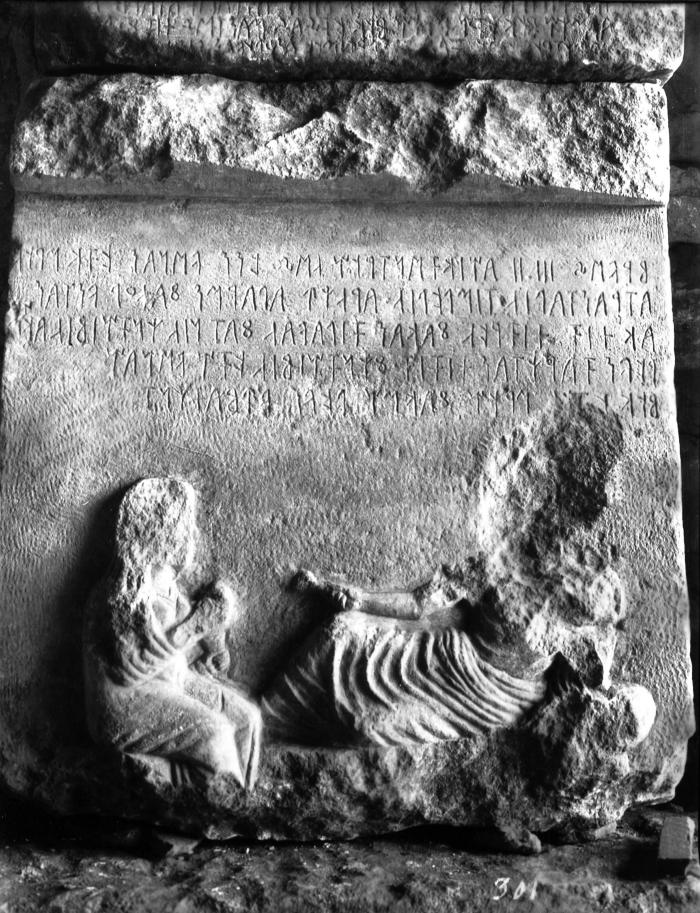

Eventually, as Sardis became virtually the capital of the western part of the Persian Empire, the satrapal court of Sardis emerged as a center for the production of seals and jewelry in Iranian Achaemenid court style.40 They were made not only for satraps and their families but for the many people who took part in the administration of the empire: people with Iranian names like Mitrastas and Atranes but who wrote Lydian not only in their official documents but also on their seals;41 people with Lydian names like Manes, son of Kumlis (Cat. no. 241, Fig. 420) who used both Aramaic and Lydian in their inscriptions and dated them by the regnal years of the Persian kings;42 and people with Lydian names like Bakivas, Sivams, and Manes who used seals with purely official Persian iconography.43 Finally there were those with Lydian names like Nannas who wrote Lydian and Greek (Cat. no. 274, Fig. 465).

In glyptic art, it is possible to discern the large groupings of essentially Iranian-inspired and essentially Greek-inspired art.44 The situation is much less clear in sculpture, where, to be sure, only some twenty pieces can be assigned to the Persian period. Was there a satrapal school of sculpture at Sardis? The resemblance of the anthemion stele Cat. no. 46 (Figs. 150, 151) to the Daskylion stele (Fig. 152) and of stele Cat. no. 45 (Figs. 148, 149) to Persian ornament suggests that there were connections with the satrapal residence at Daskylion — and figurative scenes, Persian in their iconography, may have been known at Sardis as they were at Daskylion. In subject matter and customs the little pediment from a mausoleum-temple of a high official family (Cat. no. 18 Figs. 72, 73, 74) may be accounted a satrapal document.45 To this Persian-influenced aspect may also belong the horsemen file from Bin Tepe (Cat. no. 231, Fig. 401). A tantalizing fragment of a figure in Oriental attire (Cat. no. 13, Fig. 65) hints that large-scale architectural sculpture did exist.

Epigraphic and literary sources indicate that images of Zeus Baradates (Ahura Mazda) and Artemis Anahita were worshipped at Sardis, but no representations in sculpture have been found that may be identified with certainty; nor have we found any representations of fire priests.46 A stele in Izmir (Cat. no. 233, Fig. 403, ca. 450-425 B.C.) showing a woman is also the only stone relief that seems to reflect direct influence from Persian palace reliefs in the rendering of drapery with the peculiar central fold. The same rendering appears on seals attributed to Sardis.47

All of these monuments show some traits responding to Persian taste, but none of the stone monuments is done in Persian court style as clearly as are the Sardian seals, nor have we found in stone sculpture of this period such Persian themes as bearded sphinxes or lion griffins. The overall style of stone sculpture is closer to Greek.

