The Temple of Artemis

History and Ground Plan

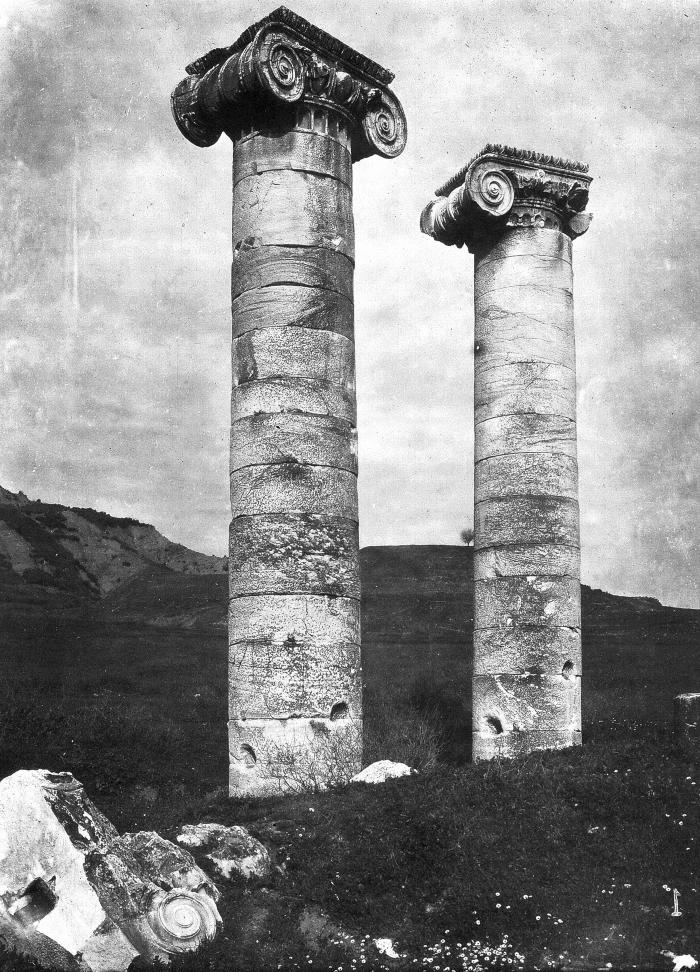

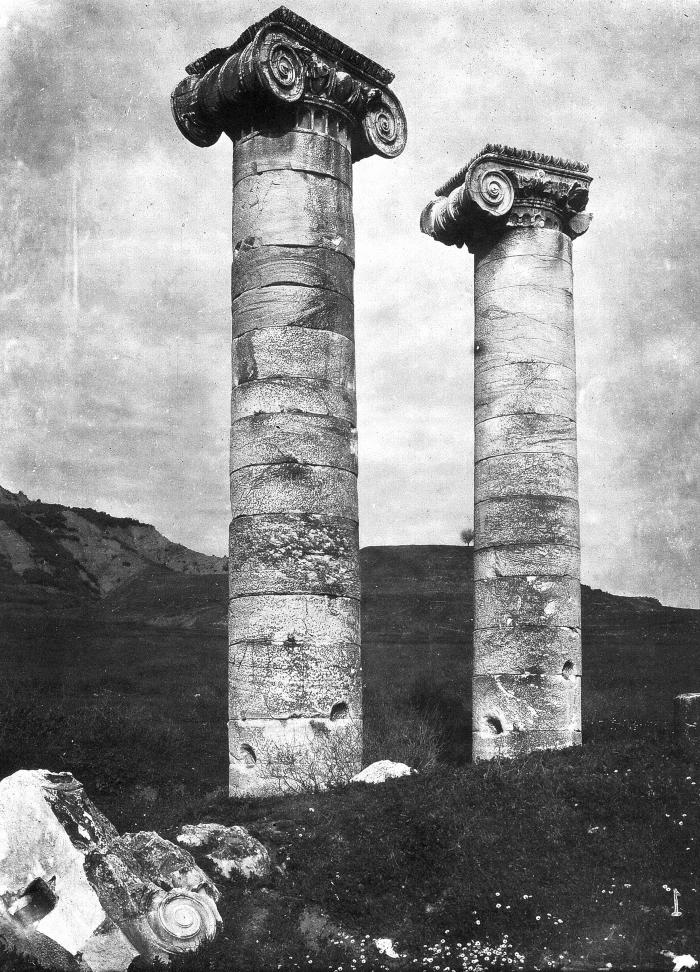

This temple, one of the largest in the world, was originally dedicated to Artemis. It faced west like other Anatolian temples of Artemis such as those at Ephesus and Magnesia (figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10; see also drone videos in Wings over Sardis). The two complete columns have stood intact since antiquity and have never been restored (fig. 11).

The Artemis worshipped at Sardis was probably not the familiar Greek goddess of the hunt, but was related to Artemis of Ephesus, a native Anatolian deity. In the Roman period, Artemis was joined in the temple by the Roman emperors, as half of the temple was walled off and dedicated to the imperial cult. The columns were added at this time and stood ever since. In late antiquity it was partly converted to a Christian church, and it is still visited by tours of the faithful.

