Report 2: Sculpture from Sardis: The Finds through 1975 (1978)

by George M. A. Hanfmann and Nancy H. Ramage, with a contribution by Florence E. Whitmore

Chapter 1. The Scope of the Work and the Character of the Material

Introduction

From the beginning of the Mermnad kingdom (ca. 680 B.C.) to the fall of Croesus in 547 B.C., Sardis was the capital of the powerful and wealthy kingdom of Lydia.1 Under the Persians from 547-334 B.C., Sardis was the most important satrapal capital in the western part of the Achaemenid Empire.2 Throughout this era the native Lydian tongue was spoken. However, whether or not Lydian and Persian Sardis was an important art center with a recognizable Lydian style of its own is a problem that is yet to be solved.3 As a step toward the solution of this problem, in this report G. M. A. Hanfmann will treat together the relatively few examples of stone sculpture of the Lydian and Persian eras.

After its conquest by Alexander the Great in 334 B.C., Sardis became first a Hellenistic Greek, then a Greco-Roman, and finally a late Roman and early Byzantine city.4 Culturally and artistically, Sardis was one of the many populous cities in the Greek speaking eastern part of the Roman Empire, representative of the Hellenistic-Roman koine. Its urban and cultural development was continuous until the destruction of the city, probably by Sassanian Persians, in A.D. 616.5 N. H. Ramage has undertaken the study of this more extensive material.

Because the two groups have some problems in common and yet present a number of different aspects, some subjects are discussed in this joint introduction, while others are addressed in special introductions to each section of the catalogue (Chapters II, III, and V).

Criteria for Inclusion

The total of all sculptured pieces catalogued by the Sardis Expedition between 1958 and 1975 numbers 536. In addition, numerous fragments were marked with findspot, date, and fieldbook reference. We have included in this volume 280 pieces. Of these, 138 are from our excavations and 79 are from the category of “NoEx” (not excavated) items. This designation means that the pieces have been found by villagers and acquired by the expedition on behalf of the Archaeological Museum in Manisa or that they were found by the expedition in areas outside the excavations. A few of the NoEx pieces come from other sites in Lydia; they are listed in Chapter VIII.

This catalogue includes some of the sculpture found by H. C. Butler and T. L. Shear during the first Sardis expedition (1910-11, 1914, 1922), most of which is unpublished or only summarily published. We have discussed only those pieces that actually survive; others, of which there are photographs in the archive of the first Sardis expedition at Princeton, have disappeared and are not included.6 Several unpublished Butler pieces that were still at Sardis in 1971 are described and designated in our inventory as B-1, B-2, and so on. Other pieces found by the first Sardis expedition are in the museums of Istanbul and New York. They appear in Chapter VII, within a listing of sculpture from Sardis in European, Anatolian, and American museums, and carry numbers 232-246, 252, and 258 (Figs. 402-427, 435, 444, 445, 446). The decision to collect the sculpture from Sardis now preserved in various museums resulted from our desire to make this volume a reasonably comprehensive reflection of the output of sculpture at Sardis during the life of the ancient city. Although not complete, this collection includes a number of interesting, well preserved works. When they have been extensively published, we have repeated only the most essential information.7

Another group of material integrated into our catalogue is sculpture from Sardis found at various times, particularly between 1922 and 1958, and now preserved in the Archaeological Museum at Manisa. The pieces are numerous and their findspots are well authenticated. For this reason we have treated them together with our own finds from Sardis and have not included them in our listing of pieces kept in museums.

The catalogue begins with two or three possibly Prehistoric pieces. For the Lydian and Persian periods, we have included all fragments that offered some intelligible aspect. Stone objects without sculptural decoration, such as furnishings and vessels, will be published in other volumes in this series. For Hellenistic and Roman sculpture, our intention was to carry the catalogue through the late Roman (A.D. 280-395) period;8 but as it is difficult to draw a line between late Roman and early Byzantine sculpture,9 some pieces from the fourth and the fifth centuries have been catalogued and discussed. Sculpture of the Dark Ages (A.D. 616-800) as well as middle (800-1204) and late (1204-1453) Byzantine10 pieces will be treated in the context of Byzantine architectural and decorative sculpture.

For the Hellenistic to early Byzantine periods, we have used to some extent artistic quality as well as state of preservation as criteria for selection. In the Roman period especially, state of preservation has sometimes taken precedence over quality. Thus a well preserved, if only moderately skillful, piece has been included over scraps of what might have been masterpieces. On the other hand, even small fragments of good quality have been included if they are intelligible (for example, Cat. no. 133 Figs. 265, 266).

In the Hellenistic and Roman section, all head-capitals and other architectural members with figurative work have been included, except a few battered head-capital fragments that were previously published.11 Apart from the enigmatic classical lion-head spout in Istanbul (Cat no. 237 Figs. 410, 411, 412), lion heads on simas and other architectural pieces have been relegated to publications of architecture. A number of less important sarcophagi do not appear in the catalogue. Where historic or iconographic interests were at stake, arbitrary choices were made: thus the foot of an Imperial statue (Cat. no. 132, Fig. 264, Lucius Verus?) and the only relief with an official Imperial theme (Cat no. 191, Fig. 341, captive barbarian) are included, whereas fragments that m ay have illustrated fable or myth (water bird claw on a turtle; fragment of a leg of Pan) were omitted because they were virtually unrecognizable in photographs.

Finally, some fascinating figurative "cut-outs" of marble were among the decorative pieces found in the Synagogue.12 They will be discussed in the forthcoming volume in this series on the Synagogue.

-

Fig. 402

Relief with head of bearded man, Metropolitan Museum of Art 26.199.278 (Photograph courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Gift of The American Society for the Excavation of Sardis, 1926)

-

Fig. 427

Statue of Moschine, priestess of Artemis, Izmir Archaeological Museum 582, three-quarter view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 435

Overview. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 444

Head of a Horse, Walters Art Gallery 23.173, right profile. (Reproduced by permission of The Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore)

-

Fig. 445

Head of a Horse, Walters Art Gallery 23.173, front view. (Reproduced by permission of The Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore)

-

Fig. 446

Head of a Horse, Walters Art Gallery 23.173, left profile. (Reproduced by permission of The Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore)

-

Fig. 265

Overview. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 266

Detail of bracelet. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 410

Lion head spout: front view (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 411

Lion head spout: from right. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 412

Lion spout attached to rectangular member, drawing with elevations, top view, and section. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 264

