Report 2: Sculpture from Sardis: The Finds through 1975 (1978)

by George M. A. Hanfmann

Chapter 3. The Sculpture of the Prehistoric, Lydian, and Persian Periods. Literary, Epigraphic, and Archaeological Evidence

Introduction

Literary sources for sculpture at Sardis during the Lydian and Persian periods are scanty. In the following are cited the relevant passages after Sardis M2 (1972), to which the reader is referred for the original Greek texts and commentary. The evidence from epigraphic sources consists of two dates provided by inscribed Lydian stelai and the dedication in Greek made by satrap Droaphernes.127

1. Meles and lion image. Sardis M2 (1972), no. 116 (Herodotus 1.84) and no. 114 (Favorinus De Fortuna 22). Capture of Sardis. “This was the only place where Meles, the earlier king of Sardis, did not carry the lion which his mistress bore him...the Telmessians [prophets] decreed that Sardis should be impregnable when the lion had been carried around the wall” (Herodotus). Meles, if historical, lived in the 8th C. B.C. The lion may have been a statue carried around the walls of the citadel in a ritual analogous to that of the Hittites. For lions, cf. Cat. nos. 7, 20, 26-36 (Figs. 28, 82, 102-133).

2. Gyges, gifts to Delphi. Sardis M2 (1972), no. 41 (Herodotus 1.14). "Gyges the king sent many gifts to Delphi...Most of his offerings there are of silver but he dedicated a great quantity of gold among which six golden mixing-bowl craters are the most worthy of mention. These stand in the treasury of the Corinthians and weigh thirty talents" (ca. 680-645 B.C.). The gold bowls may have been decorated with figures. The Lydians had no treasure house of their own at Delphi. The close relations to Corinth are reflected in sculpture, cf. Cat. no. 7 panels K and L (Figs. 42, 43).

3. Alyattes, gifts to Delphi. Sardis M2 (1972), no. 62 (Herodotus 1.25 and Pausanias 10.16.1-2). "Alyattes...died after a reign of fifty-seven years [617?-560 B.C.]. He was the second of his family to make an offering to Delphi...of a great silver bowl on a stand of welded iron. This is the work of Glaucus the Chian,128 the only man of that age who discovered how to weld iron." According to Hegesandros (in Athenaeus 210 C), the stand was decorated with little animals and plants. The passage proves that already Alyattes employed Greek Ionian artists.129

4. Alyattes, temples at Assessus. Sardis M2 (1972), no. 62 (Herodotus 1.22). Alyattes also built twin temples at Assessus in the Milesian territory. It is probable that they had some sculptural decoration. For a structure of the time of Alyattes with unusual sculptural decoration cf. Cat. no. 7 (Figs. 20-50).

5. Croesus (560-547 B.C.), presents to temple of Artemis, Ephesus. Sardis M2 (1972), no. 100 (Herodotus 1.92). “Croesus made many other dedications...at Ephesus the golden oxen and many of the columns.” The columns had reliefs and inscriptions in Greek and Lydian. “King Croesus gave (these),” “dedicated” in the Greek version. Pryce, nos. B 16, 32, B 50, 91, 103, figs. 32, 69. Hanfmann, Croesus, 11-14, figs. 21-22, 27-29, suggests that artists of a Sardo-Ephesian (Lydo-Ionian) school worked at both Ephesus and Sardis.

6. Croesus, presents to the oracle of Apollo in Delphi: lion. Sardis M2 (1972), no. 99 (Herodotus 1.50). The lion of pure (refined, “cooked”) gold, which originally weighed ten talents, was on a pedestal of 113 bricks of electrum (“white gold”), each of which was 6 by 3 by 1 (H.) palms and weighed two and a half talents; and four bricks of pure gold, each weighing two and a half talents. The lion, too, was in the treasury of the Corinthians (cf. supra no. 2 and infra no. 8). For possible reconstruction of the Delphi lion, see Elderkin, 1-8, fig. 1. The lion and its pedestal were melted down in the 4th C. B.C. Sardis M2 (1972), no. 98 (Diodorus 16.56.6). For lions of the Alyattes and Croesus eras, cf. Cat. nos. 23, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 37 (Figs. 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 102-124, 134) and the small gold lions, Sardis XIII (1925), no. 86, pl. 8.

7. Croesus, presents to Delphi: craters of gold and silver. Sardis M2 (1972), no. 99 (Herodotus 1.51). “The silver crater lies at the corner of the pronaos of the temple [of Apollo] and it holds six hundred amphoreis [nine gallon measures?]130 for the Delphians use it for the feast of the Divine Appearance [Theophania]. The Delphians say it is a work by Theodorus of Samos.”

The existence of huge mixing bowls in archaic Greece has been confirmed by the discovery of the mighty bronze crater of Vix (capacity 1200 liters; ca. 316 gallons). This passage proves that Theodorus of Samos, famous as architect of the huge Heraion of Samos, and as inventor and as bronze-caster of sculpture, was employed by Croesus. Like the crater of Vix, the silver crater of Theodorus may have been decorated with reliefs and figurines; Herodotus says “it seems to me to be of no common workmanship.” For the crater of Vix, cf. R. Joffroy, “Le tresor de Vix,” MonPiot 48 (1954) 1ff; Schefold, Die Griechen, 205-206, figs. 150 a-b; Hanfmann, Class. Sculpture, 312, figs. 90-91.

8. Croesus, presents to Delphi: four silver pithoi and two perirrhanteria ("sprinkling vessels"), one of gold and one of silver in treasury of the Corinthians. Sardis M2 (1972), no. 99 (Herodotus 1.51). "The figure of a boy, through whose hand the water runs...is a Lacaedemonian gift...but not either of the perirrhanteria." This sounds as if figurative work was involved. For the caryatid bowls supported by maidens and thought to be perirrhanteria, cf. Richter, Korai, 24, 27-30, figs. 35-56.

9. Croesus, statue of the woman who was his baker. Sardis M2 (1972), no. 68 (Plutarch De Pythiae oraculis 16 [401 E]) and no. 99 (Herodotus 1.51). Croesus' stepmother "gave poison to his baker and told her to knead it into the bread and give it to him. But the baker secretly told Croesus and gave the bread to the woman's children" (Plutarch). "Croesus sent...a golden image of a woman, three cubits [60 inches] high, which, the Delphians say, is the statue of the woman who was Croesus' baker" (Herodotus).

Apparently the statue had no identifying inscription or attributes. For Lydian korai of the time see the maidens on the sides of Cat. no. 7 (panels A, B, G-J, Figs. 33, 34, 39, 40, 41). The statue in Delphi was melted down in the 4th C. B.C. Sardis M2 (1972), no. 98 (Diodorus 16.56.6).

For a gold-silver bull, possibly a Croesan dedication, see P. Amandry, "Statue de taureau en argent," Études delphiques, BCH Supplement IV (1977) 273-293, esp. p. 291.

10. Sardians at work in Persian palaces at Susa and Persepolis. Sardis M2 (1972), nos. 302-303 (Darius, Persepolis H 3-10; Darius, Susa F 35-55). Building inscription of Darius, 530-485 B.C. “The stone cutters who wrought the stone, those were Sardians and Egyptians...The men who wrought the wood, those were Sardians and Egyptians.” New tablet from Susa, J. Perrot, CRAI (1970), 375-377. The Lydians may have learned from the Egyptians: a Lydian graffito was found in a quarry in Egypt, Gusmani, LW, no. 49.

Nylander, 14ff. and 138, n.355, 116f., admits the influence of Lydians in masonry but raises the question whether “to work the stone” and “to work the wood” included only masonry and carpentry or extended to relief and sculptural decoration. Tablet “Susa F” in Kent’s translation says: “The ornamentation with which the wall was adorned, that from Ionia was brought,” putting the Ionians into the rank of decorators. For the contacts of Lydia and Iran cf. Cat. nos. 16, 18, 231, 233 (Figs. 68, 69, 72, 73, 74, 401, 403).