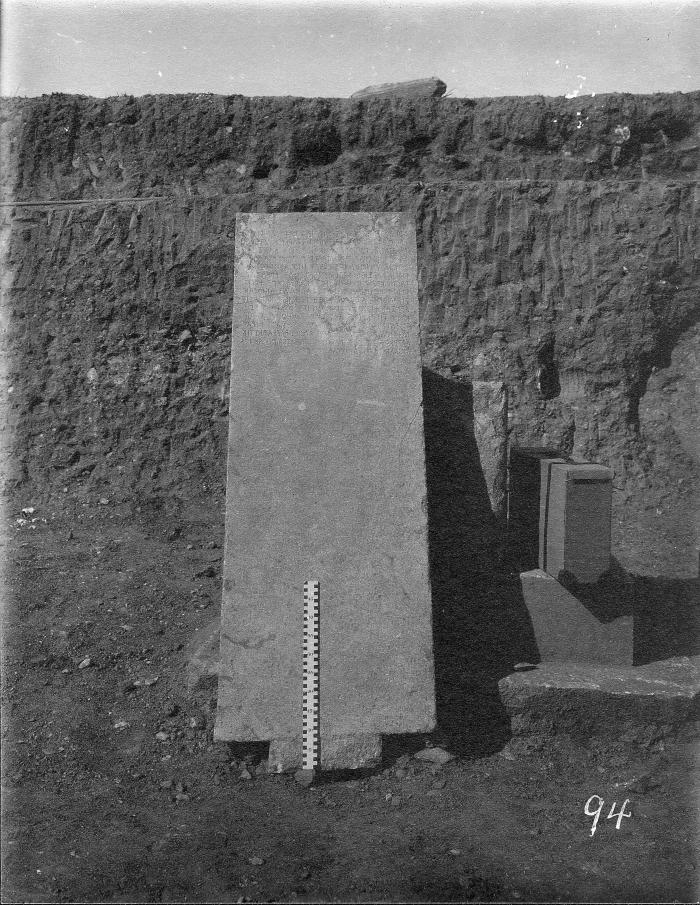

Persian Era (547 - 334 BC): No trace of a temple of the Persian era remains, but a sanctuary of Artemis existed here (fig. 12). Inscriptions in the Lydian language mentioning the cult of Artemis and other remains dating to this era were found in the sanctuary (fig. 13). The oldest preserved monument in the sanctuary is probably the early altar, which dates from the late sixth or fifth century BC (figs. 12, 14) (see The Altar of Artemis).

Hellenistic Era (334 BC - 17 AD): The temple was begun during the Hellenistic era, in the third century BC. Only the main building (cella) was built during this period (figs. 12, 15). Its roof was supported by two rows of interior columns. The columns around the outside of the building must have been planned but were not begun.