Three-quarter view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 341

Overview. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

Previous Discoveries and Research

After his excavation of the royal cemetery at Bin Tepe in 1853, the Prussian Consul in Smyrna, H. Spiegelthal, brought a half dozen pieces of sculpture to Berlin. Among them was the so-called kouros-herm, actually a Roman work (Cat no. 249, Figs. 431, 432) and a relief of the Mother of the Gods (Cat no. 256, Fig. 442).13 The British Consul in Smyrna, George Dennis, famous for his Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria, excavated in Bin Tepe as well as in the Temple of Artemis in 1882 and brought to the British Museum two important early Lydian or Persian reliefs from Bin Tepe (Cat. nos. 230, 231, Figs. 400, 401) and a colossal head of the empress Faustina the Elder that he had found in the Artemis Temple (Cat no. 251, Fig. 434).14 Picked up by one of Dennis' visitors, a horseman relief went to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford (Cat no. 253, Fig. 436).15 A Severan portrait of a Roman lady came to Trinity College, Cambridge (Cat no. 254, Figs. 437, 438, 439, 440).16 In France, the Louvre obtained a Hellenistic marble statuette of an Eros (Cat no. 247, Fig. 428), a Hekateion (Cat no. 248, Figs. 429, 430),17 and a sarcophagus fragment of Asiatic type (Cat no. 244, Figs. 423, 424),18 and Rodin acquired for his collection a fragmentary lion head, said to be from the sima of the Artemis Temple.19 In 1893, the Glyptothek Ny Carlsberg in Copenhagen purchased a head of Augustus, which had belonged to the Swedish-Norwegian ambassador in Constantinople (Cat no. 250, Fig. 433).20

The first Sardis expedition found a number of sculptured pieces, mostly Hellenistic and Roman, many of which were reproduced in the expedition's general report, published as Sardis I in 1922; several others were described and reproduced in the volumes on the Lydian and Latin inscriptions.21 Subsequently, the first substantial discussion of Lydian sculpture was published by T. L. Shear in his article on the monument of Nannas,22 while C. R. Morey made the sarcophagus of Claudia Antonia Sabina the starting point for a pioneering monograph on the entire class of Roman Asiatic sarcophagi.23

The stone sculpture found by the first Sardis expedition was dispersed, and not all of it was published. Two pieces are in the Metropolitan Museum, New York (Cat. nos. 232, 235, Figs. 402, 405, 406); four are in The Art Museum, Princeton University (only Cat no. 259, Fig. 447 published here); one is in the Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore (Cat no. 258, Figs. 444, 445, 446); the sarcophagus of Claudia Antonia Sabina (Cat no. 243, Fig. 422), the recumbent lion, the eagle from the Nannas monument (Cat. nos. 236, 238 Figs. 407, 408, 409, 413, 414, 415), and the Menophila stele (Cat no. 245, Fig. 425) came to the Archaeological Museum, Istanbul; a few pieces are in Manisa.24 A number of pieces were left stranded in the ruin of the excavation house of the first Sardis expedition. As far as they had survived, they were rescued in 1961 by W. C. Burriss Young, then conservator of the present expedition. The colossal heads of Antoninus Pius and of Zeus (Cat. nos. 79, 102, Figs. 196, 197, 223, 224, 225) as well as the inscribed base of the Nannas monument (Cat no. 274, Figs. 465, 466) were also brought from the Artemis Precinct to the expedition camp.25

Between 1922 and 1958, a number of works were found at Sardis, both in the course of agricultural labors and during the construction of the highway (ca. 1950-1953). Some came to the museum in Izmir; others were brought to the Manisa museum, where they were listed by Vahit Armağan, then director, in a guide published in Turkish in 1946.26

The first modern survey of Lydian arts, including six examples of Lydian stone sculpture from Sardis, was H. Th. Bossert's Altanatolien in 1942.27 In 1970, K. Tuchelt devoted two pages to the archaic sculpture of Lydia in an attempt to assess the role of various regions in the development of archaic sculpture in Asia Minor, an attempt impaired by its small sample of stone sculpture.28 From 1957 on, the authors of this volume and other scholars have published a number of studies of individual pieces and sets of sculpture found at Sardis. Major sculptural finds have been regularly discussed in preliminary reports in the Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research and Dergi of the Department of Antiquities.29 Still, these efforts largely concerned scattered pieces or small groups. This volume is the first comprehensive attempt to assemble the evidence for sculptural activity at Sardis from Lydian to early Byzantine times.

The diversified but fragmentary Hellenistic, Roman, and late antique finds do not contain enough coherent, continuous, and well-preserved groups to permit an overall narration of stylistic and thematic developments beyond the observations offered in N. H. Ramage's introduction to the later sculpture. For the Lydian and Persian epochs, on the other hand, very little has been known about stone sculpture from Sardis and Lydia; our findings are new, and the pieces extant lend themselves somewhat better to an integrated stylistic overview, especially if their evidence is supplemented by references to sculpture in other media. We have, therefore, included an overview and appraisal in the introductory section on the sculpture of the Lydian and Persian periods but not in that on the Hellenistic, Roman, and early Byzantine periods.

-

Fig. 431

Double-sided herm with kouros figure on one side and herm on the other, Berlin Staatliche Museen 883. (Courtesy of the Staatliche Museen, Berlin)

-

Fig. 432

Double-sided herm with kouros figure on one side and herm on the other, Berlin Staatliche Museen 883, drawing from Berlin Beschreibung, 354, no. 883. (Reproduced from Berlin Beschreibung, 354, no. 883, courtesy of the Staatliche Museen, Berlin)

-

Fig. 442

Enthroned Mother of the Gods (Cybele), Berlin Staatliche Museen 702. (Courtesy of the Staatliche Museen, Berlin)

-

Fig. 400

Frieze from Bin Tepe with grazing deer, British Museum, B 270 (1889,1021.2). (Photograph courtesy of the British Museum.)

-

Fig. 401

Frieze of horsemen, British Museum 1889,1021.1. (Photograph courtesy of the British Museum.)

-

Fig. 434

Head of the Elder Faustina, British Museum 1936-3-10-1. Front view. (©Trustees of the British Museum)

-

Fig. 436

Horseman riding toward altar, Ashmolean Museum G1140. (Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford)

-

Fig. 437

Head of a woman, Trinity College Collection, on permanent loan to the Fitzwilliam Museum Loan 27.1969. (Courtesy of the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge)

-

Fig. 438

Head of a woman, Trinity College Collection, on permanent loan to the Fitzwilliam Museum Loan 27.1969, left profile. (Courtesy of the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge)

-

Fig. 439

Head of a woman, Trinity College Collection, on permanent loan to the Fitzwilliam Museum Loan 27.1969, back. (Courtesy of the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge)

-

Fig. 440

Head of a woman, Trinity College Collection, on permanent loan to the Fitzwilliam Museum Loan 27.1969, right profile. (Courtesy of the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge)

-

Fig. 428

Winged Eros, Louvre MA 3307. (Courtesy of Musée du Louvre, Paris)

-

Fig. 429

Triple head of Hekate, Louvre MA 3249. (Photographs by Chuzeville, courtesy of Musée du Louvre, Paris)

-

Fig. 430

Triple head of Hekate, Louvre MA 3249, detail. (Courtesy of Musée du Louvre, Paris)