11. Bronze statue of a water-carrying girl brought from Athens to Sardis (480-465 B.C.). Sardis M2 (1972), no. 274 (Plutarch Themistocles 31, possibly after Phainias of Eresos, pupil of Aristotle). "When he [Themistocles] had arrived at Sardis and having time for leisure went to see the arrangement of the sanctuaries and the great number of dedications, he saw in the sanctuary of the Mother [of the Gods] the statue called the water-carrier, a girl in bronze and two cubits high [ca. 40 inches]. When he was water commissioner in Athens he himself had this statue made...[It was carried off when the Persians captured Athens in 480 B.C.] He spoke to the satrap of Lydia asking him to send the statue back to Athens...The barbarian [perhaps Artaphernes II, cf. J. Keil, RE 26:2 (1927) 2175] got angry and threatened that he would write to the king," so the statue presumably stayed at Sardis.

The incident occurred after Themistocles was banished (468 B.C.) and before he went to the royal court at Susa (465 B.C.). The Greeks had burned down the temple of the Mother of the Gods (Cybele) in 499 B.C. The sanctuary was apparently functioning by 468-465 B.C. The notice shows that important early classical Greek originals were available as models for Sardian sculptors. For Themistocles as water commissioner, cf. M. Lang, Waterworks in the Athenian Agora (Princeton 1968), 3-4. For probable posture of the water-carrier, cf. Attic vases, Lysippides Painter, CVA British Museum VI, pl. 88. For early classical types comparable to a water-carrier, cf. basket-bearer, Paestum, Lamb 2, 143, pl. 51b (500-480 B.C.); Richter, Korai, 106-109, fig. 618. The style of the hydrophoros would have been Attic, of the time of the Euthydikos kore group, ibid., 98-104, nos. 180-188, figs. 565-599.

12. Image of Cybele, ca. 420 B.C.? In the famous lyric nome, The Persians, by the dithyrambic poet and composer Timotheos (performed ca. 419-416 B.C., according to C. M. Bowra, OCD 2, 1077) the Asia Minor vassals of Xerxes sing of their hope of return from Greece. After mentioning Sardis and Tmolus (verses 116-117; cf. Sardis M2 (1972), no. 190), they say that only the Great Goddess can save them, and wish “to fall at the knees of the Mother of the Mountains [Meter Oureia], the Mistress [Despoina] clad in the chiton with black leaves” (literally — to fall to the lordly knees, desposyna gonata, in black-leafed chiton, melampetalochitona). The speaker then invokes her as Divine Mother, Thea Meter, with the golden locks.

The natural assumption, now proposed by A. Henrichs, to whom we owe the knowledge of the passage (“Despoina Kybele,” HSCP 80 [1976], 435-503), is that the image of the Mountain Mother is that of Cybele or Kuvava. As a Mountain Mother she is linked with Dionysus (Baki in Lydian) in Euripides Bacchae 58, 72-81. Although a mountain goddess, Artemis does not qualify as Mother. Unfortunately, the passage does not indicate whether the goddess is envisaged as standing or seated, but we learn that the image had golden (gilded) locks and wore a chiton decorated with black leaves.

13. Image of Cybele, 409 B.C.? Sardis M2 (1972), no. 253 (Sophocles Philoctetes 391-401). “All Nourisher, Earth of the Mountains [orestera], Mother of Zeus himself, you who rule over the great Pactolus filled with gold, Lady Mother [Meter Potnia], Hail Blessed One, who sits on bull-slaying lions.”

In the light of our discovery of an altar of Kuvava on the Pactolus in the area of gold-purifying workshops (BASOR 191, 11-12, figs. 9-11; BASOR 199, 22; Hanfmann-Waldbaum, “New Excavations”, 311-315; Hanfmann, Letters, 222-234, figs. 169, 176; idem, Croesus, 14, figs. 31-32; Sardis M3 [1974], 28-30), it seems permissible to interpret the reference as an allusion to an actual image of Cybele seated either upon or between lions (as would be the case with the “Agorakritos type,” cf. Cat. no. 21 Figs. 84, 85). It is noteworthy that Sophocles equates Cybele and Mountain Mother with Mother Earth; this may explain the later equation with Demeter in Apollonius of Tyana (see Penella, 308 text, 311 commentary).

14. The altar of Artemis. Sardis M2 (1972), no. 271 (Xenophon Anabasis 1.6.6-7). The Younger Cyrus and Orontas swore oaths of friendship, between 407 and 401 B.C. For an ornament possibly from the altar, cf. Cat. no. 51 (Fig. 161). The excavators record an archaic altar of the 6th C. B.C., probably decorated, and a late Achaemenid 4th C. enlargement, cf. Sardis R1 (1975), Ch. 6, “The Artemis Altars LA 1 and LA 2.”