Roman Era (17 - 400 AD): In Roman times (first or second century AD) the cella was divided into two equal parts by building a cross wall, and a new doorway was cut through the east wall to create two back-to-back chambers (figs. 16, 17, 18). This was perhaps done in order to accommodate the cult of the Imperial family as well as that of Artemis. The interior columns may have been removed, and 8.5 m high statues of the the Roman emperors and their wives were set in the cella (figs. 19, 20, 21).

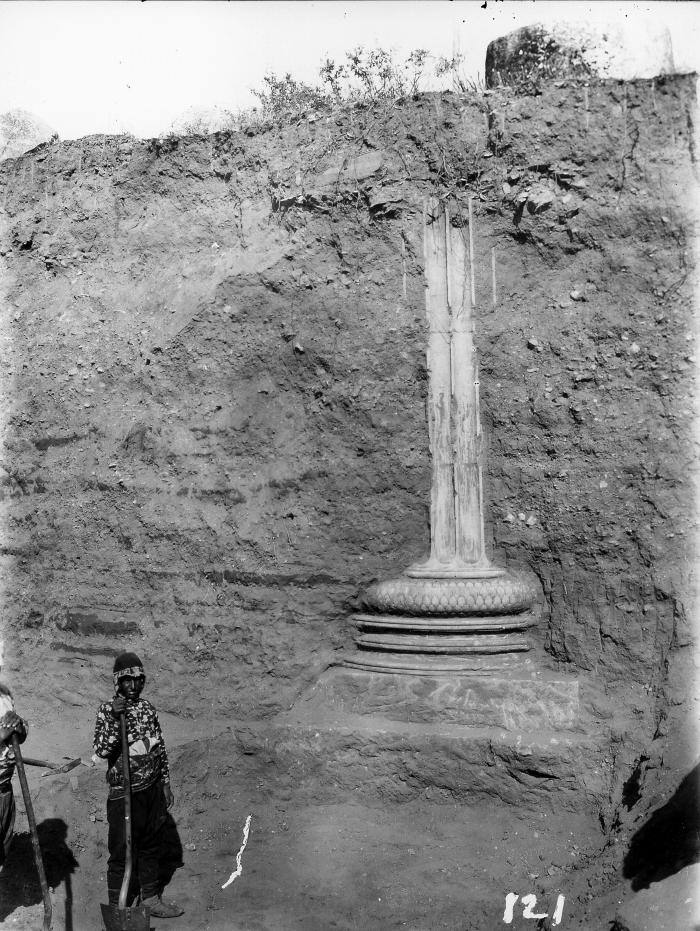

Probably at the same time, the exterior colonnade was begun on the east (the original back of the temple; fig. 6). The columns at the east end of the temple were erected but never finished. On the long north and south sides the foundations were laid, and on the west, none of the columns were even begun. The four fluted columns elevated on pedestals, two at each end, were probably those removed from the Hellenistic cella. Because these columns were somewhat shorter than other exterior columns, they required pedestals to attain the same height (fig. 22).

Late Roman and Byzantine Eras (400 - 700 AD): The decline of the cult of Artemis is poorly understood. The official recognition of Christianity in the fourth century AD led to the closure of pagan sanctuaries, but the building probably remained in use. The small church at the east end was built in the fifth century AD (figs. 6, 12, 23; see Church M), and crosses and Christian slogans (“light”; “life”) were incised on the east doorway of the temple (fig. 24). From the seventh century onwards, the building fell into disrepair, and many of its stones were reused or burned for lime.

After limited excavation in 1750, 1882, and 1904, the temple was fully exposed between 1910 and 1914 by the Howard Crosby Butler expedition (figs. 25, 26).