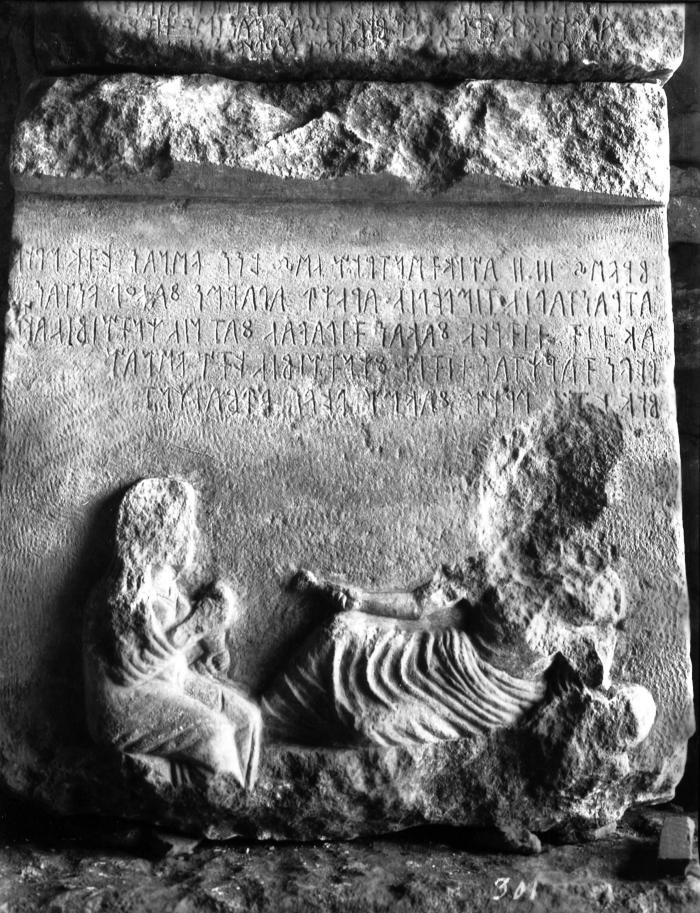

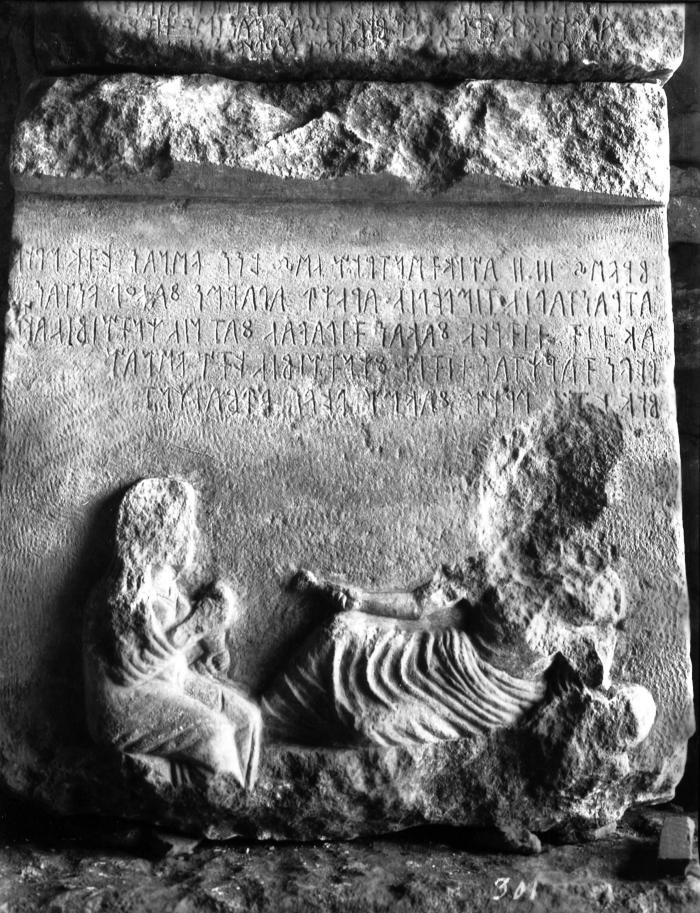

The subject of m a n and wife at a funerary meal, beloved by the Persians, reappears toward the very end of the period on the stele of Atrastas, son of Timles (Cat. no. 234, Fig. 404), dated in the fifth year of the rule of Alexander the Great (330-329 B.C.). It shows the sculptor slipping into a linear, possibly late Achaemenid/Anatolian folkloric style.48

To turn now to the sources of the predominant Greek influences, the sculpture of the later sixth century permits a choice between Eastern Greek or Athenian influence, notably in the portrayals of the korai type with the large central fold (Cat. nos. 7, 9, Figs. 33, 34, 39, 58, 59, 60). Historically, it is not implausible to think of Athens as a source. Alcmaeon, head of the art loving Alcmaeonid family, who rebuilt the temple of Apollo in Delphi after 546 B.C., had visited Croesus,49 and the sons of Peisistratos maintained close relations with the Persian satraps at Sardis. Quite a number of Attic black-figure vases were imported into Sardis between 560 and 480 B.C. And Attic works of art were brought to Sardis as booty in 480 B.C.: for example, the bronze statue of a water carrier originally dedicated by Themistocles in Athens (see Ch. III, “Literary and Epigraphic Evidence”, no. 11). To the Attic tradition, too, may belong a fragment of an early classical male head (Cat. no. 15, Fig. 67).

For the period between ca. 500 and 430 B.C. we may discern two major stylistic sources. One is the non-Attic style of the Greek islands, which encompassed not only the Cyclades but also Rhodes and Knidos. It is difficult to draw a clear line between these Cycladic-Boeotian stelai and the "soft style" of the Eastern Greek, Ionian school whose influence certainly extended into northern Greece (Thasos, Dikaia) as well as into southern Asia Minor (Lycia).50 At Sardis, the influence of the soft style is attested for ca. 500 B.C. by an animal frieze fragment (Cat. no. 22, Fig. 86) and a stele fragment with male head (Cat. no. 232, Fig. 402). Even though it is not from Sardis, the early classical "Borgia stele" of ca. 470-460 B.C. (Cat. no. 269) is a good illustration of immediate Eastern Greek affiliations. Then comes the satrapal pediment (Cat. no. 18, Figs. 72, 73, 74) of ca. 430 B.C. Its obvious relation is to the great masterpiece of Eastern Greek soft style in the service of Persian officialdom, the so-called Satrap Sarcophagus from Sidon.51 Artists working in this Greek soft style but with Persian iconography may have produced the highest level of sculpture among the satrapal courts also at Sardis.52

The two pieces dependent on inspiration from the Cycladic-Thessalian-Boeotian circle are the votive stele Cat. no. 19 (Figs. 75, 76, 77) and the Persianizing sepulchral stele Cat. no. 233 (Fig. 403) which in overall design is so strangely close to the stele of Polyxenaia from Larissa in Thessaly53 (see infra, “On Stelai”). Both stelai date from ca. 450-425 B.C. One might have expected that the bitter fighting in western Asia Minor during the later years of the Peloponnesian War and prior to the King's Peace (386 B.C.) adversely affected Greek influences in art, but this does not seem to be the case. The bilingual Aramaic-Lydian stele of Manes, son of Kumlis, presumably a Persian official, dated 394 B.C. by regnal years of Artaxerxes, follows closely in the design of its anthemion the Attic decorative vocabulary of the late classical phase (Cat. no. 241, Fig. 420). Attic influence is also paramount among other stelai, votive and sepulchral (see infra, “On Stelai,” Cat. nos. 20, 21, 240, 242, Figs. 78-85, 419, 421).