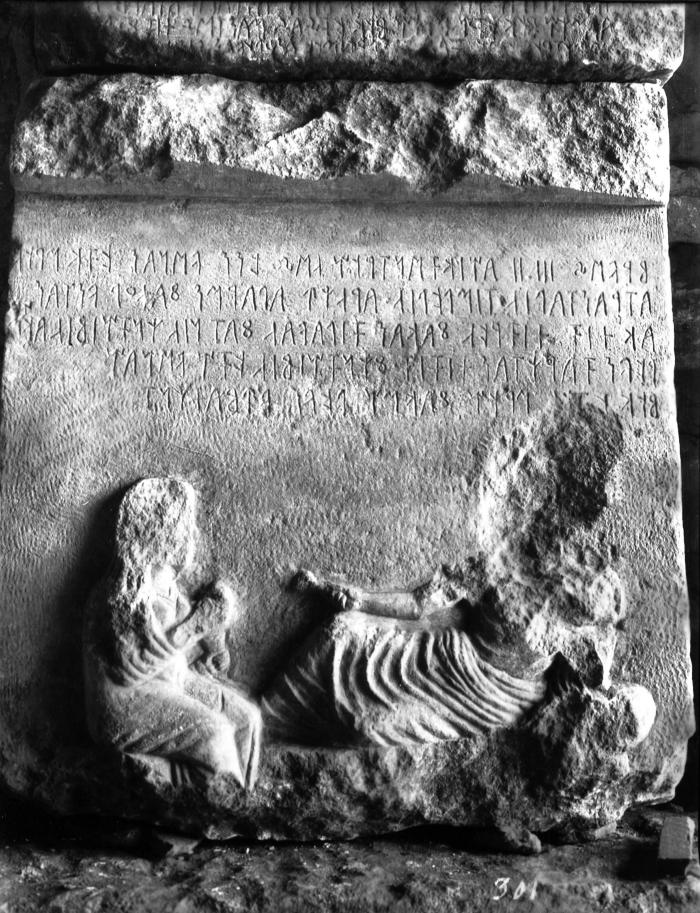

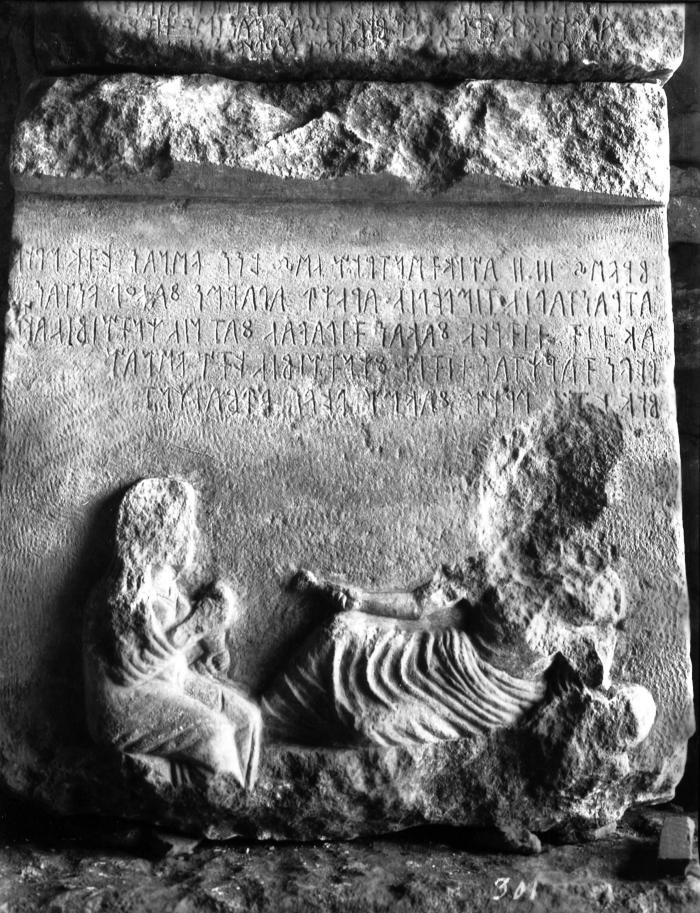

15. Stele with palmette finial, dated 394 B.C., Aramaic-Lydian bilingual. Here Cat. no. 241 (Fig. 420). The date is preserved in the Aramaic text. “On the fifth of Marhesuan of year 10 of Artaxerxes the King. In Sardis the fortress.” Both texts threaten: “Whoever damages this stele of this grave chamber of this dromos...to him Artemis of Ephesus and Artemis of Koloe...shall bring destruction.”

Sardis VI.2 (1924), no. 1; Gusmani, LW, no. 1; idem, "Lydiaka", 272. Only Artaxerxes II Mnemon (436-358 B.C.) who began to rule in 404 B.C. is possible on the grounds of the style of the finial.

16. Inscribed statue base, 366-365 B.C., dated in the 39th year of the rule of Artaxerxes II Mnemon. Here Cat. no. 273 (Figs. 463, 464). Droaphernes, “son of Barakes, satrap of Lydia, erected the statue to Zeus Baradates.”

The dedicatory inscription was copied in Roman times, according to L. Robert not earlier than the 2nd C. A.D., and this copy was found built into a late Roman wall on the Pactolus. It is not known whether the statue showed the god in Greek-Lydian style, as Zeus Lydios was shown on coins (cf. for instance, Métraux, 158, pl. 36:8-9) or in the Persian likeness of Ahura Mazda, known from gold plaques and Perso-Lydian seals (cf. Sardis XIII [1925], 13, pl. 8, no. 8, Tomb 27-A). The inscription is published by L. Robert, CRAI (Apr.-June 1975), 306-330, figs. 1-2. Cf. AJA 79 (1975), 216, pl. 42:18-19; AASOR, forthcoming.

17. Stele with funerary meal, dated by Lydian inscription. Here Cat. no. 234 (Fig. 404). “In the year 5 under Alexander”: 330-329 B.C. counting from the conquest of Asia Minor in 334 B.C. The stele belonged to Atrastas (Adrastos), son of Timles. “Whosoever damages this grave or this stele him Levs [Zeus] will destroy.” Sardis VI.2 (1924), no. 3; Gusmani, LW, no. 3.

18. Statue of a Lydian named Adrastos, 323-322 B.C.(?). Sardis M2 (1972), no. 270 (Pausanias 7.6.6). “A Lydian, Adrastos by name aided the Greeks [in the Lamian War] but privately and not at the instructions of the Lydian state. But the Lydians set up a bronze statue of Adrastos in front of the sanctuary of the Persian Artemis, and they wrote an epigram saying that Adrastos died fighting for the Greeks against Leonnatos.”

This was a portrait statue probably of a warrior (cf. the contemporaneous portrait of the warrior Aristonautes, ca. 320 B.C., A. von Salis, Das Grabmal des Aristonautes. Winckelmannsprogramm der Archaologischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin 84 [1926], pls. 1-2). The name Adrastos (Atrastas) was very popular in Lydia and nothing further is known about this particular Adrastos. The “Persian Artemis” is Artemis Anahita, whose cult was introduced in Lydia by Artaxerxes II. There is no evidence to indicate whether this shrine of Anahita was different from the Artemis sanctuary in the Pactolus Valley, of which the altar and Hellenistic-Roman temple is preserved. The poem may have been bilingual, Lydian and Greek, like the dedication by Nannas Dionysikleos (Cat. no. 274, Figs. 465, 466). Evidently the Lydians closely followed the Greek lead in introducing honorary statues. Pausanias makes it sound as if the Lydian state set up the statue. The statue of Demosthenes set up in Athens in 280 B.C. was a similar anti-Macedonian demonstration. After capture of Sardis in 334 B.C., Alexander told the Lydians that they would be free “to use their own laws,” i.e. to have nominal independence. They reckoned the date by his reign in 329 B.C. During the time between the death of Alexander (323 B.C.) and the battle of Kyroupedion (281 B.C.) Sardis was within the Macedonian sphere, but during this period of tumultuous changes actual control may have varied considerably. Theoretically the statue, celebrating Adrastos because he fought against the Macedonians, could have been set up only after the Seleucids took over in 281 B.C.

19. Gilded bronze statues of Apollo, Artemis, and Herakles by the sculptors Dipoinos and Skyllis taken from Croesus by Ardashir (Cyrus). E. Sellers, The Elder Pliny’s Chapters on the History of Art, trans. K. Jex-Blake (London 1896), 184-185, citing Moses of Chorene 2.12.

Sellers’ reading of Moses of Chorene implies that the statues were at Sardis, but up-to-date commentary by R. W. Thomson (letter Mar. 7, 1977; see Moses Khorenats ‘i, History of the Armenians, trans, and ed. R. W. Thomson [Cambridge, Mass. 1978]) makes it clear that one cannot be sure the pieces in question came from either Sardis or Lydia rather than from some other site in the area of the later province of Asia.

-

Fig. 28

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine," detail with possible outline of lion. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 82

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers, detail of Cybele. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 102

Lion couchant, left side. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 133

Acroterion (?), small recumbent lion from corner of archaic sarcophagus lid? (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 42

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine," Panel K. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 43

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine," Panel L. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 20

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine" (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 50

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine," Panel R. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 87

Double-sided relief with archaic lion sejant, side view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 88

Double-sided relief with archaic lion sejant, side view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 89

Double-sided relief with archaic lion sejant, top view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 90

Head and neck of lion sejant. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 91

Head and neck of lion sejant. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 124

Lion's right foot on plinth. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 134

Lion's paw. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 33

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine," Panel A. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 34

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine," Panel B. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 39

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine," Panel H. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 40

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine," Panel I. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 41

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine," Panel J. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 68

Two-sided relief fragment with folds or feathers. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 69

Two-sided relief fragment with folds or feathers. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 72

Part of a pediment. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 73

Part of a pediment, detail of ornament. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 74

Part of a pediment, projection drawing of pediment block. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 401

Frieze of horsemen, British Museum B 269. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 403

Stele with praying woman, Izmir Archaeological Museum 690 (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 84

Relief of Cybele seated with lion in her lap and at her feet. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 85

Relief of Cybele seated with lion in her lap and at her feet, 3/4 view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 161

Fragment of sima frieze? (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 420

Anthemion with Lydian-Aramaic bilingual, stele of Manes, son of Kumlis, Izmir Archaeological Museum 691. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 463

Dedication of an image of Zeus Baradates. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 464

Dedication of an image of Zeus Baradates, top and back. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 404

Funerary stele of Atrastas, son of Timles, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4030 (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 465

Bilingual dedication of Nannas Bakivalis to Artemis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 466

Bilingual dedication of Nannas Bakivalis to Artemis, top. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

Findspots and Original Positions

The findspots of the Lydian and Persian sculpture from Sardis may be divided into three categories. Those which are uninformative are in the great majority, such as the archaic sculpture reused in walls and foundations as, for instance, the archaic Manisa kore in a Roman wall (Cat. no. 8, Figs. 51, 52, 53, 54) or the “laughing lion” (Cat. no. 26, Figs. 102, 103, 104) built into the foundation of a Synagogue pier. The classical reliefs Cat. nos. 19 and 20 (Figs. 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83) were used face down in the stylobate of the forecourt colonnade in the Synagogue; Cat. nos. 4, 6, and 7 (Figs. 11, 12, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20-50) were used as masonry in the piers (4 perhaps in the wall). The half-pediment of the Persian period (Cat. no. 18, Figs. 72, 73, 74) was apparently also reused in a Roman structure. Even most of the Lydian funerary stelai were found in a secondary terrace wall (Sardis VI.2 [1924], 1, cf. Cat. no. 241, Fig. 420).