-

Fig. 1

Plan of Sardis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 2

Aerial view of the Temple of Artemis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 3

Overhead view of the Temple of Artemis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 4

View of the Temple of Artemis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 5

View of the Temple of Artemis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 6

View of the Temple of Artemis, looking west. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 7

East porch of the Temple of Artemis, with Brianna Bricker and Bahadır Yıldırım. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 8

State Plan of the Temple of Artemis, by Fikret Yegül. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 9

Plan of the Temple of Artemis, by H.C. Butler with additions from excavations 2002-2012. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 10

Composite restored plan of the Temple of Artemis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 11

View before excavation showing standing columns. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 12

Phase plan of the Temple of Artemis, according to Cahill. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

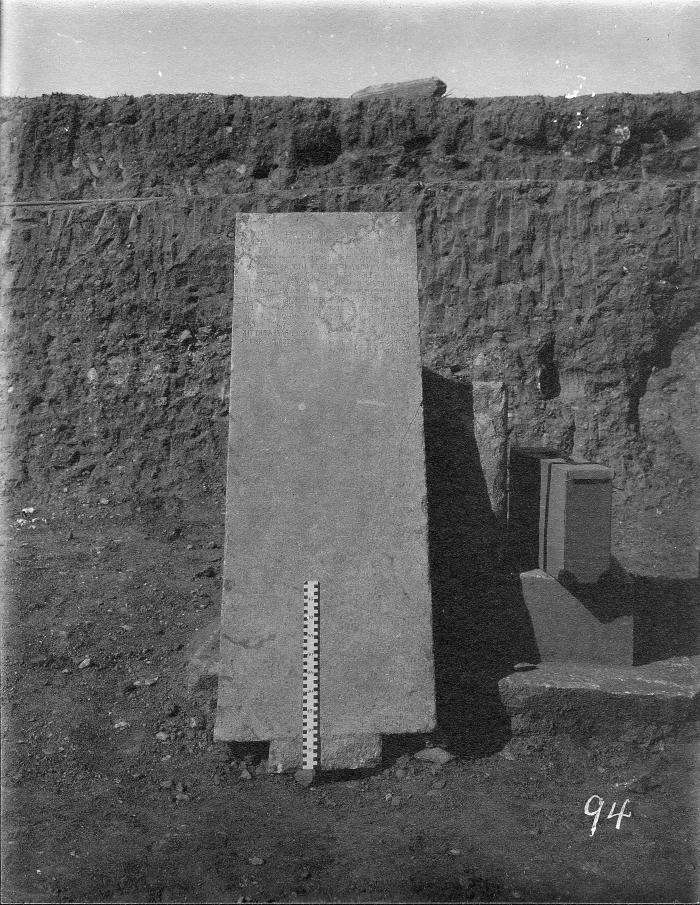

Fig. 13

Lydian stele in situ in North Stele Bases of sanctuary of Artemis (now in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv. 26.59.7). (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 14

View of Lydian Altar and Temple of Artemis, 2007 (before restoration). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 15

Restored plan of Hellenistic phase of the Temple of Artemis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 16

Plan showing hypothetical state of completion of Roman phase of the Temple of Artemis (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 17

Hypothetical fully restored plan of Roman phase of the Temple of Artemis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 18

Reconstruction of fully restored Roman phase of the Temple of Artemis, view from southeast, by Fikret Yegül. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 19

Head of Commodus as found buried in the east porch. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 20

Head of Commodus from a late Roman pit in the east porch. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 21

Reconstruction of Commodus as a standing, cuirassed figure. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 22

Elevated column in east porch, with Crawford H. Greenewalt, jr. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 23

View of Church M. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 24

Christian graffiti on east door of the Temple of Artemis. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

Fig. 25

The temple of Artemis before excavation, 1910. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