The later, more naturalistic lions from Sardis (Cat. nos. 25, 38, 39, Figs. 92-101, 135-138) also seem to depend on Attic models.54 One example demonstrates the possible influence of the great Mausoleum style55 created chiefly under the impulse of Skopas in Asia Minor (ca. 360-350 B.C.; cf. Cat. no. 38, Figs. 135, 136).

The scattered marble fragments offer little encouragement for iconographic research. The most interesting problem concerns the typology of Cybele. One type of Cybele can be reconstructed as showing the goddess possibly standing and flanked by two pairs of seated lions (Cat. no. 25, Figs. 92-101). A second type of standing Cybele, holding a lion to her breast with one arm, and a standing Artemis holding a stag are reflected on a stele (Cat. no. 20, Figs. 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83), both apparently fashioned after statues of the mid-fifth century. Finally, the votive relief Cat. no. 21 (Figs. 84, 85) exhibits a third type, a variation on the famous seated Cybele image made by Agorakritos in the late fifth century. It was perhaps this last image that Sophocles hymned as seated on lions, and Timotheos envisioned as wearing a chiton with black leaves.56 The three types may represent three successive images of the goddess in her famous Metroon burned by the Greeks in 499 B.C. but apparently reconstructed before 465.57

Finally, during the later part of the Persian era (ca. 450-330 B.C.) in the admittedly spotty array of sculptured work found at Sardis, we may perceive a decline in artistic quality to the level of reasonable but somewhat provincial competence, with Eastern Greece, the Cyclades, and subsequently Athens providing the principal models.

-

Şek. 420

Anthemion with Lydian-Aramaic bilingual, stele of Manes, son of Kumlis, Izmir Archaeological Museum 691. (Howard Crosby Butler Arşiv, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 465

Bilingual dedication of Nannas Bakivalis to Artemis. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 150

Fragment of anthemion. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 151

Fragment of anthemion, detail. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 152

Stele from Daskylion, Istanbul Archaeological Museum (Arachne’dan fotoğrafı (http://arachne.dainst.org))

-

Şek. 148

Anthemion (finial). (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 149

Anthemion (finial), back. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 72

Part of a pediment. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 73

Part of a pediment, detail of ornament. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 74

Part of a pediment, projection drawing of pediment block. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 401

Frieze of horsemen, British Museum B 269. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 65

Shoulder of colossal draped figure. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 403

Stele with praying woman, Izmir Archaeological Museum 690 (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 404

Funerary stele of Atrastas, son of Timles, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4030 (Howard Crosby Butler Arşiv, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 33

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine," Panel A. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 34

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine," Panel B. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 39

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine," Panel H. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 58

Relief of frontal standing draped female figure. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 59

Relief of frontal standing draped female figure, detail. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 60

Relief of frontal standing draped female figure, drawing. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 67

Back of male head. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 86

Fragment of Archaic relief with part of running animal. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 402

Relief with head of bearded man, Metropolitan Museum of Art 26.199.278 (Metropolitan Museum of Art’ın şahsi fotoğrafı; The American Society for the Excavation of Sardis hediyesi, 1926.)

-

Şek. 75

Stele with veiled frontal female. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 76

Stele with veiled frontal female, L. side. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 77

Stele with veiled frontal female, detail. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 78

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 85

Relief of Cybele seated with lion in her lap and at her feet, 3/4 view. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 419

Part of sepulchral stele with palmette anthemion, Izmir Archaeological Museum 695. (top fragment only) (Howard Crosby Butler Arşiv, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 421

Funerary stele with Lydian inscription and rounded palmette anthemion, stele of Alikres, son of Karos, Izmir Archaeological Museum 694. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 92

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lions A and B. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 101

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lion A from above. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 135

Walking lion, Manisa 306, right side. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 138

Part of frame with walking lion. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 136

Walking lion, Manisa 306, left side. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 79

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers, reconstruction drawing of naiskos. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 80

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers, 3/4 view. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 81

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers, detail of Artemis. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 82

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers, detail of Cybele. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 83

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers, detail of two worshippers. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 84

Relief of Cybele seated with lion in her lap and at her feet. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

On Lions

The Lydians suffered from a regular leontomania. Out of the small lot of sculpture published here twenty-one are lions. The great goddess Cybele (or whatever native goddess preceded her) has lions as her attributes as early as the famous fourteenth or thirteenth century B.C. relief near Manisa.58 The story of Meles (Herodotus 1.84) seems to indicate that under the Heraklid dynasty the lion was a protecting symbol of the royal house. It is doubtful that the stories about Herakles, whose lion skin was taken by Queen Omphale, have any real bearing on this choice of the lion as royal coat of arms as T. L. Shear had suggested.59 Rather the lion was the representative of the great goddess (Cybele) who protected the royal house.

The lion alone appears as a royal symbol on early Lydian coins (late seventh century); from Croesus on, the foreparts of a lion and a bull are used, an abbreviation of a group showing a lion overcoming a bull.60 As proved by the relief Cat. no. 21 (Figs. 84, 85), at Sardis the lion was considered an attribute of Cybele; the association with Artemis is less certain.61 Croesus dedicated a gold lion to Apollo of Delphi (see Ch. III, “Literary and Epigraphic Evidence”, no. 6), and Cahn has argued that lions were also sacred to a Lydian Apollo.62 The appearance of lions on non-royal seals is evidence for a more general protective or symbolic ("courageous like a lion") function.63

As to archaeological evidence for function, the double-sided relief Cat. no. 23 (Figs. 87, 88, 89) was probably part of the throne for an image; the two classical lion pairs Cat. no. 25 (Figs. 92-101) were possibly flanking an image. The classical relief Cat. no. 39 (Figs. 137, 138) is perhaps from a frame for a small image. In all these cases, Cybele is the most likely divinity.