In a few cases, something can be deduced from the findspot. The stele Cat. no. 9 (Figs. 58, 59, 60) was found near the site of a small sanctuary (Dede Mezarı), the lion spout Cat. no. 237 (Figs. 410, 411, 412) at the northeast corner of the Artemis Temple, the palmette-lotus Cat. no. 51 (Fig. 161), though not stratified, within the area of the Artemis altar. The fine stele fragment Cat. no. 46 (Figs. 150, 151) was found near the Lydian tombs of Şeytan Dere.131

A chronological indication but no information about the original use comes from the stratified black lava piece found at PN (Cat. no. 16, Figs. 68, 69). It was associated with a floor at furnace B which, according to A. Ramage, dates to the second quarter of the sixth century B.C.132

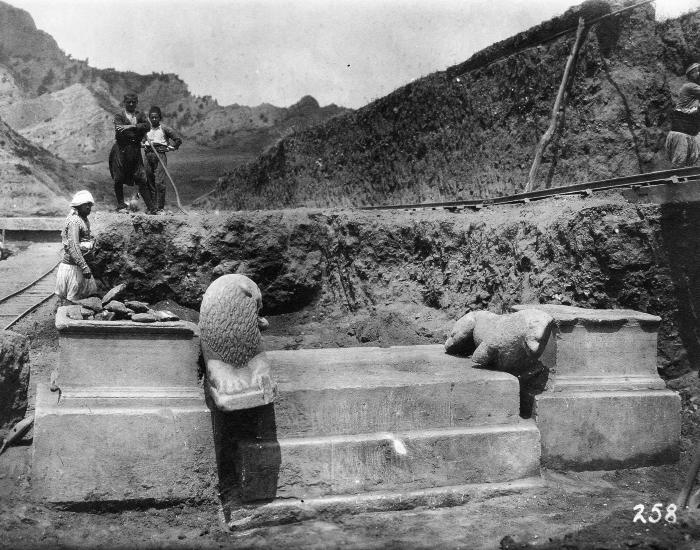

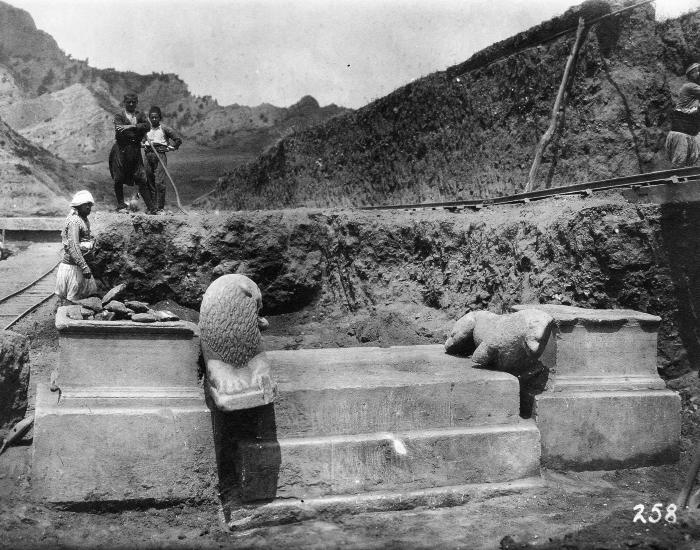

Finally, for the third group, the two and one half lions found immured in the altar of Kuvava at PN (Cat. nos. 27, 28, 29, Figs. 105-117) constitute the only statues of the Lydian period that were possibly found in their original positions. The stratigraphy of PN and of the gold refinery area has been somewhat revised by A. Ramage, who has kindly made available his preliminary conclusions.133 The altar, according to Ramage, did not contain any datable sherds in the sacrificial layers that were found in it. The cobbled floor of the sacrificial surface within the altar was above the industrial debris; according to A. Ramage (letter, Feb. 1972) “the sherds [in the debris] are almost certainly connected with industrial activities, perhaps from furnace C, about which hardly anything has been written.” At any rate, the sherds did get into the fill in the lower part of the altar, and thus provide a terminus post quem.134

Pending closer dating by ceramic experts, 570-560 B.C. is a plausible date for construction of the altar. On this basis, the lions would date into the rule of Alyattes (617-560 B.C.). This phase is shown in our reconstruction of the altar, Figure 106.

The altar was then damaged by flood. According to the excavator, “an addition to its western side rests on a heavy deposit at *87.55.”135 The altar was made 0.60 m. higher, and “during the reconstruction, two nearly complete archaic lions and a half lion, intentionally cut, were carefully surrounded by schist and small limestone chips and immured at the southeast, southwest, and northwest corners.” There are no finds that would help to date closely this reconstruction of the altar. A. Ramage writes, “I have the feeling that the altar was not used for very long in Phase I — the clay ‘floor’ around it is not very thick (0.15 m.) and the thin surface between two gravel layers even thinner. Phase II would seem to be even shorter.” This would make it possible to retain the suggestion advanced in 1967 that the rebuilding took place after 547 B.C., under the Persians who preferred a noniconic altar. A. Ramage by letter also considers that the altar could have been exposed but not in use into the fifth century, since there was a small structure and a marbled lekythos found within the gravel nearby.

The attribution to the goddess Cybele (Kuvava) has been reinforced by the find of a Lydian graffito in a dump nearby, W266-267/S344-347 *86-85.5, in a level that belongs to the refinery but is earlier than the altar.136

For the funerary sculpture, we know the original position of the stele Cat. no. 47 (Figs. 153, 154) at the entrance to Tomb 813, but the stele itself is lost and the position of the grave cannot be identified.137

The great array of archaic and classical monuments reused in the Synagogue calls for an explanation. The archaic goddesses or korai Cat. no. 4 and 6 (Figs. 11, 12, 16, 17, 18, 19), the extraordinary Ionic shrine model Cat. no. 7 (Figs. 20-50), as well as a number of fine Ionic architectural fragments,138 might belong to an archaic sanctuary; the pairs of lions Cat. no. 25 (Figs. , 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101) and the stelai Cat. nos. 19 and 20 (Figs. 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83) would belong to its classical phase. To this classical phase, too, must be assigned the marble blocks from the parastades of the Metroon (Temple of Mother, that is, of Cybele) with inscriptions dated in 213 B.C. which were reused in the piers of the Synagogue.139 Thus, one might speculate that much of the sculpture came from a sanctuary or the sanctuary of Cybele. Against this hypothesis one may argue that sculpture from non-Cybele contexts has been found in the Synagogue.140 Also, one would expect the archaic sculpture to show signs of fire damage, since the Greeks burned down the temple of Cybele in 499 B.C. (Herodotus 5.102), but this is not the case. The inscribed blocks from the Metroon show no signs of burning, but they are later than 499 B.C. and belong to a reconstruction of the classical period.141 Knowing the location of the great temple and precinct of Cybele (Metroon) would be invaluable; unfortunately we have found no evidence to show that they were located near the freestanding archaic altar to Cybele described above (Figs. 105, 106).