-

Fig. 423

Sarcophagus fragment, Louvre MA 3199, end. (Photographs by Chuzeville, courtesy of Musée du Louvre, Paris)

-

Fig. 424

Sarcophagus fragment, Louvre MA 3199. (Photographs by Chuzeville, courtesy of Musée du Louvre, Paris)

-

Fig. 433

Head of Augustus, Ny Carlsberg Glyptothek 746. (Reproduced by permission of the Ny Carlsberg Glyptothek, Copenhagen)

-

Fig. 402

Relief with head of bearded man, Metropolitan Museum of Art 26.199.278 (Photograph courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Gift of The American Society for the Excavation of Sardis, 1926)

-

Fig. 405

Lion sejant from Nannas monument, Metropolitan Museum of Art 26.59.9, right profile. (Photograph courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Gift of The American Society for the Excavation of Sardis, 1926)

-

Fig. 406

Lion sejant from Nannas monument, Metropolitan Museum of Art 26.59.9, back. (Photograph courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Gift of The American Society for the Excavation of Sardis, 1926)

-

Fig. 447

Seated Cybele, Princeton Art Museum 29.64. (Courtesy of The Art Museum, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 444

Head of a Horse, Walters Art Gallery 23.173, right profile. (Reproduced by permission of The Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore)

-

Fig. 445

Head of a Horse, Walters Art Gallery 23.173, front view. (Reproduced by permission of The Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore)

-

Fig. 446

Head of a Horse, Walters Art Gallery 23.173, left profile. (Reproduced by permission of The Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore)

-

Fig. 422

Sarcophagus of Claudia Antonia Sabina, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4027. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

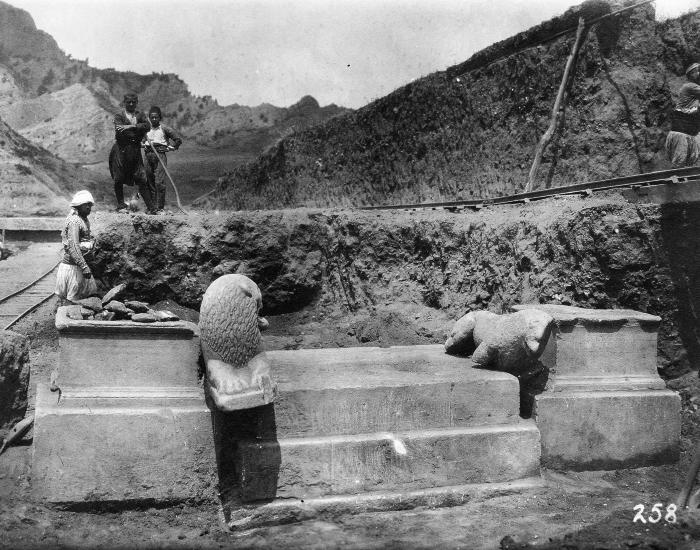

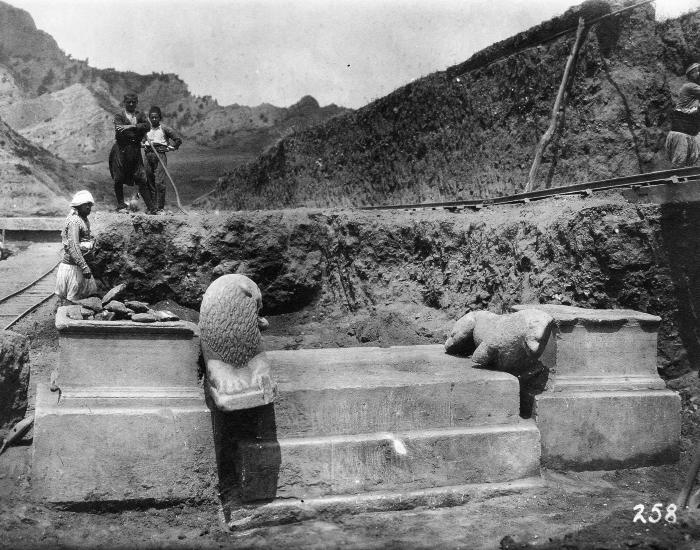

Fig. 407

Recumbent lion from Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4028, shown as excavated by the first Sardis expedtion, front. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 408

Recumbent lion from Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4028, shown as excavated by the first Sardis expedtion, back. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 409

Lion sejant and recumbent lion from Nannas monument, in situ. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 413

Bird of prey (eagle?) holding a hare, from the Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4032. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 414

Bird of prey (eagle?) holding a hare, from the Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4032, three-quarter view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 415

Bird of prey (eagle?) holding a hare, from the Nannas monument, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4032, back. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 425

Stele of Menophila, overview. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 196