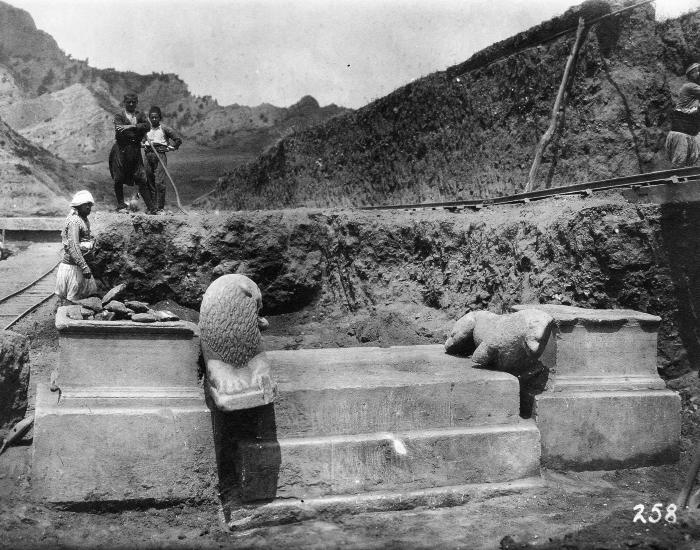

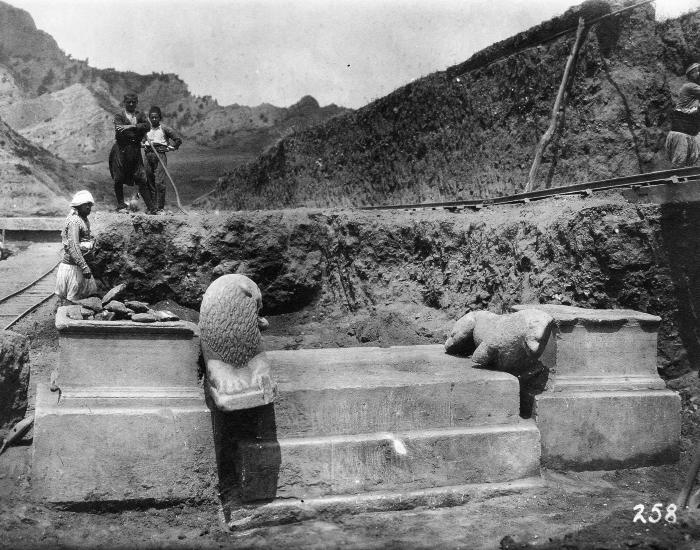

In architectural context, the two and a half lions Cat. nos. 27, 28, 29 (Figs. 105-117) belong to an altar of Cybele (Kuvava) dated by the excavator, Andrew Ramage, ca. 580-570 B.C. and are thus to be considered dedications. The most important lion spout, Cat. no. 237 (Figs. 410, 411, 412) belonged to a sacred structure — the temple or altar of Artemis is among the possibilities. The little archaic lion Cat. no. 36 (Fig. 133) is an acroterion, possibly from an archaic sarcophagus. The majestic lion found in the Main Avenue and its counterpart (Cat. nos. 31, 32, 33, Figs. 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124) might have been guardians of a gate.

It is unfortunate that the Nannas monument (see Cat. nos. 235, 236, 238, 274, Figs. 405-409, 413-415, 465, 466) can be taken as safe evidence only for late Roman taste. Set up in this form in the second or third century A.D., it proves that the late Romans considered lions and the eagle sacred to Artemis. H. von Gall has shown that such a grouping is attested for Cappadocian funerary monuments of the Persian era.64 It is plausible to assume that the Romans collected the two lions and a bird of prey from the votives possibly overthrown by the floods in the Artemis Precinct. Given the fact, however, that the Nannas base was itself reused (and had initially carried a human figure), we cannot be sure that the combination of the seated and the recumbent lions with the eagle was original. There is, however, cause to conjecture that both types were originally presents to Artemis.

In Greece both the seated and the recumbent types of lion appeared on funerary monuments of the archaic and classical periods and the walking lion in those of the classical era.65 Of special interest for Asia Minor is the column with recumbent lion inscribed Mikos Metrodoro in Ankara.66 Thus far we have no evidence that this type of sepulchral lion monument existed at Sardis during the Lydian and Persian periods.

Most scholars seem to agree that Homer's poetry is sufficient proof that lions (probably the smaller Asiatic species) existed in western Asia Minor in early historical times.67 The matter is of some interest both to explain the importance of the lion for the royal house — more plausible if based on firsthand experience or at least memory of the prowess of real lions — and to assess the renderings of lions in Lydian art.

Royal lion hunts were common in Assyria and possibly Babylon and Persia as well in the time when the Lydians had contact with Assur and Babylon, and the lion was used as the royal sign in these two cities.68 In 480 B.C., during the Persian era, many Lydians who served in the army of Xerxes could have seen lions in action when they attacked the king's camel train in the southern Balkans (Thrace, Herodotus 7.125-126). Because lions were imported into Greece in the fourth century B.C.,69 it would not be unthinkable that satraps at Sardis, too, had lions imported for hunting. However, no lion bones were identified among the several thousand animal bones found in the Sardis excavations and examined by S. Doğuer and associates.70

Although some correct observations appear, such as the dewclaw (small fifth toe or thumb on forefoot) in Cat. no. 25 (esp. Fig. 98), the Sardis lions seem to have been usually portrayed without benefit of life study.71 Some "errors" imputed to artists need not be errors. It is certainly an error to show the lioness with a mane as in Cat. no. 34 (Figs. 125, 126, 127, 128, 129), but a young male lion until he is three to four years old (and apparently some even after that age) is maneless.72

Akurgal has suggested that the type of lion portrayed on Lydian coins is a mixture of Assyrian, "Late Hittite," and Greek elements.73 It seems plausible to assume a non-Greek, "Late Hittite" model for the earliest complete lion found at Sardis Cat. no. 26 (Figs. 102, 103, 104, ca. 600-570 B.C.). Thereafter, the likelihood that Greek models were imitated is considerable. Corinthian inspiration seems probable for the large lion Cat. no. 31 (Figs. 119, 120, 121, 122) and certain for the seated lions shown on the Ionic Cybele shrine Cat. no. 7 (Figs. 38, 42, 43).