-

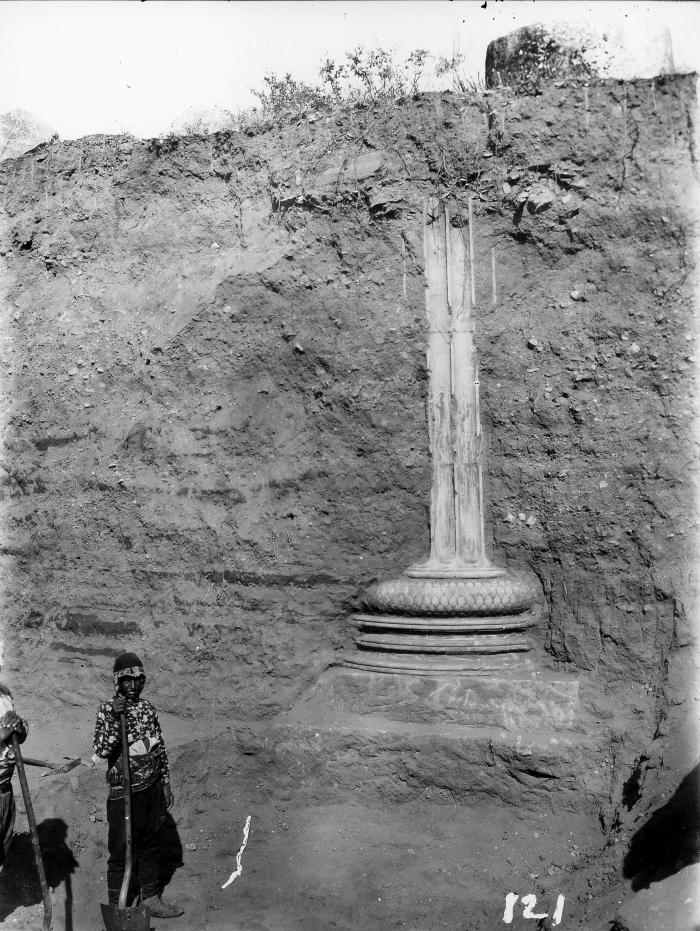

Fig. 26

Excavation of one of the elevated porch columns (#11) by H.C. Butler, 1911. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

How Was It Built?

Although it was used for more than 800 years, the temple of Artemis was never completed, and the unfinished parts of the building give a misleading impression. For instance, the only finished columns are those on high pedestals at the east end. Their slender proportions, crisp definition, and rhythmical forms show how the other, roughly finished and unfluted columns would have looked if they had been completed. But these unfinished parts of the building reveal how the masons designed the temple, worked the stone, and lifted blocks into place. In addition, different building techniques help to date different parts of the temple to the Hellenistic or Roman periods. The perfection of the design and construction of the temple of Artemis attests the high professional commitment of its ancient builders, and is an inspiration to all who visit the temple today.

Quarrying: The marble for the temple comes from quarries located 3 km to the south (figs. 27, 28). Blocks were transported in a roughly worked state to protect the surfaces from damage, and only finished once they were set in place. Natural imperfections in the marble were cut out and filled with carefully cut plugs or “dutchmen.”

Lifting: One method of lifting heavy blocks is the “lewis,” a wedge-shaped iron key fit into a flaring cutting in the center of the block (figs. 29, 30). Such cuttings are found in Hellenistic column capitals and many Roman blocks. The largest complete block that survives is the Roman beam (architrave) that originally rested on the two standing columns; it weighs 23.2 tons and was lifted 18 meters high to the tops of the two standing columns using a specially built crane (fig. 31).

Shifting: Once lifted into position, blocks were moved into position with crowbars, using pry holes cut in the block below for leverage (figs. 32, 33).

Joining: Blocks were bonded without mortar by means of clamps (to join adjacent blocks) and dowels (to join blocks set upon one another). Hellenistic clamps and dowels were made of iron and encased in lead; the lead prevented the iron from rusting (figs. 34, 35, 36, 37). Many Roman clamp cuttings do not contain insets for iron bars, nor are iron or lead clamps found in the cuttings; these clamps may have been made of wood (fig. 38). Most Roman blocks do not bear dowel cuttings, but the column drums were dowelled with bronze and lead dowels.