Frontal view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 197

Left profile view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 223

Front view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 224

Front view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 225

Back view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

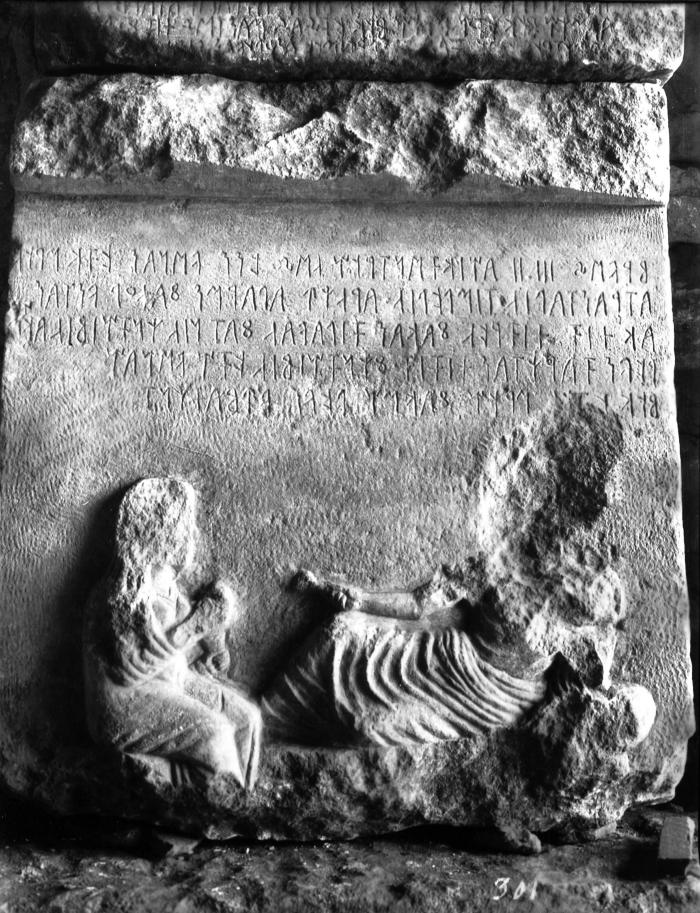

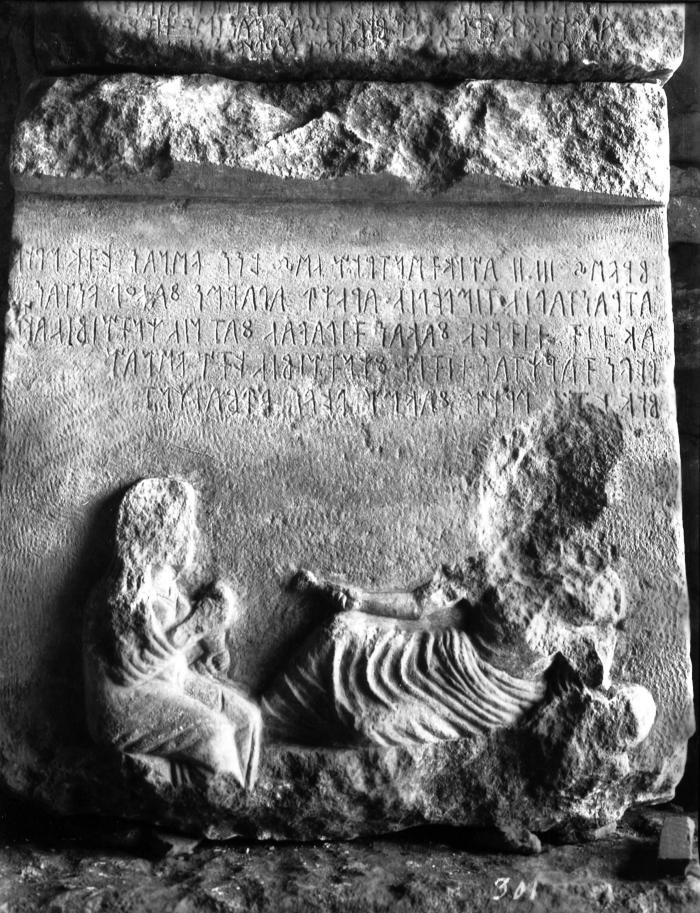

Fig. 465

Bilingual dedication of Nannas Bakivalis to Artemis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 466

Bilingual dedication of Nannas Bakivalis to Artemis, top. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

Materials

Sizable ancient marble quarries are located in a gorge known locally as Mağara Deresi, ca. 4 km. south of the Izmir-Ankara (TC 68) highway. These quarries are cut into the eastern and western flanks of the gorge made by a torrent that flows almost exactly south-north into the Pactolus. There are at least three certain quarries and one probable one on the western bank, and at least two quarries on the eastern. The general location of the quarries is shown on L. Emery's survey made in 1913. H. C. Butler suggested that the marble, still lying around in anciently quarried blocks, was used for construction of the Hellenistic-Roman Artemis Temple.30 A possibly Hellenistic relief (Cat no. 156, Figs. 301, 302, 303), is carved on a rock face of the west bank. In 1964, an attempt was made by a contractor from Manisa to reopen the quarries (quarry 2, see infra) for commercial exploitation, but the attempt was given up because the marble did not meet modern specifications.31 In 1971, Hasan Koramaz, an experienced marble worker and chief foreman of the expedition and P. A. Lins took a total of eleven samples from the west quarry and the two major east bank quarries (nos. 1, 2, and 3, respectively, see infra). They also secured sixteen samples from various pieces of sculpture. These samples were examined at the Research Laboratory of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the results of this study appear below.32

From August 27 to 29, 1972, a team of Italian geologists (D. Monna, M. Felici, and L. Pieruccini) from the Project for Auxiliary Sciences of Archaeology, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Rome, under the auspices of the Minerals Research Institute, Ankara, systematically sampled three quarries: the southernmost quarry on the western bank (designated by them no. 1); one on the eastern bank (no. 2) 200 m. north (downstream) of no. 1; and a quarry (no. 3) 200 m. south of no. 1. Some thirty samples from the quarries were collected and compared with several samples of architectural marble from the Artemis Temple and the Marble Court and with samples from several pieces of sculpture.33

According to Monna the Tmolus massif around the quarries consists of schists, marble, crystalline limestone, and volcanic (lava) stones. The direction of fracturation (quarry 2) is 208° N, similar to the direction of the gorge. Samples from various levels of quarries 1 and 2 displayed the same coarse crystals and homogeneous structure. Samples in low levels of quarry 3 had occasional gray bands.34

The marble was described as light white with coarse-grained crystals and generally homogeneous structure, with occasional orientation of crystals occurring perhaps in contact zones of marble and schist. The gray banding, too, is apt to occur at zones of contact. L. Pieruccini pointed out that at least quarry 2 was filled with ancient and modern debris to a height of several meters and noted that finer grained marble might have occurred in strata not presently accessible.

It was the opinion of the geologists, on the basis of low magnification and ocular inspection, that samples of architectural parts from the Artemis Temple35 and the Lydian bases around Altar LA 236 were of local marble. They also suggested that all four sculptured pieces of which samples were compared with the quarry samples were of local marbles. This agrees with the results obtained by F. E. Whitmore and W. J. Young at the Boston Museum Research Laboratory.37

It is our impression that the great majority of Sardian sculpture both in the Lydian-Persian era and in the Hellenistic and Roman periods was indeed made of local white to grayish marbles, but because of exposure to air, it has weathered gray. When the sculpture is buried, iron, which is present in considerable quantities in the soil, is incorporated in an accretion forming a red surface layer characteristic of much sculpture found at Sardis (according to P. A. Lins).

Another marble quarry of the Sardis region which was worked in ancient times lies at Mermere, west of the Gygean Lake. Members of the Sardis Expedition visited it and secured samples of red and white marble being worked today at the lower quarries and yellow-streaked samples from the surface of supposedly ancient quarries above the town.38

While limestone masonry seems to have preceded marble masonry in Lydian architecture by a half century,39 we have no clear evidence that a limestone phase preceded the use of marble in sculpture. The huge marker on the mound of Alyattes (580-560 B.C.)40 is of soft limestone, as is the little relief from Dede Mezari (Cat no. 9, Figs. 58, 59, 60). A crumbly sandstone is the material of the two and one half lions from the altar of Cybele (Cat. nos. 27, 28, 29, Figs. 105-117).41 Serpentine is used in the small black Prehistoric head (Cat no. 229 Figs. 396, 397, 398, 399),42 schist for the Bronze Age idol (Cat no. 1, Figs. 6, 7), and a "green stone" for the Bronze Age (?) bird (Cat no. 2 Fig. 8). The black stone used in the two-sided archaic relief Cat no. 16 (Figs. 68, 69), ca. 560 B.C., has been determined to be volcanic lava, possibly from Lydia. In the Roman period, a green marble tree (

-

Fig. 301

Rock-cut relief, aedicula with two frontal figures. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 302

Rock-cut relief, aedicula with two frontal figures, detail of goddess on r. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 303

Rock-cut relief, aedicula with two frontal figures, detail of caduceus. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 58

Frontal view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 59

Detail of face and shoulders. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 60

Draped female figure, drawing. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 105

Restored altar at PN with casts of lions 27 (S67.016), 28 (S67.032), and 29 (S67.033) in place, looking S. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 117

View in-situ. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 396

Small head of a woman (?), Private Collection. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 397

Small head of a woman (?), Private Collection, right profile. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 398

Small head of a woman (?), Private Collection, back. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 399

Small head of a woman (?), Private Collection, left profile. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 6

Lower body and feet of prehistoric idol, upper side. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 7

Lower body and feet of prehistoric idol, underside. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 8

Bird's head, left profile. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 68

Side A. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 69

Side B. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 263

Three-quarter view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

Preliminary Analysis of Marble Samples

Thirty-one thin-sections of marbles from Sardis and one thin-section of marble from Miletus were submitted to the Research Laboratory of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts for petrographic study. Remains of thirty of the above samples were also submitted in very small fragment form.