The Eastern Greek standard recumbent lion type owes perhaps as much to Lydians as to Ionians. It seems to develop from the “Late Hittite” type74 between 600 and 550 B.C. The lioness Cat. no. 34 (Figs. 125, 126, 127, 128, 129) is a delightful early Lydo-Ionian attempt at "scientific" naturalism, around mid-sixth century. The recumbent type was most likely the type of the golden lion of Croesus, as it recurs in golden jewelry of the Croesan era.75

A peculiar feature of the altar lions Cat. nos. 27, 28, 29 (Figs.105-117, ca. 570-560 B.C.) is the small sea lion or seal-like heads. One wonders whether seals (phokai), so popular in Phokaia and Larisa, were taken as models for lion heads either in nature or possibly from terracotta sculpture.76

The great lion found near the Synagogue (Cat. no. 31, Figs.119, 120, 121, 122) and the recumbent lion from the Nannas monument (Cat. no. 236, Figs. 407, 408, 409) turn their heads frontward. Their faces with rolling eyes suggest renewed contact with Assyrian-Babylonian tradition, presumably in the Croesan era. The recumbent type seems to have continued to the end of the sixth century B.C.

The seated lion from the Nannas monument (Cat. no. 235, Figs. 405, 406) and the double lions found in the Synagogue (Cat. no. 25, Figs. 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101) are valuable for a phase in the development of the seated type as yet little understood. Retaining archaic features, yet betraying knowledge of more naturalistic renderings of the classical age, they illustrate the transition toward classical lions during the fifth century B.C. It is not clear whether they are already inspired by, Greek mainland (especially Attic) lion types.77 There is no such doubt about the walking lions Cat. nos. 38, 39 (Figs. 135, 136, 137, 138) which find close parallels in Attic monuments of the late fifth and fourth centuries B.C.

Considering that very typical Achaemenid lion sphinxes have been found in gold jewelry made in Sardis in the fifth century,78 it is noteworthy that the stone sculpture tended to depict Greek, not Persian, lion types. With the decline of the Lydian culture and language, the popularity of lion statuary seems also to have waned in Lydia. At least, we have not found many Hellenistic or Roman examples.

-

Şek. 84

Relief of Cybele seated with lion in her lap and at her feet. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 85

Relief of Cybele seated with lion in her lap and at her feet, 3/4 view. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 87

Double-sided relief with archaic lion sejant, side view. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 88

Double-sided relief with archaic lion sejant, side view. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 89

Double-sided relief with archaic lion sejant, top view. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 92

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lions A and B. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 101

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lion A from above. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 137

Part of frame with walking lion. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 138

Part of frame with walking lion. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 105

Restored altar at PN with casts of lions 27 (S67.016), 28 (S67.032), and 29 (S67.033) in place, looking S. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 117

Recumbent lion on plinth, SW corner of altar, in situ. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 410

Lion spout attached to rectangular member. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 411

Lion spout attached to rectangular member, detail of lion. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 412

Lion spout attached to rectangular member, drawing with elevations, top view, and section. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 133

Acroterion (?), small recumbent lion from corner of archaic sarcophagus lid? (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 119

Large recumbent lion, left side. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 120

Large recumbent lion, right side. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 121

Large recumbent lion, front. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 122

Large recumbent lion, detail. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 123

Fragment of colossal lion's foot. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 124

Lion's right foot on plinth. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 405

Lion sejant from Nannas monument, Metropolitan Museum of Art 26.59.9, left profile. (Metropolitan Museum of Art’ın şahsi fotoğrafı; The American Society for the Excavation of Sardis hediyesi, 1926.)

-

Şek. 409

Lion sejant and recumbent lion from Nannas monument, in situ. (Howard Crosby Butler Arşiv, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 413

Bird of prey (eagle?) holding a hare, from the Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4032. ()

-

Şek. 415

Bird of prey (eagle?) holding a hare, from the Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4032, back. ()

-

Şek. 465

Bilingual dedication of Nannas Bakivalis to Artemis. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 466

Bilingual dedication of Nannas Bakivalis to Artemis, top. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 98

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lions C and D after restoration. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 125

Lioness, Manisa 303, right side. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 126

Lioness, Manisa 303, left side. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 127

Lioness, Manisa 303, front. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 128

Lioness, Manisa 303, back. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 129

Lioness, Manisa 303, detail showing clamp holes. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 102

Lion couchant, left side. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 103

Lion couchant, right side. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 104

Lion couchant, detail. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 38

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine," R. side, drawing. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 42

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine," Panel K. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 43

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine," Panel L. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 407

Recumbent lion from Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4028, shown as excavated by the first Sardis expedtion, front. (Howard Crosby Butler Arşiv, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 408

Recumbent lion from Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4028, shown as excavated by the first Sardis expedtion, back. (Howard Crosby Butler Arşiv, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 406

Lion sejant from Nannas monument, Metropolitan Museum of Art 26.59.9, back. (Metropolitan Museum of Art’ın şahsi fotoğrafı; The American Society for the Excavation of Sardis hediyesi, 1926.)

