Conservation at Sardis (2020)

by The Sardis Conservation Team

Site Preservation

Site Preservation: Introduction

Site preservation at Sardis aims to care for the many extant architectural monuments from throughout the city’s long history. Several of these figure prominently in the areas of the site that are open to visitors, and so are under increased pressure. These structures require regular maintenance and assessment of condition to ensure their continued survival in the current environment and their legibility in the archaeological landscape. Among the more extensive site conservation projects carried out over the last 60 years are the reconstruction of the Bath-Gymnasium complex and Synagogue in the 1960s and 1970s (videos 1, 2, Fig. 3); a roof over Roman and Lydian houses in sector MMS, built in 1996 (Figs. 4, 5); the reconstruction of the Lydian Altar (2010-2012, below), and the cleaning of (or, more properly, removing the biofilm from) the Temple of Artemis (2014-2018, below).1 Among the projects currently underway are the “Touristic Enhancement Project” (TEP), which aims to roof and protect the mudbrick Lydian Fortification in sector MMS and the Synagogue across the modern road.

-

Fig. 1

Video of the construction of the Marble Court, 1967. (Film by Charles Lyman.)

-

Fig. 2

Video of lifting mosaics of the Synagogue, 1967. (Film by Charles Lyman.)

-

Fig. 3

Conservator Larry Majewski working on the reinstallation of panels of the mosaic floor in the Synagogue in 1973. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 4

Newly constructed polycarbonate and steel shelter protecting Roman and Lydian houses at sector MMS (the “Touristic Enhancement Project”). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 5

Protective shelter roof over Roman house with painted walls, overlying a Lydian house with mudbrick walls, in 2002 after restoration of a new Roman floor. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

Cleaning the Temple of Artemis

One of the most beautiful Greek temples in the world is the Temple of Artemis at Sardis (video fig. 6). Begun in the generations after Alexander the Great, construction continued on and off for some 700 years without ever completing the building. Like other prestigious buildings of Greco-Roman antiquity, it was built almost entirely of marble, extracted from local quarries about 4 km away. In the Roman period even the roof was made of marble, and the building gleamed brilliantly in the afternoon sun, before the backdrop of the red cliffs of the Acropolis.

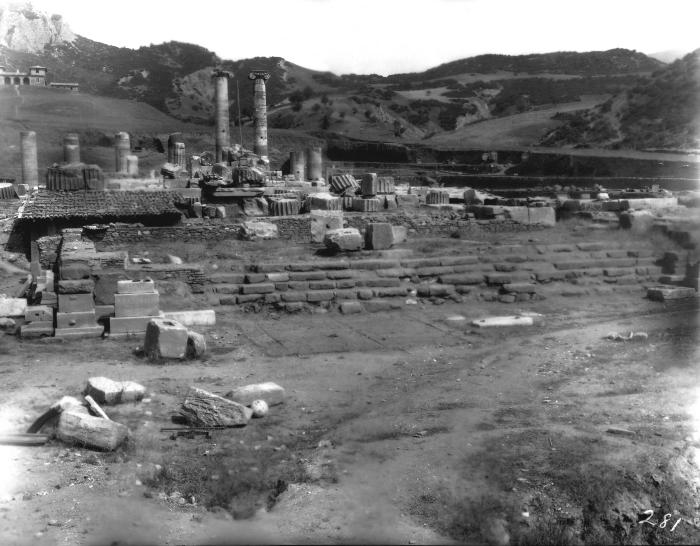

The temple was excavated by Howard Crosby Butler between 1910 and 1914 (Figs. 7, 8). The building we see today is essentially in the state Butler found it: it has never undergone extensive restoration, and the two standing columns have stood since antiquity, the only survivors of about a dozen that were actually raised.

In the century since Butler’s excavation, however, exposure to the environment of the modern world led to the unchecked growth of black cyanobacteria and lichen over the surface of the temple blocks, covering the white marble with a tenacious biological film (Figs. 9, 10). In addition to looking unsightly, these microbes ingest the surface and cause permanent damage, and also provide a “blackboard” for foolish visitors to scratch their names.

In 2012 conservator Michael Morris suggested a new method for removing this damaging biofilm using a gentle biocide, Preventol. In addition to killing the active biological material, Preventol has a prophylactic effect that deters new biological activity for years. After several seasons of tests and experiments (Figs. 11, 12, 13), Morris and Hiroko Kariya developed a protocol and in 2014 began a five-year project funded by a generous grant from the J. M. Kaplan Fund.