The procedures followed were: (1) The thin-sections were studied by petrographic microscope using transmitted and polarized light. (2) Where the remains of the thin-sections were supplied, the small samples were ground with an agate mortar and pestle and a slurry made on a microscope slide with collodion. The slurry was then positioned in the X-ray beam of a goniometer and an X-ray diffraction chart made at 1° per minute indicating the 2 Θ values. (3) The remainder from these ground samples was inserted in boron-free carbon electrodes, burned in a direct current arc, and spectrographic analyses made (see Table 1). (4) Photomicrographs were made by transmitted and polarized light at 10x magnification of seven samples that were analyzed by X-ray diffraction and by emission spectroscopy.

The petrographic analyses, from the study of the thin-sections, indicated that the marbles were calcite marbles with a low percentage of dolomite. except for the sample from Cat no. 88 (Fig. 201, colossus fragment, slide S.9.1971), which contained a higher percentage of dolomite.

The X-ray diffraction analyses proved all the marbles to be calcite marbles, with a small amount of dolomite present, except for the sample from Cat no. 88 (slide S.9.1971), which contained a larger amount of dolomite, thus substantiating the thin-section analyses.

When studied with the aid of a petrographic microscope, using transmitted and polarized light, it was apparent that the thin-sections of quarry samples could be separated into three groups, or as having originated from three strata of the quarry, and the object samples compared with these groups. Comparison of the crystalline structures of the marble samples in thin-section led to the results summarized in Table 2.

From the comparison of the above given analyses, it appears well within the limits of probability that the samples of objects as listed originated from the same quarry as the quarry samples, except for the three object samples which compared in thin-section with the Miletus sample.

-

Fig. 201

Overview of face fragment. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

Techniques

The techniques used by stone sculptors of the archaic Lydian and the Persian eras are related on the one hand to the stone cutting techniques used by the Lydian wall masons43 and on the other hand to the techniques of contemporary Greek sculptors.44

As in masonry,45 Lydian sculptors were strong on flat chisel and drove work. The point and flat chisel work is very clearly seen on the kore Cat no. 4 (Figs. 11, 12). A very instructive example for the different stages of tooling may be observed on the big archaic lion Cat no. 31 (Figs. 119, 120, 121, 122, ca. 550 B.C.). It shows unfinished areas as well as those done with rather large point, with flat chisel, and with claw chisel. The claw-tool, Nylander's “toothed chisel,” may have been used on the early kore Cat no. 5 (Figs. 13, 14, 15, 580-570 B.C.). It is also clearly in evidence in the finishing stage of the sides of the Atrastas stele, ca. 520 B.C. (Cat no. 17 Figs. 70, 71). Thus, it appears fairly early but not before its appearance in Greek sculpture, where its earliest use has been dated around 570 B.C.46 At Sardis, it is very widely used on sides of stelai and on sides and tops of stelai and statue bases during the fifth and fourth centuries B.C.47 Occasionally, the toothed or clawed tooling is used intentionally for the background of reliefs (Cat. nos. 233, 239, Figs. 403, 416, 417, 418), but most sculpture is well smoothed with abrasives in the finishing stage. The finest example of smoothing is the archaic relief with a running animal (Cat no. 22, Fig. 86).

In the Roman period we have a few outstanding examples to illustrate the use of special tools and finishing techniques. Many pieces were smoothed with abrasives; the clearest example is the late Roman hand with a mappa (Cat no. 133, Figs. 265, 266), where the abrasive marks were left rather than smoothed, apparently on purpose. Particularly fine examples of a high polish finish are Cat. nos. 91, 92, and 118 (Figs. 204, 205, 206, 207, 244, 245).

Some of the unfinished pieces are useful for the study of technique. A satyr (Cat no. 117, Fig. 243) still shows the marks made by the fine claw chisel, flat chisel, and the drill (upper edge of nebris); whereas the back, only minimally worked, shows the initial blocking out of the forms with flat chisel and gouge. As is so common in Roman sculpture, we have many pieces clearly finished on the front but barely worked at the back. Another satyr is a good example of this (Cat no. 118, Figs. 244, 245), where the marks of the multiple claw chisel on the front have been carefully worked over with abrasives—the final step that was missing on the other satyr—whereas the back is still quite roughly worked. Two additional examples of unfinished work are a stele (Cat no. 144, Fig. 283), where the figure is simply blocked out with large gouge marks, and a Herakles from Golde (Cat no. 266, Figs. 456, 457).48

Color and Gilding

Instances of preserved color49 among the sculpture of the Lydian-Persian era are red pigment on the maeander ornament and on the hair band of Herakles in the reliefs of the Cybele shrine (Cat no. 7 Figs. 20 - 50), and the yellow and black egg and dart on the funerary stele Cat no. 234 (Fig. 404), where red pigment was also observed in the letters of the inscription. The archaic stele Cat no. 47 (Figs. 153, 154), too, had traces of painted ornamental borders according to Butler.

Although most of the Hellenistic and Roman pieces would undoubtedly have been painted, only a few traces have survived. Some of the more noticeable examples of red are Cat no. 112 and Cat no. 188 (Figs. 238, 338) and of red and green, Cat no. 183 (Fig. 332). Especially interesting is the gilded Tyche head (Cat no. 128, Figs. 259, 260).50 Gilding of marble was apparently widely practiced in the Sardian workshops: the inscription for the dedication of the Marble Court of the Gymnasium, A.D. 211, states that “the entire work was gilded,” including presumably details of the sculptured head capitals (Cat. nos. 197-209, Figs. 349-368).51

Piecing

Apart from architectural sculpture, where piecing is to be expected (see pediment Cat no. 18, Figs. 72, 73, 74), we have an interesting early (before 550 B.C.) instance in an archaic lioness (Cat no. 34, Figs. 125, 126, 127, 128, 129) whose paw was attached with iron clamps. The clamp and dowel holes in the small Cybele relief of the fourth century B.C. (Cat no. 21, Figs. 84, 85) were intended for attaching the piece to a frame and back wall. A double-sided lion relief, ca. 580-560 B.C., has cuttings for a piece (seat or throne?) to be joined on top (Cat no. 23, Figs. 87, 88, 89). The dowels and clamps were of iron, and as far as observed, clamps were of the bridge (Pi) type.52 Among the Hellenistic statues, the colossal head of Zeus was an acrolith joined to the body by a separate vertical piece (Cat no. 102, Figs. 223, 224, 225).