The monument with the inscription of the satrap Droaphernes, dated 366-365 B.C., may have carried original sculpture of the Persian period, such as the image of Zeus Baradates (supra, no. 16) but its inscription was written in Roman times on what appears to be a marble block from a Roman restoration (Cat. no. 273, Figs. 463, 464). The block was, in turn, reused in a late Roman villa on the Pactolus.

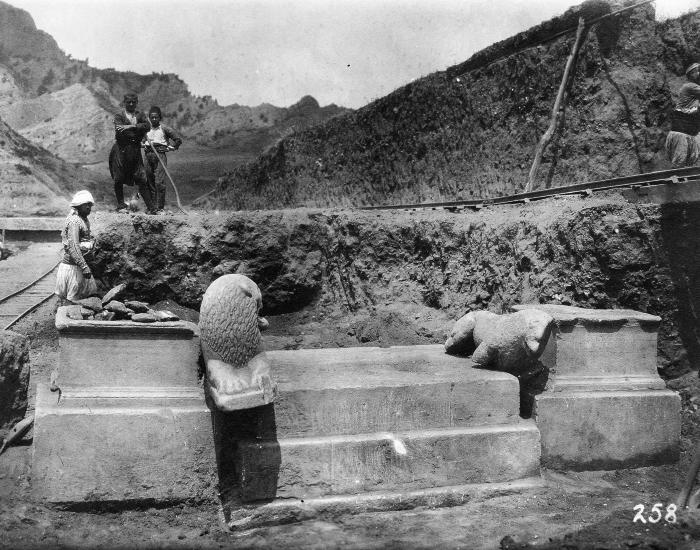

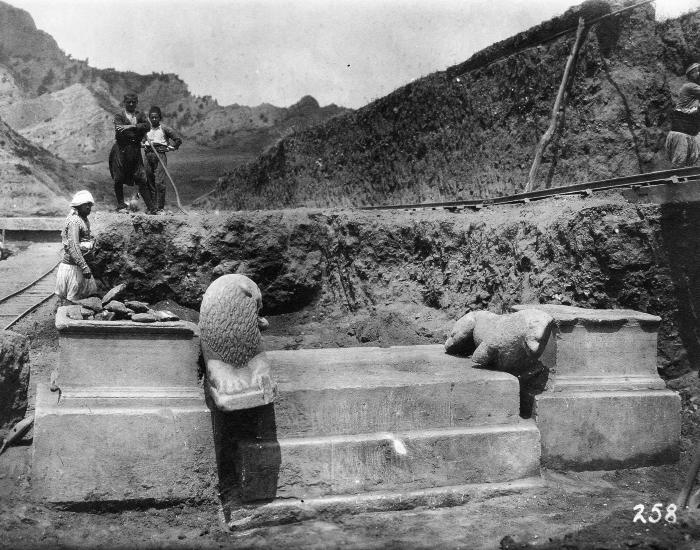

Even more complicated was the fate of the base dedicated in Lydian and Greek to Artemis by Nannas. Dated in the fourth century B.C., the base was found in the Artemis Precinct but not in its original position.142 It had been reset by the Romans, who also combined it with other bases and installed two archaic lions and a bird of prey on the newly created monument (Cat. nos. 235, 236, 238, 274, Figs. 405, 406, 407, 408, 409, 413, 414, 415, 465, 466).

To the same Roman restoration of the Artemis Precinct must be assigned the arrangement of Lydian and Greek stelai in two rows converging upon the western facade of the temple and surrounding the later Artemis altar (LA 2).143 While these findspots create a presumption that the stelai came from the Artemis Precinct, they convey nothing about the original positions.

-

Fig. 51

"Mantle-Wearer," kore (?) Manisa 325, front. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 52

"Mantle-Wearer," kore (?) Manisa 325, right side. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 53

"Mantle-Wearer," kore (?) Manisa 325, back. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 54

"Mantle-Wearer," kore (?) Manisa 325, left side. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 102

Lion couchant, left side. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 103

Lion couchant, right side. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 104

Lion couchant, detail. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 75

Stele with veiled frontal female. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 76

Stele with veiled frontal female, L. side. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 77

Stele with veiled frontal female, detail. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 78

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 79

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers, reconstruction drawing of naiskos. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 80

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers, 3/4 view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 81

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers, detail of Artemis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 82

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers, detail of Cybele. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 83

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers, detail of two worshippers. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 11

Lower part of Archaic kore, "North kore" (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 12

Lower part of Archaic kore, "North kore," side view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 16

Fragment of a goddess holding a snake (?) standing in columnar shrine, "South kore." (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 17

Fragment of a goddess holding a snake (?) standing in columnar shrine, "South kore," tentative restoration. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 18

Fragment of a goddess holding a snake (?) standing in columnar shrine, "South kore," actual state and schematic restoration (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 19

Fragment of a goddess holding a snake (?) standing in columnar shrine, "South kore," column fragment. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 20

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine" (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 50

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine," Panel R. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 72

Part of a pediment. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 73

Part of a pediment, detail of ornament. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 74

Part of a pediment, projection drawing of pediment block. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 420

Anthemion with Lydian-Aramaic bilingual, stele of Manes, son of Kumlis, Izmir Archaeological Museum 691. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 58

Relief of frontal standing draped female figure. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 59

Relief of frontal standing draped female figure, detail. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 60

Relief of frontal standing draped female figure, drawing. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 410

Lion spout attached to rectangular member. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 411

Lion spout attached to rectangular member, detail of lion. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 412

Lion spout attached to rectangular member, drawing with elevations, top view, and section. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 161

Fragment of sima frieze? (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 150

Fragment of anthemion. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 151

Fragment of anthemion, detail. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 68

Two-sided relief fragment with folds or feathers. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 69

Two-sided relief fragment with folds or feathers. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 105

Restored altar at PN with casts of lions 27 (S67.016), 28 (S67.032), and 29 (S67.033) in place, looking S. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 117

Recumbent lion on plinth, SW corner of altar, in situ. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 106

Isometric reconstruction drawing of altar at PN, first building phase, showing tentative position of lions. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 153

Chamber tomb stele, now lost. Plan and elevation of chamber tomb (Tomb 813) showing placement of stelai (From Sardis I (1922) ill. 178) ()

-

Fig. 154

Chamber tomb stele. ()

-

Fig. 92

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lions A and B. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 93

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lion B. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 94

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lion B. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 95

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lions C and D in situ near Synagogue apse. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 96

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lions D and C. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 97

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lions D and C after restoration. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 98

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lions C and D after restoration. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 99

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lion C. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 100

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lion C, right profile. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 101

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lion A from above. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 463

Dedication of an image of Zeus Baradates. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 464

Dedication of an image of Zeus Baradates, top and back. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 405

Lion sejant from Nannas monument, Metropolitan Museum of Art 26.59.9, left profile. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 406

Lion sejant from Nannas monument, Metropolitan Museum of Art 26.59.9, back. (Photograph courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Gift of The American Society for the Excavation of Sardis, 1926)

-

Fig. 407

Recumbent lion from Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4028, shown as excavated by the first Sardis expedtion, front. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 408

Recumbent lion from Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4028, shown as excavated by the first Sardis expedtion, back. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 409

Lion sejant and recumbent lion from Nannas monument, in situ. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 413

Bird of prey (eagle?) holding a hare, from the Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4032. ()

-

Fig. 414

Bird of prey (eagle?) holding a hare, from the Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4032, three-quarter view. ()

-

Fig. 415

Bird of prey (eagle?) holding a hare, from the Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4032, back. ()

-

Fig. 465

Bilingual dedication of Nannas Bakivalis to Artemis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 466

Bilingual dedication of Nannas Bakivalis to Artemis, top. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

Manner of Display and Function

If the sculptured lions of the Kuvava altar (Cat. nos. 27, 28, 29, Figs. 105-117) were in situ when found (supra) then they had no special separate bases. From the parallel of the lion-crowned fountain of the Tomba dei Tori one may assume that at Sardis, as at the Etruscan (or Eastern Greek) painter's Troy, the altar was stuccoed and gaily painted.144 Presumably there were originally four lions; as expressions of the might of the goddess they were roaring eastward, toward the rising sun.