-

Şek. 93

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lion B. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 94

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lion B. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 95

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lions C and D in situ near Synagogue apse. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 96

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lions D and C. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 97

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lions D and C after restoration. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 99

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lion C. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 100

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lion C, right profile. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 135

Walking lion, Manisa 306, right side. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 136

Walking lion, Manisa 306, left side. (Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

On Stelai

The Iliad tells how the Greeks, the Trojans, and the Lycians poured big mounds over their dead and set upon them signs or pillars, semata or stelai, as an honor to the dead.79 Like the Lycians, the Phrygians and Lydians also poured big earthen mounds over the burials of their kings and princes.80 In Lydia, the stone markers found over the mound burials seem to have been principally of the so-called phallic or bud type, a circular pillar with a global or oval top. So far, we have no certain report of a rectangular, slab-like stele crowning a Lydian mound.81

The most popular kind of sepulchral monument in Greece from Geometric times on, the stele or rectangular slab or pillar, is abundantly represented in Lydia, both in decorated and inscribed examples.82 As far as we know, however, no rude, irregular stelai of a primitive kind have been found at Sardis, as they were at Neandria where a seventh century B.C. date has been suggested.83

On the present evidence, Lydian stelai have been found only in association with rock-cut chamber tombs. We do not know when the first rock-cut chamber tombs of Sardis were made; a study of pottery finds indicates that late seventh century might be the earliest possible date.84 A chamber tomb, which was built of masonry between 600 and 650 B.C., appeared in the mound of King Alyattes, the only royal burial discovered so far.85

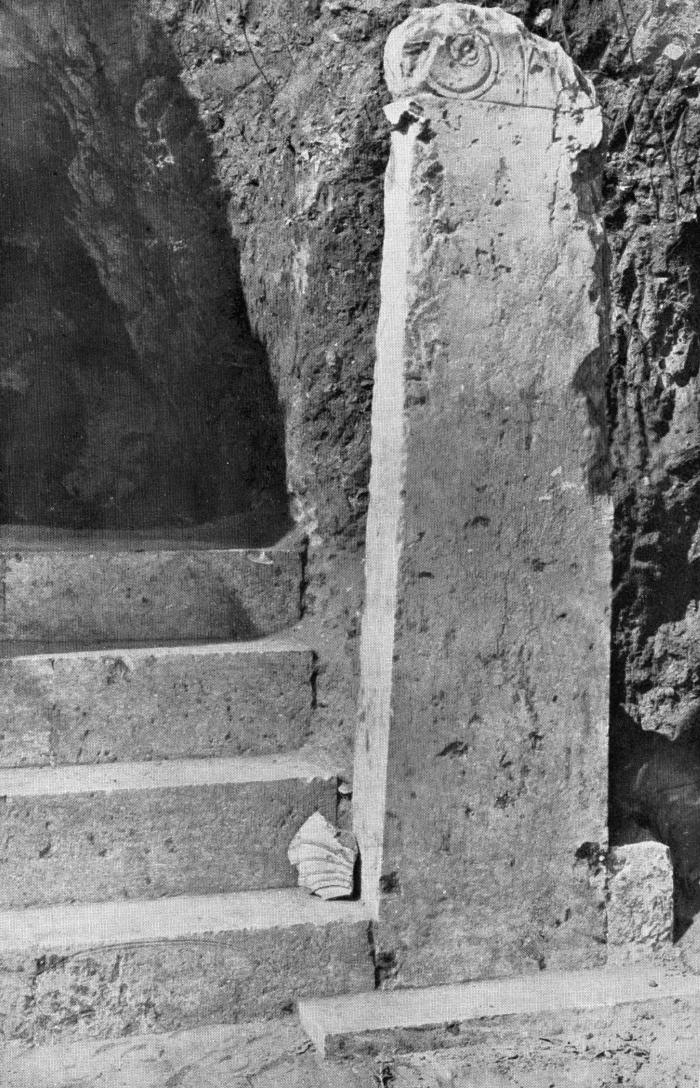

H. C. Butler, who excavated over a thousand Lydian graves, including several hundred chamber tombs, found only two sepulchers with their stelai in place. One of them, Cat. no. 47, presented a most impressive appearance in its original state (Figs. 153, 154). Two mighty limestone pillars, about 10 feet (ca. 3 m.) high, with beautiful floral finials flanked a stair of limestone blocks leading to the facade of the tomb. This arrangement was late archaic, around 500-480 B.C. It may have had parallels and forerunners in Eastern Greece. Thus two flanking stelai, with figures of the deceased, are said to have adorned the tomb facade to which the famous Borgia stele in Naples belongs (Cat. no. 269).86 A symmetrical arrangement of two lions decorated the chamber tomb of a nobleman or ruler at Kazar Tepe,87 at Miletus.

The second stele found by Butler in situ was a small (H. 0.965) inscribed pillar placed at the corner of a chamber tomb "beside and at the end of a long dromos." The date is not before the fifth century B.C., on epigraphic grounds.88

Finally, Butler seems to have observed some instances in which marble stelai were found inside tomb chambers: "these had been preserved but the color designs had disappeared."89

The early example, Cat. no. 47, found in situ had a very wide and shallow base from which the shaft rose (Fig. 154), but later examples probably had the type of base known for votive stelai.90

The real history of the stele at Sardis begins with two decorated anthemia, Cat. nos. 45 and 46 (Figs. 148, 149, 150, 151). By that time the marvelous basic shape of a tall shallow pillar crowned by two Ionic volutes and harmoniously terminated by a palmette had been created, very possibly in Eastern Greece, by combining floral architectural acroteria, based in turn on metal ornament, with the tall monument of stone.91 The question of origins is complicated. On the one hand, majestic, artistically fashioned sepulchral stelai with cavetto floral profile surmounted by a sphinx were used on the Greek mainland since before 600 B.C. On the other hand, the earliest palmette-crowned examples seem to be Eastern Greek, already early archaic.92 According to Buschor the palmette volute stele was invented in Samos around 570 B.C.93 Perhaps we should assume that, as with vase painting, the same artistic problem — that of a majestic stone memorial — was taken up in different ways on the mainland and in Eastern Greece, with the mainland creating and developing the stele with human figures and the Eastern Greek artists favoring the use of Orientalizing floral decorative effects. Masterpieces of floral design appear around the middle of the sixth century in the Aeolid and on the island of Samos.