Piecing was a common practice in the Roman period. We have numerous examples of bodies without heads, or sometimes arms or feet (Cat. nos. 55, 59, 67, 70, Figs. 166, 167, 168, 172, 173, 182, 185), and of heads without bodies (Cat. nos. 76, 77, 78, 91, 92, 93, 95, 254, Figs. 192-195, 204-211, 213-214, 437-440). The female statue from the House of Bronzes (Cat no. 59, Figs. 172, 173) is also notable for its unusually complicated system of dowelling in the arms so as to hide the breaks. Its missing foot, on the contrary, shows no evidence of dowelling. A simpler arm dowel can be seen on the draped female Cat no. 57 (Fig. 170) and the cuirassed fragment Cat no. 72 (Fig. 188). Examples of piecing in the middle of the body are the skirted Amazon (Cat no. 112, Fig. 238), the Herakles torso (Cat no. 114, Fig. 240), and the palliatus (Cat no. 69, Fig. 184).

Additional information on technical matters as well as on the original function, display, reuse, and repair of the sculpture from Sardis is given in the introductory essays on the sculpture of the Lydian and Persian periods and that of the Hellenistic, Roman, and early Byzantine (late antique) periods.

-

Fig. 11

Front view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 12

Side view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 119

Large recumbent lion, frontal view, left side. Set up at find spot near Synagogue. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 120

Back view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 121

Side view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 122

Detail of mane. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 13

Front view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 14

Side view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 15

Back view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 70

Inscribed stele with seated man (Atrastas, son of Sakardas), Manisa 1. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 71

Inscribed stele with seated man (Atrastas, son of Sakardas), Manisa 1, detail. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 403

Stele with praying woman, overview. Butler photo. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 416

Sphinx, presumably part of a throne or seat, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4031, left profile. (Courtesy of the Archaeological Museum, Istanbul)

-

Fig. 417

Sphinx, presumably part of a throne or seat, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4031, right profile. (Courtesy of the Archaeological Museum, Istanbul)

-

Fig. 418

Sphinx, presumably part of a throne or seat, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4031, front. (Courtesy of the Archaeological Museum, Istanbul)

-

Fig. 86

Fragment of Archaic relief with part of running animal. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 265

Overview. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 266

Detail of bracelet. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 204

Overview of fragments. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 205

Frontal view of face. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 206

Three-quarter view of face. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 207

Right profile view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 244

Frontal view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 245

Detail of clasp at shoulder. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 243

Frontal view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 283

Overview. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 456

Frontal view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 457

Back view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 20

Overview from top right (BW) (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 50

Panel featuring man. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 404

Funerary stele of Atrastas, son of Timles, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4030 (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 153

Chamber tomb stele, now lost. Plan and elevation of chamber tomb showing placement of stelai (From Sardis I (1922) ill. 178) (Reproduced from Sardis I (1922) ills. 178 and 122, respectively)

-

Fig. 154

Anthemion stele in situ in Tomb 813. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 238

Frontal view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 338

Overview. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 332

Overview. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 259

Left profile view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 260

Three-quarter view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 349

Overview. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 368

Detail of eyes. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 72

Frontal view of pediment. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 73

Detail of bead and reel design. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 74

Section of a pediment, projection drawing. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 125

Lioness, Manisa 303, right side. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 126

Lioness, Manisa 303, left side. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 127

Lioness, Manisa 303, front. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 128

Lioness, Manisa 303, back. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 129

Lioness, Manisa 303, detail showing clamp holes. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 84

Frontal view of relief. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 85

Three quarter view of relief. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 87

Left side view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 88

Right side view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 89

Overview. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 223

Front view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 224

Front view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 225

Back view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 166

Woman with archaistic drapery, Manisa 385. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 167

Woman with archaistic drapery, Manisa 385, 3/4 view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 168

Woman with archaistic drapery, Manisa 385, detail. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 172

Frontal view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 173

Right profile view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 182

Palliatus (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 185

Palliatus torso, frontal view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 192

Frontal view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 195

Portrait of Sabina (?), Manisa 3, left profile. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 211

Detail of crown. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 213

Frontal view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 214

Right profile view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 437

Head of a woman, Trinity College Collection, on permanent loan to the Fitzwilliam Museum Loan 27.1969. (Courtesy of the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge)

-

Fig. 440

Head of a woman, Trinity College Collection, on permanent loan to the Fitzwilliam Museum Loan 27.1969, right profile. (Courtesy of the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge)

-

Fig. 170

Frontal view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 188

Front, three-quarter view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 240

Frontal view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 184

Fragment of palliatus. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

Notes

- 1See Pedley, passim, and for the ancient sources Sardis M2, nos. 39-139.

- 2Sardis M2, nos. 140-191.

- 3Lydian tongue: Sardis M3, 51-55, with chronological chart showing the range from the 7th to the 3rd C. B.C. All inscriptions with royal dates are of the 4th C. B.C.; see Gusmani, LW, 17-19. For Sardis as an art center see Boardman, Pyramidal Seals, 39. Boardman has proved, on the basis of Lydian inscriptions, that certain groups of seals with Persian and Greek motifs must have been made at Sardis. For attributions of pottery to Sardis workshops see C. H. Greenewalt, Jr. CSCA 4 (1971), 165 and n. 36, doubtful on "Early Fikellura"; CSCA 5 1972, 128-236, fish skyphoi, bowl, lydions, jewelry; CSCA 6 (1973), 119-121, "Ephesian Ware" doubtful; idem in Hanfmann Studies, 46-48, terracotta figure vase. Terracotta friezes: Åkerström, Terrakotten Kleinasiens, 67-96; BASOR 215, 54-58. Preliminary discussions of sculpture, Hanfmann, Rayonnement, 493-498; Hanfmann, "Pediment", 299-301. For Lydian architectural terracottas, see SardisM5.

- 4Sardis M2, nos. 192-210 and nos. 211-232; Sardis M4 passim. The chronological terminology in our volume follows approximately that presented in Sardis R1, 6, where "late Roman" is defined as A.D. 280-395, and "early Byzantine" is 395-616. C. Foss advocates calling the period from A.D. 284-616 "late antique," Sardis M4, 2ff. Writers on the history of art, however, tend to use the term "early Byzantine" for the 5th and 6th C. arts within the Byzantine Empire. We should perhaps recall that for numismatists “Byzantine” coinages begin with A.D. 491 (Anastasius I), as in Sardis M1, 1.