The way the Romans used the great lion Cat. no. 31 (Figs. 119, 120, 121, 122) in an architectural-heraldic context, and the fact that it had a counterpart (Cat. no. 32, Fig. 123) suggest that these were originally two flanking lions (flanking a gate?). There are many precedents for flanking lions in "Late Hittite" gates;145 however, the placement of the Sardis lions, with their heads facing, their bodies seen in profile, recalls Assyrian gate bulls and Mesopotamian and Egyptian lion statues.146

Given the large number of lions found at Sardis (22 are catalogued), one may conjecture that they were arrayed along a sacred road or roads like the lions of Apollo along the road from Didyma to Panormus,147 or placed in file on a terrace like the lions in the Letoon of Delos.148

The very existence of two similar pairs of double lions, found in the Synagogue, intimates that they may have originally flanked an image (Cat. no. 25, Figs. 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101) just as in their later incarnation they flanked the altar-like table in the Synagogue.149

The double-sided relief of an archaic lion (Cat. no. 23, Figs. 87, 88, 89) and two double-sided sphinx reliefs (Cat. nos. 42, 239, Figs. 144, 145, 416, 417, 418) were parts of marble thrones. The early archaic lion was found in a cistern on the Acropolis; thus there is at least a possibility that he belonged to the royal palace, now thought to have been located on the citadel.150

The evidence is less clear for female and male figures. The little standing korai-priestesses (Cat. nos. 4, 5, Figs. 11, 12, 13, 14, 15) were set into small bases and placed against a backing element, possibly within a shrine. They were votives, as were the shrine-like representations with the snake-goddess and Cybele (Cat. nos. 6, 7, Figs. 16-50).

There is a tantalizing possibility that despite her small size (max. H. ca. 0.30, head and crown 0.07), the goddess with polos, possibly the earliest of all the archaic marble sculpture (Cat. no. 3, Figs. 9, 10), actually served as an early archaic image in a shrine of Artemis or Cybele (or another goddess). She is, at any rate, a close reflection of such an image.151

The Cybele of the shrine-model (Cat. no. 7, Fig. 20) is quite certainly a reflection of an actual archaic image seen in a temple; and the same assumptions may be made for the snake-holder (Cat. no. 6, Fig. 16), who may be imagined as standing in a smaller shrine and who probably represents a goddess, not a devotee.

If one takes literally the relief with Artemis and Cybele (Cat. no. 20, Figs. 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83), then one might assume that they are envisaged as two classical images standing together on one low base. This, in turn, would lead to the more doubtful assumption that the two at some point were worshipped together in one sanctuary.152

Another image type of Cybele, the famous seated one, is seen in the classical relief Cat. no. 21 (Figs. 84, 85). The piece is also of interest because it was fastened to some architectural frame, but whether this frame was on the inside or the outside of a stone structure we have no way of telling.

An interesting problem is posed by the rectangular marble pier or base that bears an inscription in an unknown tongue (Cat. no. 272, Fig. 462). Perhaps this is the right (from the spectator's point of view) projecting part of a Pi-shaped monument, which might have carried a statuary group with two symmetrical flanking figures (for instance, two horsemen) and one or more figures in the center; but R. Gusmani suggests that the structure was an altar.153 Examples of late profiled, rather low (H. 0.44; W . 0.79; Th. 0.68) classical statue bases, possibly placed on a lower stone base, survive in the base with the inscription of Nannas (Cat. no. 274, Figs. 465, 466) and its counterpart, both with nice top and bottom profiles. At least one carried a bronze statue. Again, their original places are unknown.

We have mentioned the many bases for stelai found in the Artemis Precinct. While they were arranged in their present positions during Roman times, the technical and epigraphic evidence suggests that they date from the fifth, fourth, and possibly third centuries B.C. Several of the bases show original cuttings for stelai. The general type of the votive stele monument may be restored as consisting of a larger base, partly set into the ground, and an upper base with an oblong cutting for the stele. Only one inscribed Lydian stele was found fallen next to its probable base.154 The workmanship of the extant stelai bases is very homogeneous, precise, and advanced, with much use of multiple claw chisel.155

The clearest evidence for the original setting concerns the funerary stelai. The invaluable report and photograph by H. C. Butler156 prove that the stele Cat. no. 47 (Figs. 153, 154) and its counterpart flanked the stair going up to the rock-cut tomb chamber of Tomb 813. In several other instances the stelai were fastened nearly flush against the wall of the rock, into which the chamber tombs were cut. None of the fragments collected by our expedition were in situ, but one was found near a grave (Cat. no. 46, Figs. 150, 151), and the beautiful anthemion Cat. no. 45 (Figs. 148, 149) was not far from a group of Lydian rock-cut tombs. There is no instance to show how the figured stelai were placed, but the condition of the Atrastas stele (Cat. no. 17, Figs. 70, 71) indicates that they, too, were fastened at the top to a back wall. Indeed, this type of fastening has been used as an argument to attribute to Sardis the famous Borgia stele in Naples, a very fine early classical work.157

Of the architectural sculpture, the small pediment of the Persian era (Cat. no. 18 Figs. 72, 73, 74) can be shown to belong to a temple-tomb mausoleum best known from the Nereid Monument from Xanthos.158 The beautifully worked, possibly imported relief fragment Cat. no. 22 (Fig. 86) showing the body of an animal (leopard or dog?) is closely parallelled in another frieze at Xanthos assigned to complex G and dated ca. 460 B.C.159 The Sardis frieze would have been over two feet high. It too may have belonged to a temple-like mausoleum or heroon.

Otherwise, the profusion of friezes suggested by the three superposed zones of reliefs on the Cybele shrine (Cat. no. 7, Figs. 20-50) is not reflected in the actual finds. The two small archaic friezes from Bin Tepe probably decorated funerary couches (Cat. nos. 230, 231, Figs. 400, 401); another very small frieze of lions (Cat. no. 39, Figs. 137, 138) may have been part of an architectural frame of a small shrine of Cybele. Finally, a relief with bull and lion (?) might also have belonged to a frieze (Cat. no. 44, Fig. 147).

Thus, if we consider the sacral functions of sculpture, we find that an outdoor, freestanding altar was decorated with lions (Cat. nos. 27, 28, 29, Figs. 105-117); we may have a fragment in the round of a very early archaic marble image (Cat. no. 3, Figs. 9, 10) of a goddess; and we probably have the flanking lion groups of a Cybele image of classical date (Cat. nos. 25, Figs. 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101). Reflections of other temple images of archaic and classical times (Cybele, snake goddess?, Artemis, Aphrodite?, Kore?) are also known, but it is not known whether they were of marble.

As to the shrines, we have representations of a more elaborate temple (Cat. no. 7, Figs. 20-50) and of a simpler naiskos, with two columns (Cat. no. 6, Figs. 16, 17, 18, 19). The Cybele shrine of ca. 560 B.C. shows three superposed friezes of figures; it is probable that the lightly raised figures are envisaged as marble reliefs. Actual decorative parts of archaic Ionic marble buildings of ca. 500 B.C. survive.160 The earliest extant architectural piece of marble sculpture from a temple-like structure is probably the imported (?) fragment with a leopard (Cat. no. 22, Fig. 86, ca. 500 B.C.) from a frieze. The structure may have been a temple-like mausoleum or heroon. The pediment of the late fifth century B.C. with the funerary meal (Cat. no. 18, Figs. 72, 73, 74) also belongs to such a temple-like heroon.