The Lydian examples depend on these Eastern Greek creations. Thus our earliest preserved finial, the masterly stele from the Pactolus Valley (Cat. no. 45, Figs. 148, 149), is closely patterned on the beautiful Calvert stele from the Troad.94 The Lydian stelai show enough divergencies from the Samian examples to indicate that a local Sardian taste and local typology established themselves soon; perhaps Greek masters did the earliest examples, now lost to us, but I do not believe with Friis-Johansen95 that Ionian sculptors carved such stelai as the late archaic, and possibly retardataire, example Cat. no. 47 (Figs. 153, 154).

The characteristic features of the Sardian stelai may be elucidated by comparing them with the comprehensive Samian series.96 The development at Sardis is continuous and leads from mid-archaic to late classical sculpture.

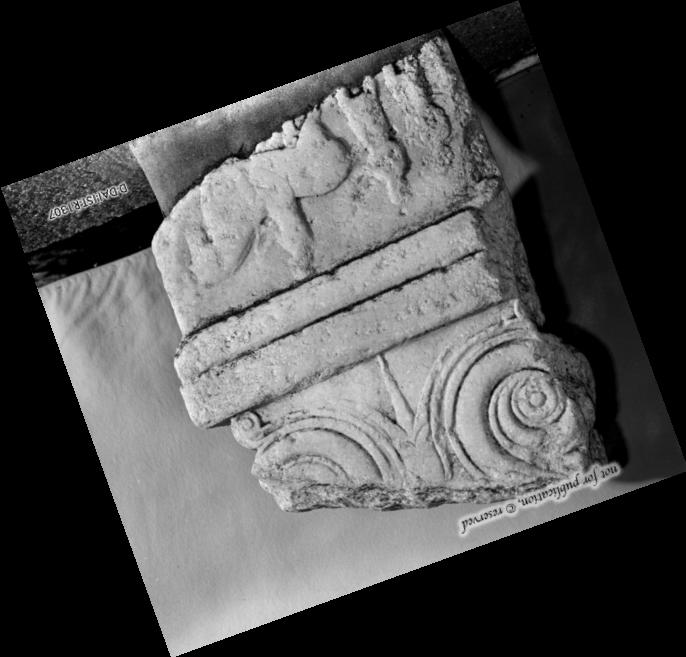

Many Samian stelai express an innate sense of architectural geometry by emphasizing the top palmette as a vertical element and treating the two volutes as a horizontal base with the volutes projecting sideways beyond the palmette in the manner of the volutes of an Ionic capital.97 The earliest Sardian stele gathers all elements of the anthemion into one all-encompassing oval (Cat. no. 45, Figs. 148, 149), and this tendency to treat the finial as a compact unit continues in Lydian stelai of the later fifth and earlier fourth centuries B.C. (Cat. nos. 240, 241, 242, Figs. 419, 420, 421). The effect is softer, heavier than in Samos. Possible exceptions, in which the outside of the stele was carved in various curves that followed the ornament, are the stele from Tomb 813 (Cat. no. 47, Figs. 153, 154) of ca. 500-480 B.C. and Cat. no. 48 (Figs. 155, 156), ca. 450 B.C.; but even in these the volutes do not seem to have projected sideways beyond the stele shaft as in Samos. Nor do we ever find on Sardian stelai the sharp, geometric termination of volutes against the sides, a rather inorganic solution not uncommon on Samos.98

Two features that occurred in Samos briefly are much favored on Sardian stelai: a light convex rise of the "body" of the volute and a rich, rather wide edging (called "pulvinated bands" by H. C. Butler). They are traits of archaic, almost Orientalizing taste for broad decorative effects. And the survival of the broad framing bands and two voluted stems growing antithetically out of the ground gives to the otherwise "modern" stele of 394 B.C. a kind of grandfatherly charm, as a glance at Cat. no. 45 (Figs. 148, 149), the archaic prototype, will show.

When it comes to general types of finial design, Samos does not seem to have the antithetic volute stem composition; in Sardis, in the fifth century, it was developed into a design in which the lower ends of volutes placed diagonally into the corner acquire a leaf-like shape (Cat. no. 49, Fig. 157). This, too, does not seem to have been popular on Samos.99 On the other hand, the so-called lyre capital, which had appeared on Samos ca. 540-530 B.C. and in Athens ca. 530 B.C.100 is known at Sardis only in a fifth century example (Cat. no. 48, Figs. 155, 156).101

Thus, while Sardis stelai carvers clearly represent a Lydian dialect, the beauty of Lydian ornament seems to be due to direct contact with Eastern Greek masters. Unfortunately, neither Miletus102 nor Ephesus, which on historical grounds is the most likely immediate source for Sardis,103 has produced any extensive collections of stelai comparable to Samos. At present, the Samian stelai appear to be closest to those from Sardis. We know that Samian artists worked for Lydian kings: Theodoros made a silver crater for Croesus.104 Therefore, direct influence of Samian designs is entirely possible.

Because marble technique and design of marble monuments go together, we have assumed that the Lydian sculptors depended on the decorative vocabulary of Eastern Greece; yet in gold and jewelry and bronze metal work, the same volutes, palmettes, rosettes, and lotuses were designed and executed by artists working in the Achaemenid Persian court style at Sardis105 in the late sixth and fifth centuries B.C Recently, some stelai have come to light at the satrapal residence of Daskylion which pose the question of a possible existence of a satrapal style in Asia Minor.106 These stelai have anthemia of Greek type, but they also have figurative representations of funerary meals and processions of carts and horsemen.107 The very close resemblance of one of the Daskylion finials (Fig. 152) to one from Sardis (Cat. no. 46, Figs. 151, 152) makes one wonder whether the Sardian stele, too, had similar Persianizing figurative representations. For the moment, we have no proof, but the Persian subject and special style of the pediment Cat. no. 18 (Figs. 72, 73, 74) lend probability to this assumption.