Finishing: During construction, joining surfaces of blocks were trimmed with fine chisels and abrasives until they were as smooth as glass and the joints all but invisible. Run your finger along the lower surface of a block on the long north wall which has been shifted by an earthquake to appreciate the expertise and care paid by the ancient craftsmen. The exterior surfaces, however, were not worked until the entire building was complete. Only narrow strips were trimmed in order to align the blocks, and short sections beneath the column capitals were carved to guide later fluting. Three inscriptions on parts of columns that would have been cut away — a lifting boss and the rough skin — read “ΜΕϹΚΕΑϹ”, probably meaning “trim me,” the column speaking to remind the workmen to finish their work (figs. 39, 40).

-

Fig. 27

Map of Sardis area showing the Mağara Deresi quarries (#6). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 28

View of Quarry in the Mağara Deresi. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 29

Clamp and lewis holes in the Roman cross-wall of the Temple of Artemis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 30

Philip Stinson demonstrating modern iron lewis keys inserted in a Roman lewis hole in crosswall of the Temple of Artemis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 31

Architrave block, originally spanning columns 6 and 7. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 32

Hellenistic clamp cuttings, dowel cuttings, and pry holes in north wall of the temple. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 33

Philip Stinson demonstrating modern pry bar inserted in ancient pry hole in the north wall of the cella. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 34

Drawing of junction of Hellenistic north cella wall with Roman crosswall showing clamps, dowels, and pry holes (Fikret Yegül). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 35

Hellenistic clamps in foundation of cella columns. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 36

Hellenistic clamp and dowel cuttings in cella column foundations. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 37

Diagram of Hellenistic clamps and dowels. (Drawing by Crawford H. Greenewalt, jr.)

-

Fig. 38

Roman clamp hole in north-south cross wall. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 39

Column 17, with inscription on plinth and dutchman repair. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 40

Inscription on column 17 reading ΜΕΣΚΕΑΣ, “trim me”? (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

Design and Ornament

Like the Parthenon in Athens and other prestigious Greek buildings, the Artemis Temple contains slight deviations from horizontality and verticality, which were introduced for aesthetic reasons. The Temple had a hemispherical curvature (rising from the four corners to the center) like that of a small rectangle on the surface of a large sphere. The curve of the long side of the Artemis Temple, if continued, would form a huge circle with a diameter of perhaps 14-18 km. The profiles of column shafts have - in addition to an upward taper - a continuous swelling (entasis), measurable in finished shafts and evidently calculated in unfinished ones, which contribute a springy “life” to the shafts, implying their response to the weight of ceiling and roof that they support.

Ornament on column bases and capitals exemplifies the precision and crispness of definition, the tensile line quality, and the rhythms of repetition and contrast (broad and narrow, curved and pointed, convex and concave, etc.) that give Greek art its special appeal (fig. 41).

Column capitals: Some volute “eyes” had appliqué ornaments (rosettes ?) of bronze; as is attested by sockets, some of which contain bronze stems; on a few plain volute “eyes” lightly incised lines may belong to graphic calculations for the volute spiral (figs. 42, 43, 44).

Column bases are the so-called Asiatic Ionic type, consisting of torus and scotia members. Only those on the high pedestals are completely finished, as these are Hellenistic bases reused from elsewhere in the building (figs. 45, 46, 47). Finished and partly-finished torus members are carved with braid (guilloche) and overlapping leaf (imbrication) patterns; which were common decorative motifs and probably had no symbolic meaning (figs. 46, 47). On column 6, oak leaves are carved with acorns and small creatures (e.g., salamander, scorpion, snail) (figs. 48, 49). On column 4, the leaf pattern belongs to a wreath, with leaves diverging from a ribbon at the back (west) and converging on an appliqué star or rosette, attested by attachment socket holes, at the front (east) (fig. 50). An inscription encircles the column (below).