The series of votives begins with early archaic priestesses and goddesses in shrines of unknown locations (Cat. nos. 4, 5, 6, Figs. 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19). We can envisage, however, something of the votives in the Artemis Precinct of archaic and classical times. They probably included marble lions and a bird of prey (Cat. nos. 235, 236, 238, Figs. 405, 406, 407, 408, 409, 413, 414, 415) and a considerable number of stelai with floral and probably with figurative (classical) reliefs and inscriptions. As far as the preserved material goes, both bases and sculpture, it looks as if votive stelai were more frequent than statues. Only one statuary base, that of Nannas, has a Lydian inscription.161

None of the sculpture can be referred with certainty to the palace or to public buildings. If the big lions served as guardians of the gate (Cat. nos. 31, 32, Figs. 119, 120, 121, 122, 123), they might have guarded an entrance in the palace — but equally an entrance to a sanctuary. The fragment of an archaic lion throne (Cat. nos. 23, Figs. 87, 88, 89) found close to the conjectural area of the palace,162 might have come from a royal marble throne.

In the cemeteries of Sardis funerary stelai with floral anthemia, and very probably figured stelai also, adorned the entrances to the rock-cut chamber tombs. Inside the chambers within the mounds of Bin Tepe and in other suburban burial grounds,163 limestone and marble couches (and perhaps thrones) were occasionally decorated with small figured friezes (Cat. nos. 230, 231, Figs. 400, 401). Markers, often thought to be phallic, crowned the mounds.164

One might, in the end, point to some uncertainties. The only sizable archaic human figure in the round, the statue in Manisa (Cat. no. 8, Figs. 51, 52, 53, 54), was found built into a Roman wall; we do not know whether it was a dedication or a funerary statue; of the latter, we have, so far, no certain example.

Then again, of all the many lions found, none has been clearly associated with a grave, though the lion as guardian of the grave is not unknown in archaic Asia Minor.165 This may be due to chance, but for the time being it looks as if stelai of marble were more popular than statuary as sepulchral monuments at Sardis.

Only a few items may be considered as possible domestic furnishings. The relief of a seated Cybele (Cat. no. 21, Figs. 84, 85) and the frame with walking lions (Cat. no. 39, Figs. 137, 138) might come from small devotional shrines within houses, and the late sphinx relief (Cat. no. 42, Figs. 144, 145) may have supported a marble chair of the kind that have been found in Pompeian dwellings.166

-

Fig. 105

Restored altar at PN with casts of lions 27 (S67.016), 28 (S67.032), and 29 (S67.033) in place, looking S. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 117

Recumbent lion on plinth, SW corner of altar, in situ. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 119

Large recumbent lion, left side. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 120

Large recumbent lion, right side. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 121

Large recumbent lion, front. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 122

Large recumbent lion, detail. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 123

Fragment of colossal lion's foot. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 92

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lions A and B. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 93

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lion B. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 94

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lion B. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 95

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lions C and D in situ near Synagogue apse. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 96

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lions D and C. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 97

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lions D and C after restoration. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 98

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lions C and D after restoration. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 99

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lion C. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 100

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lion C, right profile. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 101

Pair of addorsed lions sejant, Lion A from above. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 87

Double-sided relief with archaic lion sejant, side view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 88

Double-sided relief with archaic lion sejant, side view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 89

Double-sided relief with archaic lion sejant, top view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 144

Sphinx, probably from a throne, Manisa 21, left side. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 145

Sphinx, probably from a throne, Manisa 21, front. ()

-

Fig. 416

Sphinx, presumably part of a throne or seat, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4031, left profile. ()

-

Fig. 417

Sphinx, presumably part of a throne or seat, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4031, right profile. ()

-

Fig. 418

Sphinx, presumably part of a throne or seat, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4031, front. ()

-

Fig. 11

Lower part of Archaic kore, "North kore" (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 12

Lower part of Archaic kore, "North kore," side view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 13

Lower part of small Archaic kore. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 14

Lower part of small Archaic kore, side view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 15

Lower part of small Archaic kore, back view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 16

Fragment of a goddess holding a snake (?) standing in columnar shrine, "South kore." (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 50

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine," Panel R. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 9

Small crowned female head, front. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 10

Small, crowned female head, profile view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 20

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine" (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 78

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 79

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers, reconstruction drawing of naiskos. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 80

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers, 3/4 view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 81

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers, detail of Artemis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 82

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers, detail of Cybele. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 83

Stele with Artemis, Cybele, and two worshippers, detail of two worshippers. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 84

Relief of Cybele seated with lion in her lap and at her feet. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 85

Relief of Cybele seated with lion in her lap and at her feet, 3/4 view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 462

Marble block with inscription in unknown language. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 465

Bilingual dedication of Nannas Bakivalis to Artemis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 466

Bilingual dedication of Nannas Bakivalis to Artemis, top. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 153

Chamber tomb stele, now lost. Plan and elevation of chamber tomb (Tomb 813) showing placement of stelai (From Sardis I (1922) ill. 178) ()

-

Fig. 154

Chamber tomb stele. ()

-

Fig. 150

Fragment of anthemion. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 151

Fragment of anthemion, detail. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 148

Anthemion (finial). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 149

Anthemion (finial), back. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 70

Inscribed stele with seated man (Atrastas, son of Sakardas), Manisa 1. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 71

Inscribed stele with seated man (Atrastas, son of Sakardas), Manisa 1, detail. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 72

Part of a pediment. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 73

Part of a pediment, detail of ornament. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 74

Part of a pediment, projection drawing of pediment block. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 86

Fragment of Archaic relief with part of running animal. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 400

Frieze with grazing deer, British Museum, B 270. ()

-

Fig. 401

Frieze of horsemen, British Museum B 269. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 137

Part of frame with walking lion. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 138

Part of frame with walking lion. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 147

Relief fragment with rearing animal. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 17

Fragment of a goddess holding a snake (?) standing in columnar shrine, "South kore," tentative restoration. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 18

Fragment of a goddess holding a snake (?) standing in columnar shrine, "South kore," actual state and schematic restoration (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 19

Fragment of a goddess holding a snake (?) standing in columnar shrine, "South kore," column fragment. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 405

Lion sejant from Nannas monument, Metropolitan Museum of Art 26.59.9, left profile. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 406

Lion sejant from Nannas monument, Metropolitan Museum of Art 26.59.9, back. (Photograph courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Gift of The American Society for the Excavation of Sardis, 1926)

-

Fig. 407

Recumbent lion from Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4028, shown as excavated by the first Sardis expedtion, front. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 408

Recumbent lion from Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4028, shown as excavated by the first Sardis expedtion, back. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 409

Lion sejant and recumbent lion from Nannas monument, in situ. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 413

Bird of prey (eagle?) holding a hare, from the Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4032. ()

-

Fig. 414

Bird of prey (eagle?) holding a hare, from the Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4032, three-quarter view. ()

-

Fig. 415

Bird of prey (eagle?) holding a hare, from the Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4032, back. ()

-

Fig. 51

"Mantle-Wearer," kore (?) Manisa 325, front. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 52

"Mantle-Wearer," kore (?) Manisa 325, right side. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 53

"Mantle-Wearer," kore (?) Manisa 325, back. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 54

"Mantle-Wearer," kore (?) Manisa 325, left side. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

Evidence for Sardis as a Center for Stone Sculpture

The first argument for the existence at Sardis of local sculptors' workshops in archaic and classical times is the use of local limestone (Cat. no. 9, 47, Figs. 58, 59, 60, 153, 154) and sandstone (Cat. nos. 27, 28, 29, Figs. 105-117), as well as the widespread use of what is apparently local marble. As far as scientific validation is available, judgments by both geologists and archaeologists who have handled the stones agree in describing material of the great majority of Sardian marble sculpture as local marble.167 Pieces made of imported stone are rare (serpentine and lava, cf. Cat. no. 229, Figs. 396, 397, 398, 399 and Cat. no. 16, Figs. 68, 69; marble?, Cat. no. 22, Fig. 86).