The conservators trained a team of local women—the first instance of women working on a field project at Sardis—to carry out the treatment. The team worked from west to east, starting at the lower, less well preserved part of the temple and gradually revealing the original glow of the marble (video fig. 14, Figs. 15, 16, video fig. 17, 18, video fig. 19). They also revealed or clarified aspects of the temple’s construction, such as the delicate workmanship of the Northwest Stairs, the presence of lead sheets between two courses of the cella walls, and the Lydian inscription on one of the Hellenistic pedestalled columns (Figs. 20, 21).

The completion of the Artemis Temple cleaning project is a tremendous achievement for the expedition as a whole as well as the site conservation team (Figs. 22, 23). The cleaned temple stands as a testament to the importance of continued care and maintenance for archaeological features, from the smallest coin to the largest monument. Even a few years later it is difficult to remember how dark and discolored the building was; we therefore left the top of one of the columns uncleaned as a reminder (Fig. 24).

-

Fig. 6

Video: the Temple of Artemis during cleaning of one of the standing columns, 2017. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

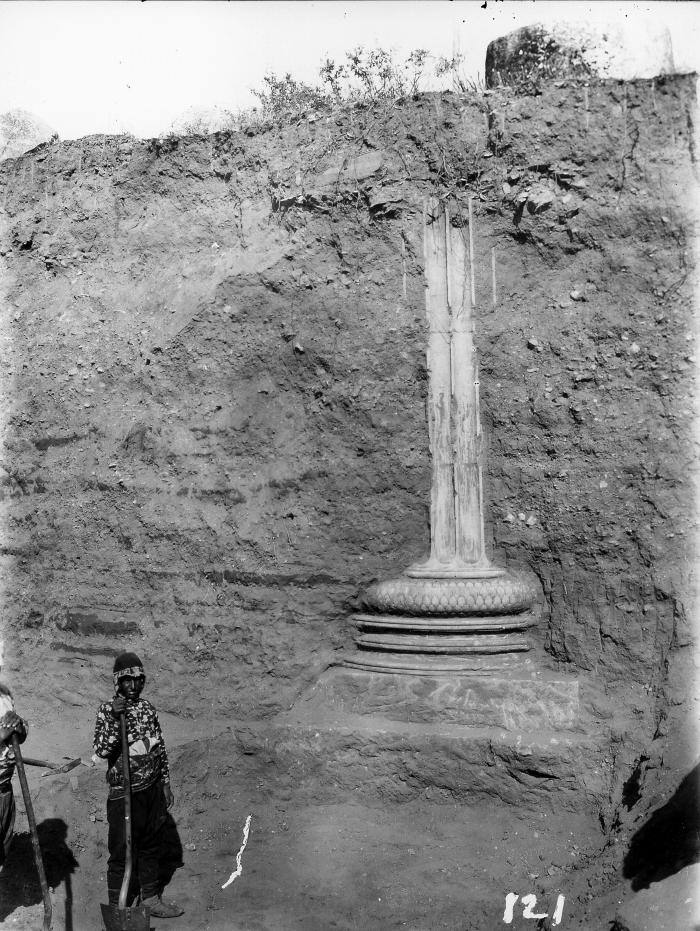

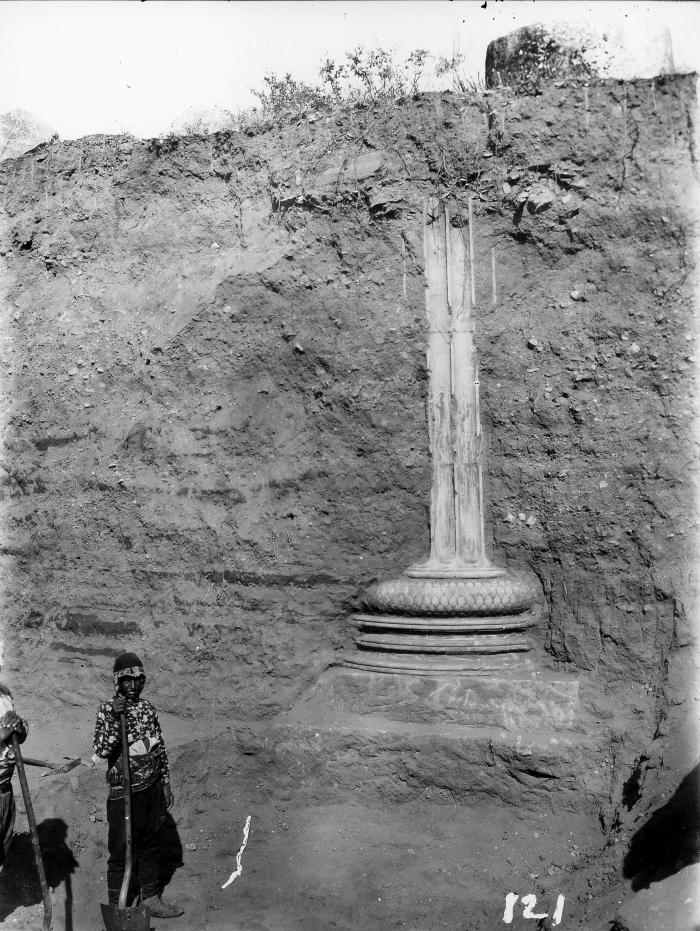

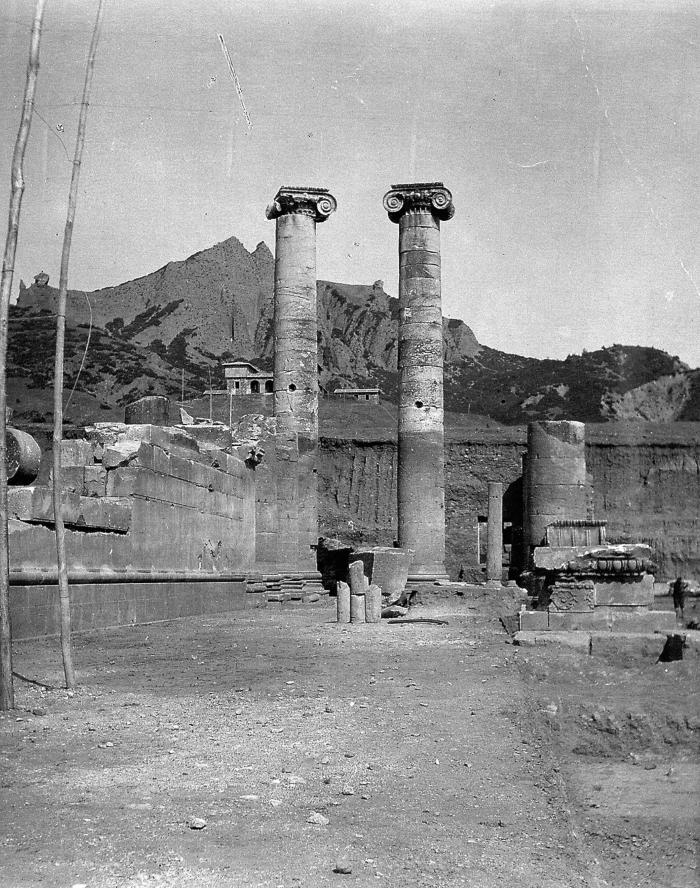

Fig. 7

Butler’s excavation of one of the pedestalled columns of the temple of Artemis, 1911. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