- 5Sardis M1, 1-3; Sardis R1, 32-33, n. 136; Sardis M4, 53ff. Doubts were expressed by P. Charanis, “A Note on Byzantine Coin Finds in Sardis,” Epet 39-40 (1972-73), 175-180, about attributing the destruction to Sassanian attack; no historical source reports the destruction of Sardis by Chosroes II. The date of the destruction, however, is cogently attested by numismatic evidence.

- 6See "Previous Discoveries and Research," infra. We are much indebted to R. Stillwell for permission to recheck (in 1972) the photographic archive at Princeton and for making available a copy of the list of negatives and photographs.

- 7For example, the sarcophagus of Claudia Antonia Sabina, Sardis V, here No. 243 (Fig. 422); several portraits by Inan-Rosenbaum and others; and a horse head in Shear, “Horse” and Hill, passim, here 258 (Figs. 444-446).

- 8Cf. n. 4, supra, and for the culture of the period at Sardis, Sardis R1, 29-32 and Sardis M4, Ch. 1.

- 9See Hanfmann, "Late Portraits," 290-295, on the difficulties of dating, and N. H. Ramage, Ch. V, infra.

- 10See Sardis R1, 6 for chart of site chronology.

- 11Hirschland (i.e., Nancy Hirschland Ramage), nos. 5, 10, 13, 14.

- 12BASOR 170, 45; Hanfmann, Letters, 169, fig. 130; Seager, Synagogue, 7, fig. 22.

- 13Berlin Beschreibung, nos. 702, 883.

- 14Pryce, 99-101, B 269-270, figs. 164-165. Faustina, Inan-Rosenbaum, no. 41.

- 15Sardis VII (1932), 98, no. 96a, fig. 85.

- 16JHS Archaeological Reports (1970-71), 81, no. 11, fig. 6 (Fitzwilliam Museum).

- 17Eros: Charbonneaux, SGR, 81, no. 3307. Hekateion: L. Robert, Hellenica 10 (1955), 155, n. 3.

- 18Sarcophagus: E. Michon, MelRome (1906), 83, fig. 3; Sardis V (1924), 39, ill. 60 ("Sardis A").

- 19Musée Rodin, Rodin Collectionneur (Paris 1967-68), no. 144, pl. 51 (Inv. 53).

- 20Ex-Collection Selim d'Ehrenhoff, Istanbul: V. H. Poulsen, Portraits, no. 33, pls. 50-51.

- 21Sardis I (1922), ills. 2, 47, 49, 57, 58, 61, 86, 96, 98, 99, 122, 137, 138, 151-153, 164, 172-173, 179, 180; Sardis II (1925), figs. 91-93; Sardis VI.2 (1924), no. 1, pl. 1; no. 3, pl. 2; no. 8, pl. 4; no. 17, pl. 7; no. 20, pl. 8; no. 26, pl. 11 (Lydian); Sardis VII (1932), figs. 20, 22, 85, 86, 89, 100-101, 141, 153, 204 (Hellenistic and Roman).

- 22Shear, "Lion"; cf. Cat no. 274 (Figs. 465, 466).

- 23Sardis V (1924), esp. 3-17; cf. Cat no. 243 (Fig. 422).

- 24See Ch. VII and the index under the respective museums. An animated discussion was provoked by the horse head in Baltimore, the only piece of those hidden by the expedition in 1914 that has appeared in a museum (Shear, "Horse"; Hill, passim). For the sarcophagus of Claudia Antonia Sabina and its transfer to Istanbul, see Mansel, "Erwerbungsbericht," passim. Menophila: Sardis VII (1932), 108, figs. 100-101. For Manisa see Hanfmann-Polatkan, "Sculptures".

- 25BASOR 166, 34-35. The Nannas base was moved to the Sardis camp in 1968.

- 26Armağan, passim. Cf. also the lioness Cat no. 34 (Figs. 125, 126, 127, 128, 129). For pieces in Izmir, see Ch. VII, Cat. nos. 233, 240, 241, 242, 260 (Figs. 403, 419, 420, 421, 448, 449); also A. Dönmez, Sart Kilavuzu (Istanbul 1956) and Aziz, fig. 9, for strigil sarcophagus relief. Mansel, Perge, 49, fig. 29, sarcophagus lid, inv. 883; same in Rodenwaldt, 201, fig. 13.

- 27Bossert, Altanatolien, figs. 166-167, British Museum; 192, Izmir; 193, Istanbul; 195, Manisa. Perrot-Chipiez, 9, fig. 535, reproduced the horsemen relief from BT in the British Museum. E. Akurgal's fine account of Lydian arts in Kunst Anat included only the two reliefs in the British Museum.

- 28Tuchelt, 185f.; see also 155f. Six pieces of stone sculpture from Sardis are included as nos. L 42 bis, 73 b-c, 105, 111, in his "Liste der Plastik archaischer Zeit aus Kleinasien," 124, 126, 128-129.

- 29The regular preliminary reports of the Sardis Expedition to 1971 are listed in Hanfmann, Letters, 346; see 347-348 for major publications on specialized subjects. The book also contains a considerable number of illustrations of sculpture found before 1971. Aspects not treated in detail in this volume are dealt with by Gabelmann (lions); Inan-Rosenbaum (portraits); Hirschland (capitals); Hanfmann-Waldbaum, "Kybele"; Hanfmann, Rayonnement; Hanfmann, “Lydian Relations with Ionia and Persia,” Xth Congress of Classical Archaeology (forthcoming); Hanfmann, Croesus; Hanfmann, "Late Portraits", 288-295; Hanfmann, "Pediment" (Persian period); Ferrari, 39-40 (sarcophagi); H. Wiegartz in Mansel Melanges, 376; Wiegartz, Saulensarkophage, 48; N. H. Ramage, "Draped Herm from Sardis," HSCP 78 (1974) 253ff.

- 30Sardis I (1922), 19, pl. 1; Sardis R1, 17, 21.

- 31Hanfmann, Letters, 149.

- 32We are indebted to F. E. Whitmore and W. J. Young for their generous cooperation.

- 33D. Monna kindly permitted G. M. A. Hanfmann to take notes on his informal, tentative comments, which are published at the latter's responsibility (with Monna's permission). According to a letter from D. Monna (June 13, 1975), work on the samples taken at Sardis was postponed indefinitely because of lack of funds. The rather inconclusive preliminary results of chemical (trace element) and isotopic (carbon and oxygen) analyses obtained by the Italian mission for five other Western Anatolian quarries (Marmara, Afyon, Denizli, Aphrodisias, and Ephesus) are published in Conforto et al., passim, and Manfra-Masi-Turi, passim. We owe the reference to P. A. Lins and J. A. Scott. See also Campbell, 171, 257, 495-500, 506.

- 34Dimensions of quarries in m.: no. 1: W. N-S 40; D. E-W 16; H. 35. No. 2: W. N-S 13; D. E-W 22; H. 11. No. 3: W. N-S 40; D. E-W (open face) 3; H. 40.