The close resemblance of technical traditions in Lydian stone sculpture and Lydian masonry work has been briefly discussed in the general introduction.168 It is particularly noticeable in the earlier pieces, especially those cut in limestone and sandstone and also in the Manisa torso (Cat. no. 8, Figs. 51, 52, 53, 54). From the mid-fifth century B.C. on, the marble technique becomes so generally unified that later reliefs and statues cannot be distinguished on technical grounds from Greek products. But until that time the use of flat chisel and drove and the use of claw-tool for background was also a means to attain a more linear effect (as in Cat. no. 8), which is distinctive for Lydian craftsmanship.

An entirely objective criterion for local provenance is the occurrence of Lydian inscriptions, which unfortunately is confined to a few stelai (Cat. nos. 17, 49, 240, 241, 242, Figs. 70, 71, 157, 419, 420, 421). Still, these provide a standard with which both the technique and style of other Lydian sculpture may be compared.

Lydian mythological subject matter does not manifest itself very clearly. Perhaps the themes most likely to be local are those in the panels of the Cybele shrine — notably the tree with goat and eagles (Cat. no. 7, panel M , Fig. 45) and the assault scene (panel R, Fig. 50), which do not have immediate Greek parallels. In other cases, local myths may be concealed under the guise of Greek iconographic types, such as the lion killer (panel O, Fig. 47) who may be not the Greek Herakles but the Lydian Tylon,169 and the charioteer who may be the original native figure behind the Greek-Lydian Pelops (panel P, Fig. 48).

Ancient authors give the impression that Lydians were fashion setters in archaic times, but only the jewelry of Aphrodite is distinctly Lydian (Cat. no. 9, Figs. 58, 59, 60); other unusual details like the pendent double belt (Cat. nos. 4, 5, Figs. 11, 12, 13, 14, 15) or upturned shoes are actually known in Greece as well. Similarly one might claim that Lydian variants of Greek motifs may be recognizable in some of the lions, and perhaps in some of the stelai (see supra Ch. II).

On the grounds of findspots, style, and technique, we can surmise that all but two of the archaic and classical pieces are of local workmanship, the two exceptions being the pieces of imported materials: the black lava stone relief (Cat. no. 16, Figs. 68, 69) and the fine leopard (?) frieze fragment (Cat. no. 22, Fig. 86).

Finally, when we consider the artistic quality of sculpture, some of the floral stelai (Cat. nos. 45, 46, Figs. 148, 149, 150, 151) are very successful. A few of the other pieces preserved attain the level of the best Eastern Greek artists: the Manisa torso (Cat. no. 8, Figs. 51, 52, 53, 54), the Cybele shrine (Cat. no. 7, Figs. 20-50), some of the lions, especially the lioness Cat. no. 34 (Figs. 125, 126, 127, 128, 129), the large lion Cat. no. 31 (Figs. 119, 120, 121, 122), and Cat. no. 24 (Figs. 90, 91), and possibly the "Persian" pediment (Cat. no. 18, Figs. 72, 73, 74). The rest of the stone sculpture is not quite of the same stature. The creators of this material may have been locally trained sculptors who worked closely with the Lydian stone masons in local workshops, concentrating on assignments and functions left aside by the great masters who worked principally in precious metals, in bronze, and in ivory. The attainments of these stone-working craftsmen were closer in quality to those of their competitors in ceramics, who mass-produced the painted terracotta reliefs and sculpture for Lydian buildings.170

-

Fig. 58

Relief of frontal standing draped female figure. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 59

Relief of frontal standing draped female figure, detail. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 60

Relief of frontal standing draped female figure, drawing. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 153

Chamber tomb stele, now lost. Plan and elevation of chamber tomb (Tomb 813) showing placement of stelai (From Sardis I (1922) ill. 178) ()

-

Fig. 154

Chamber tomb stele. ()

-

Fig. 105

Restored altar at PN with casts of lions 27 (S67.016), 28 (S67.032), and 29 (S67.033) in place, looking S. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 117

Recumbent lion on plinth, SW corner of altar, in situ. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 396

Small head of a woman (?), Private Collection. ()

-

Fig. 397

Small head of a woman (?), Private Collection, right profile. ()

-

Fig. 398

Small head of a woman (?), Private Collection, back. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 399

Small head of a woman (?), Private Collection, left profile. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 68

Two-sided relief fragment with folds or feathers. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 69

Two-sided relief fragment with folds or feathers. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 86

Fragment of Archaic relief with part of running animal. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 51

"Mantle-Wearer," kore (?) Manisa 325, front. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 52

"Mantle-Wearer," kore (?) Manisa 325, right side. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 53

"Mantle-Wearer," kore (?) Manisa 325, back. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 54

"Mantle-Wearer," kore (?) Manisa 325, left side. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 70

Inscribed stele with seated man (Atrastas, son of Sakardas), Manisa 1. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 71

Inscribed stele with seated man (Atrastas, son of Sakardas), Manisa 1, detail. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 157

Fragment with Lydian inscription. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 419

Part of sepulchral stele with palmette anthemion, Izmir Archaeological Museum 695. (top fragment only) (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 420

Anthemion with Lydian-Aramaic bilingual, stele of Manes, son of Kumlis, Izmir Archaeological Museum 691. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 421

Funerary stele with Lydian inscription and rounded palmette anthemion, stele of Alikres, son of Karos, Izmir Archaeological Museum 694. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 45

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine," Panel M. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 50

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine," Panel R. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 47

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine," Panel O. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 48

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine," Panel P. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 11

Lower part of Archaic kore, "North kore" (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 12

Lower part of Archaic kore, "North kore," side view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 13

Lower part of small Archaic kore. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 14

Lower part of small Archaic kore, side view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 15

Lower part of small Archaic kore, back view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 148

Anthemion (finial). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 149

Anthemion (finial), back. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 150

Fragment of anthemion. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 151

Fragment of anthemion, detail. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 20

Monument in the form of a shrine decorated with reliefs, with goddess standing in front, "Cybele shrine" (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 125

Lioness, Manisa 303, right side. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 126

Lioness, Manisa 303, left side. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 127

Lioness, Manisa 303, front. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 128

Lioness, Manisa 303, back. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 129

Lioness, Manisa 303, detail showing clamp holes. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 119

Large recumbent lion, left side. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 120

Large recumbent lion, right side. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 121

Large recumbent lion, front. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 122

Large recumbent lion, detail. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 90

Head and neck of lion sejant. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 91

Head and neck of lion sejant. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 72

Part of a pediment. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 73

Part of a pediment, detail of ornament. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 74

Part of a pediment, projection drawing of pediment block. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

Restoration and Reuse in Ancient Times

A striking example of conservation or restoration of statues of the Persian era in Roman times is the probable restoration of the image of the Persian Zeus Baradates of 367 B.C. and possibly others in the second century A.D., presumably caused by local patriotism and religious continuity (supra, "Literary and Epigraphic Evidence," no. 16; Cat. no. 273, Figs. 463, 464). However, we do not have the statues themselves, which may have been of bronze rather than marble.

The strangest examples of intentional reuse of Lydian-Persian sculpture are the two lion pairs found in the Synagogue flanking the "eagle table" (Cat. no. 25, Figs. 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101). Because they were placed on preexisting mosaics, they could not have been put into the position in which they were found before the second half of the fourth century A.D. A detailed discussion of their meaning for the congregation of the Synagogue must be left to the experts on Jewish religious history and the history of the Synagogue; that they did have some meaning is indisputable. One possible explanation relates them to the symbolism of the lion of Judah (Genesis 49.9), another to the existence of the Synagogue phyle of the Leontioi.171