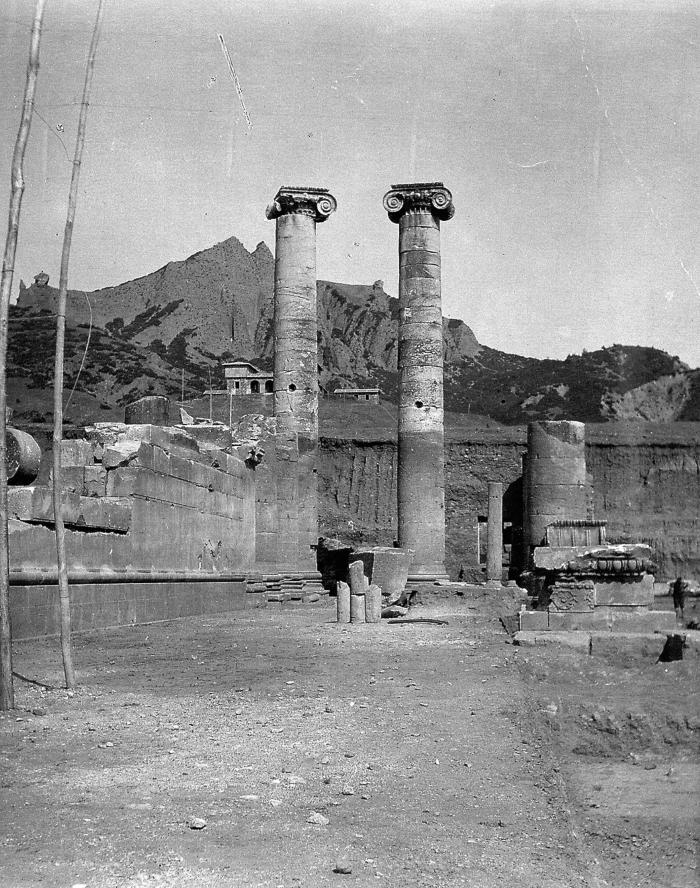

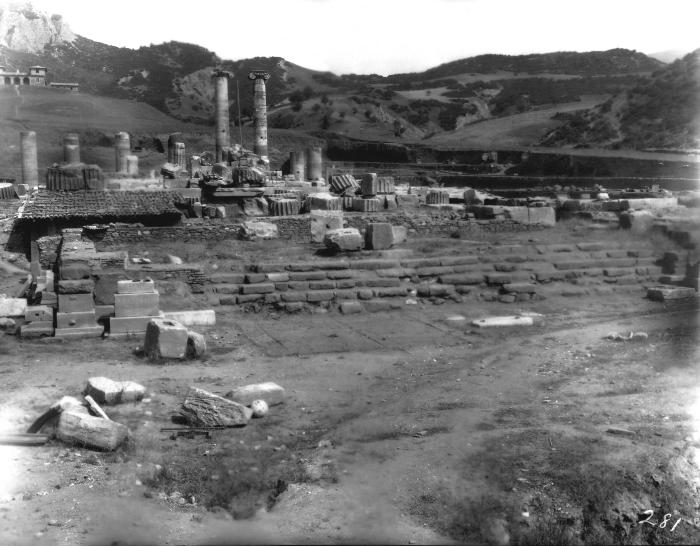

Fig. 8

Butler’s excavation of the south wall and columns of the temple of Artemis, 1911. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 9

North wall and northeast anta of the temple, 1911. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 10

North wall of the temple, 2013, showing cyanobacteria and lichen. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 11

Michael Morris and Hiroko Kariya testing the new method of cleaning marble using Preventol, on the wall of Building Q in the sanctuary of Artemis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 12

The north wall of the temple of Artemis, discolored by a century of lichen and cyanobacteria, with Hiroko Kariya testing the new method of cleaning marble using Preventol, 2013. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 13

Hiroko Kariya testing the new method of cleaning marble on the north wall of the temple, 2013. The overhanging block resting on the protected surface beneath from rain, preserving the original surface of the marble. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 14

Video: cleaning the north wall of the temple, 2014. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 15

Cleaning the south wall of the temple, with Michael Morris, Teoman Yalçınkaya, and Hiroko Kariya, 2016. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 16

South wall after cleaning. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 17

Video: cleaning one of the pedestalled columns (column 12). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 18

Cleaning one of the pedestalled columns (column 12). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 19

Video: cleaning one of the standing columns. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 20

Lydian inscription on column 12 before cleaning. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 21

Lydian inscription on column 12 after cleaning. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 22

Temple of Artemis before cleaning. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 23

Temple of Artemis after cleaning. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 24

Column 8, deliberately left partly uncleaned. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

The Lydian Altar

The Altar of Artemis (“Lydian Altar”), one of the oldest preserved buildings in the precinct of the Temple of Artemis, was discovered in 1910 by the Butler expedition (Fig. 25).2 The existing elements of the structure, including the foundations and the few marble blocks forming the stairs, bear evidence of reuse and reconstruction in antiquity as an earlier building (LA1) was incorporated into a later expanded structure (LA2). After the efforts during the 2006 and 2007 seasons to excavate and clean the Altar further (Fig. 26), the expedition team realized a conservation project to conserve and restore the extant architectural elements. Between 2010 and 2012, with the support of the J.M. Kaplan Fund, the altar was restored. Blocks of the earlier LA1, which had been removed, apparently in 1920 in order to explore under the building, were reset in their original locations (Fig. 27, 28, 29). Fifty-five soft, deteriorating sandstone blocks of the stair foundations and nine blocks of the perimeter wall of LA2 were consolidated with tetraethoxysilane, and some were further treated with diluted acrylic resin (Fig. 30). Because the sandstone cannot endure foot traffic of visitors, we decided to protect them with travertine blocks, recreating the original marble stairs that were robbed in antiquity (Fig. 31). The walls were stabilized and capped with slate, to restore the structure as much as possible to the state in which it was found in 1910 (Fig. 32).

-

Fig. 25

View of the Lydian Altar during excavation in 1910. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 26

Lydian Altar in 2007 after cleaning and excavation, showing displaced sandstone foundations of stairs. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 27

Lydian Altar in 2006 showing gap where blocks were removed from early structure LA1. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 28

Resetting displaced blocks from the early altar LA1, 2010. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 29

Resetting displaced blocks from the early altar LA1, 2010. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 30

Hiroko Kariya consolidating the sandstone blocks of LA2 with tetraethoxysilane. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 31

Travertine stairs built to protect the original sandstone foundations, partly constructed. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 32

Lydian Altar after restoration, with Brianna Bricker and Hiroko Kariya. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

Notes

- 1On the reconstruction of the Bath-Gymnasium Complex, see Mehmet Bolgil, “The Reconstruction of the Marble Court and Adjacent Areas,” in Yegül, Sardis R3, 152-168.

- 2Cahill and Greenewalt 2016, 488.