High pedestals of unusual design supported two columns at the east end (and two columns at the west end, no longer standing, were supported on similar pedestals; fig. 22). The pedestal course that has a slightly outflaring profile and roughly trimmed surface may have been intended for carved decoration (that course is partly composed of cut-down column drums, flute channels of which may be recognized at several corners). The columns supported by those pedestals evidently belonged to the Hellenistic building, and were moved to the porches in Roman times from their original location, probably inside the Temple.

-

Fig. 41

Drawing of a Hellenistic capital and base from the Temple of Artemis. (From H.C. Butler, Sardis I)

-

Fig. 42

Hellenistic capital from the Temple of Artemis, with Bahadır Yıldırım. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 43

Roman capitals in situ on the east columns of the Temple of Artemis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 44

Roman capital in situ showing cutting for bronze ornament, and ancient repair insert. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 45

Hellenistic column base 10, on Roman pedestal. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 46

Base of unfinished Roman column 5. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 47

Base of unfinished Roman column 13. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 48

Base of unfinished Roman column 6, with oak leaves and creatures. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 49

Base of unfinished Roman column 6, with oak leaves and creatures (detail). (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 50

Base of unfinished Roman column 4, with wreath and inscription. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 22

Elevated column in east porch, with Crawford H. Greenewalt, jr. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

Inscriptions on the Temple of Artemis

Inscriptions on the temple offer additional dimensions to understanding this unique building. The walls of Greek temples were often used as “notice boards” for public documents. A long text in Greek inscribed on the inside of the north wall concerns a loan of 1325 gold staters from the sanctuary to a man named Mnesimachus (fig. 51; Buckler and Robinson 1932, no. 1). The inscription lists his collateral assets, including property, and provides important evidence for the role of ancient sanctuaries as banks, and information about the topographical features of Sardis and the indigenous names of those features.

A short Greek verse rings the bottom of a column at the east side of the temple (fig. 52). Some letters are missing and the meaning of some words is obscure. W. H. Buckler and D. M. Robinson’s translation (slightly modified) is “My torus and my foundation-block are each a single stone, and of all [the columns] I am the first to rise, [built] of entire stones not furnished by the people but given by friends” (Buckler and Robinson 1932, no. 181).

Two short, incomplete texts in the Lydian language are inscribed on lower ends of Hellenistic columns mounted on pedestals in the porches of the temple (the latter fragment is now in the Manisa Museum). One reads “[M]anes ? son of Bakivas ...” (Buckler 1924, no. 21); the other reads “(so-and-so), son/daughter of Srkastús, of S(ardis ...” (see LATW No. 37; figs. 53, 54). They probably name the donors of those columns, a tradition attested at other sites including the temple of Artemis at Ephesus, whose columns were dedicated by King Croesus of Sardis.

In the 4th-5th centuries AD, terms with Christian significance, “light” (ΦΩΣ) and “life” (ΖΩΗ), were carved on the south jamb of the door (fig. 24). Like crosses incised on both door jambs and on the south wall of the porch, they were “doubtless intended to banish the demons of paganism” (Buckler and Robinson).

-

Fig. 51

Inscription recording the loan of 1325 gold staters to Mnesimachos. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 52

Inscription on column 4. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 53

Lydian inscription on elevated column 11. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 54

Lydian inscription from the Temple of Artemis. (©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College)

-

Fig. 24

Christian graffiti on east door of the Temple of Artemis. (Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

Further Reading

Butler, Sardis I (1922); Butler, Sardis II: The Architecture, Part 1: the Temple of Artemis (1925); Gruben, “Beobachtungen zum Artemis-Tempel von Sardis”; Yegül, “The Temple of Artemis at Sardis” (2012); Yegül, “A Victor's Message: The Talking Column of the Temple of Artemis at Sardis”; Cahill and Greenewalt, “The Sanctuary of Artemis at Sardis: Preliminary Report, 2002-2012”; Yegül, Temple of Artemis, Sardis Report 7 (2020)

.