- 35Column drum from Artemis Temple, Ionic shaft, perhaps Hellenistic, fragment excavated by K. J. Frazer in trench 2, Sardis R1, 82. Part of marble tile, same location. All compared well to samples from quarries 1 and 3. According to D. Monna, samples from a plain second-story column, entablature, and base of the screen colonnade of the Marble Court at Building B (Figs. 347, 348) might also be of local marble. On the other hand, J. B. Ward-Perkins, with sample in hand, invokes the authority of F. Rakob to classify the large spirally fluted columns of the Marble Court gate and three other columns as coming from the African quarries at Chemtou, marmor numidicum (by letter, March 5, 1970). He notes that African marble is known from an inscription to have been imported to Smyrna.

- 36NSB and SSB, Sardis R1, 68-73. Concerning the stele with the Timarchos inscription of 155 B.C., Sardis I (1922), 128, fig. 140; Sardis VII (1932), 10-12, no. 4; Sardis R1, 60, 68, fig. 75, the opinion was that the marble looked less coarse than the quarry samples but might yet come from finer-grained local deposits. The geologist D. A. Young, New York University, noted on preliminary examination that the marble had very few mineral inclusions, that it displayed two or three different directions of twinning, and that there was some distortion and deformation. According to Young the samples displayed reasonably high-grade metamorphosis, and he feels that those from the various pieces of sculpture might well be from the same marble as the quarry samples.

- 37Cat no. 13 (Fig. 65) part of draped (Persian-Oriental?) figure, Cat no. 79 (Figs. 196, 197) head of Antoninus Pius, Cat no. 102 (Figs. 223, 224, 225) head of Zeus, Cat no. 201 (Fig. 356) satyr capital from screen colonnade of the Marble Court. For the results obtained by Whitmore, see infra (she did not examine Cat no. 201).

- 38For location of Mermere, see C. Foss in Sardis R1 (1975), 19, 20, 23, 24, fig. 2. The Mermere quarry was studied in 1975 by N. Asgari; see AfA 80 (1976), 284. We owe the report on the quarries and the samples to C. Foss and J. A. Scott, who visited the quarries in 1974.

- 39Limestone wall in the presumed mound of Gyges, BT 63.1, should date before 645 B.C., death of Gyges: BASOR177, 31-35, figs. 30-33; BASOR 182, 27-29, figs. 21, 22, 24. Other limestone and sandstone examples: masonry of palace (?) terraces on the Acropolis; the so-called Pyramid Tomb; and the archaic altar of Artemis. BASOR 206, 15-20, figs. 5-7; 166, 28-30, fig. 24; Sardis R1 (1975), 90, 92, figs. 183-191. The only identified and datable archaic marble masonry is in the chamber of the mound of Alyattes, ca. 580-560 B.C., BASOR 170, 55, fig. 41.

- 40H. Spiegelthal in J. F. M. Olfers, "Über die lydischen Königsgräber bei Sardes und den Grabhügel des Alyattes..." AbhBerl (1858), 539-556, pl. 3:1-2; BASOR 170, 52, nn. 56-57; Hanfmann, "Prehistoric Sardis", 161. The Alyattes and other phallic markers will be treated in a separate article by G. M. A. Hanfmann.

- 41Determination made by P. A. Lins, Sardis 1975.

- 42Determination by C. Frondel, Harvard University, 1975.

- 43They will be treated in detail in the forthcoming publications on BT. Cf. BASOR 177, 33-34, figs. 31-32; BASOR 182, 27-29, figs. 22, 24. Sardis R1 (1975), 73, 92-94; and the note on "Lydia," Nylander, 51: "various types of points and flat chisels, perhaps also edged hammers, curved chisels, and droves...rasps and abrasives." In this excellent chapter on masonry technique he rightly points out (ibid., 49) that the problems of stoneworking are essentially the same everywhere and it is “the entire set-up” within the different traditions which makes the distinctions. For tools, cf. also ibid., fig. 14.

- 44Richter, Gravestones, 4-6, figs. 181-190. Blumel, Sculptors, 6-32, esp. fig. 16. Adam, 3-83, part 1 on tools.

- 45Nylander, 51 and 54, n.124. Cf. BASOR 177, 33-34, fig. 33, for a typical example. Sardis R1 (1975), 68-73, 78, 92-94, 98, and index s.v. Masonry and Tooling.

- 46Nylander, 54, n.123, cites Athens, Acropolis Museum kore 593, as the earliest example, "generally dated 580-570 B.C."

- 47Sardis R1 (1975), 67-73, figs. 104-114.

- 48See also Sardis I (1922), 53, ill. 48, unfinished and "severely weathered." It appears to have been lost.

- 49Reutersward, 35-45, 65-66, 74-82, discusses the use of red paint in archaic marble sculpture.

- 50For the use of gold on marble, see Reutersward, 143-168, 184-186, 195-201, 203, 210, 247, and the "Venus in Bikini," Pompeii Reg. 11:11, 66, found in 1954. Pompeii (Exhib. 1973, Haag) no. 99 and color plate.

- 51BASOR 177, 25. Hanfmann, Croesus, 52. The inscription will be published by L. Robert.

- 52Cat no. 34 (Figs. 125, 126, 127, 128, 129). For the various types of masonry clamps see Nylander, 65-67.

-

Fig. 465

Bilingual dedication of Nannas Bakivalis to Artemis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 466

Bilingual dedication of Nannas Bakivalis to Artemis, top. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 422

Sarcophagus of Claudia Antonia Sabina, Istanbul Archaeological Museum 4027. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 125

Lioness, Manisa 303, right side. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 126

Lioness, Manisa 303, left side. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 127

Lioness, Manisa 303, front. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 128

Lioness, Manisa 303, back. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 129

Lioness, Manisa 303, detail showing clamp holes. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 403

Stele with praying woman, overview. Butler photo. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 419

Part of sepulchral stele with palmette anthemion, Izmir Archaeological Museum 695. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 420

Anthemion with Lydian-Aramaic bilingual, stele of Manes, son of Kumlis, Izmir Archaeological Museum 691. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 421

Funerary stele with Lydian inscription and rounded palmette anthemion, stele of Alikres, son of Karos, Izmir Archaeological Museum 694. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 448

Lid of sarcophagus of "Pamphylian" type, Izmir Archaeological Museum 833, three-quarter view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 449

Lid of sarcophagus of "Pamphylian" type, Izmir Archaeological Museum 833, end view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 347

The Gymnasium: the "Marble Court" as restored by the Harvard-Cornell Expedition, showing originals or casts of head capitals 198-206 in place on the screen colonnade. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 348

Screen colonnade, Fig. 347, showing originals or casts of head capitals in place. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 65

Overview of shoulder fragment. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 196

Frontal view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 197

Left profile view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 223

Front view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 224

Front view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 225

Back view. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 356

Overview. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)