Most of the stelai found at Sardis are datable only by stylistic comparisons. The earliest (Cat. no. 45, Figs. 148, 149) represents the simpler taste of ca. 550-530 B.C. The brilliant, exaggerating, manneristic stage of Eastern Greek ornament is just beginning in Cat. no. 46 (Figs. 150, 151, ca. 530-520 B.C.). For the limestone stele of Tomb 813 (Cat. no. 47, Figs. 153, 154), which displays in its long, thin lotus an advanced, late archaic mannerism,108 we can marshall new chronological evidence: one of the four burials in the chamber tomb contained a well-datable Attic vase of ca. 500-480 B.C.109 The stele may thus be a work of the early fifth century, which shows both survival of mannerist ornament in Lydia into the fifth century B.C. and a linear, conservative touch in the actual execution.

Hitherto, the dating of the material from Sardis suggested a break between the series of archaic stelai reaching into the early fifth century B.C. and the emergence of floral decorative stelai in the late fifth, but I now believe that because of its complicated, two-storied, naturalistic central lotus, the lyre stele (Cat. no. 48, Figs. 155, 156) may descend toward the middle of the century (480-450 B.C.?).110 One can still recognize the same archaic taste for emphatic spirals in the radiant finial of the famous Aramaic-Lydian bilingual (Cat. no. 241, Fig. 420) stele of a Lydian in Persian service who was named Manes, son of Kumlis. It also has, however, advanced features such as the little bell-flowers exactly parallelled on the stele of the Athenians who fell in 394 B.C. in the Corinthian war.111 Its master was clearly under the spell of that wondrous creation, the architectural ornament of the Erechtheion (ca. 420-410 B.C.). Growing out of a wide acanthus chalice and inhabited by birds, the involuted design of the stele of Alikres reflects a later taste, that of naturalistic, often overloaded, late classical decoration of which the Greek mainland was the most probable source (Cat. no. 242, Fig. 421).112

We have only three examples of Lydian anthemion stelai in which the shaft is even approximately preserved: the slender late archaic Cat. no. 47 (Figs. 153, 154) was perhaps 2.5 m. high, and the ratio of height to width better than 4:1; the unusual and still slender classical stele of Katovas (Cat. no. 240, Fig. 419; H. 1.79, W. 0.39) is about 4.5:1. For the bilingual stele Cat. no. 241 of 394 B.C., which is not quite complete (H. 1.63 + , W. 0.53; Fig. 420), the ratio may be 3.5:1. That the classical stelai were shorter and squatter is confirmed by a number of inscribed stelai.113 Particularly instructive is the stele, no. Cat. no. 22, found by the first Sardis expedition. Its height is two and two thirds times its width. When it was found, the tongue that would have been inserted into the socket of the base was still preserved.114

Unfortunately, the figured stelai of Sardis have not preserved their crowns, if they ever had them.115 Their history is discontinuous but illumines aspects and influences not represented in the surviving floral anthemia. There is no doubt that the earliest, that of Atrastas (Cat. no. 17, Figs. 70, 71), belongs to the lively Eastern Greek style of 520-500 B.C. It is unusual in having the small relief scene at the very top of the shaft. Broken at the top, the stele is 0.97 m. high, 0.32 m. wide (a ratio of ca. 3:1). The many examples for the motif of the seated men have been splendidly illustrated by E. Berger,116 while B. S. Ridgway has attributed to Eastern Greece stelai of the "Man and Dog" group and discussed the meaning of the motif,117 of which our stele presents an unusual variant with half the dog cut off. The man is envisaged as either reading or writing and this domestic theme with its attributes — the chair, the writing desk(?) — is part of a late archaic trend to depict the milieu, here given with provincial simplification. In addition to the examples cited by Ridgway, one should recall, for the mood of the times, Exekias' charming scene in which the Dioscurus, who has returned home, plays with his dog.118

A fragment in the Metropolitan Museum, brought in by the first Sardis expedition, is of great importance (Cat. no. 232, Fig. 402). It proves that the type of tall stele with a profiled late archaic or early classical male figure occupying the shaft119 was represented at Sardis. It also proves, despite poor preservation, that Sardian sculptors came in contact with that soft, nearly sentimental style which is best known through three tall "Man and Dog" stelai and which belongs to the years 490-460 B.C. The matter would be certain if one could substantiate the conjecture made by E. Pfuhl, who argued that the famous "Man and Dog" so-called Borgia stele in Naples, ca. 470-460 B.C., came from Sardis; unfortunately, the conjecture is poorly founded.120 Nevertheless, the figure style seems close to that of the Metropolitan Museum fragment,121 and the shape of the palmette of the anthemion with leaf-like lower termination of volute is the model of the type from which the volute of our stele Cat. no. 49 (Fig. 157) is derived.

The Greek model for the Metropolitan Museum stele could be either Attic, or Cycladic, or — if Eastern Greece is accepted as the provenance for the Borgia stele — Eastern Greek. With the poorly preserved votive(?) stele (Cat. no. 19, Figs. 75, 76, 77) of a veiled frontal woman and the provincial but fascinating stele of a priestess (Cat. no. 233, Fig. 403), we are definitely in the Cycladic-Boeotian ambient122 and past the mid-fifth century. A characteristic, classical feature of this group is the single figure with empty space around and overhead. The figure type of Cat. no. 19 itself recalls the so-called Aspasia (Europa).123 The tall profiled rise above the relief suggests a possible pedimental termination. The awkwardly placed figure of the woman in Cat. no. 233 is imitated from Greek models of the Cycladic-Boeotian group, but the rendering of her garment seems to be influenced by Persian palace reliefs, one of the few signs of Persian influence on lower level sculpture, perhaps conveyed by a Lydian who actually worked in Iran.124

Although its iconography is very local, the great Artemis-Cybele stele (Cat. no. 20, Figs. 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83) clearly confirms what the anthemion stelai had suggested: from the late fifth century on, Attic influence comes to the fore. Both in the wide format of the architectural frame with a pediment carried by Ionic piers and in the composition of the large goddesses and smaller votaries, the stimuli came from the Attic votive reliefs. This seems also true of the modest Cybele relief, which repeats the type of the famous Athenian image of Agorakritos (Cat. no. 21 Figs. 84, 85). Both works, one perhaps from the beginning, the other from the middle of the fourth century B.C., are executed in a somewhat halting imitation of Attic style.